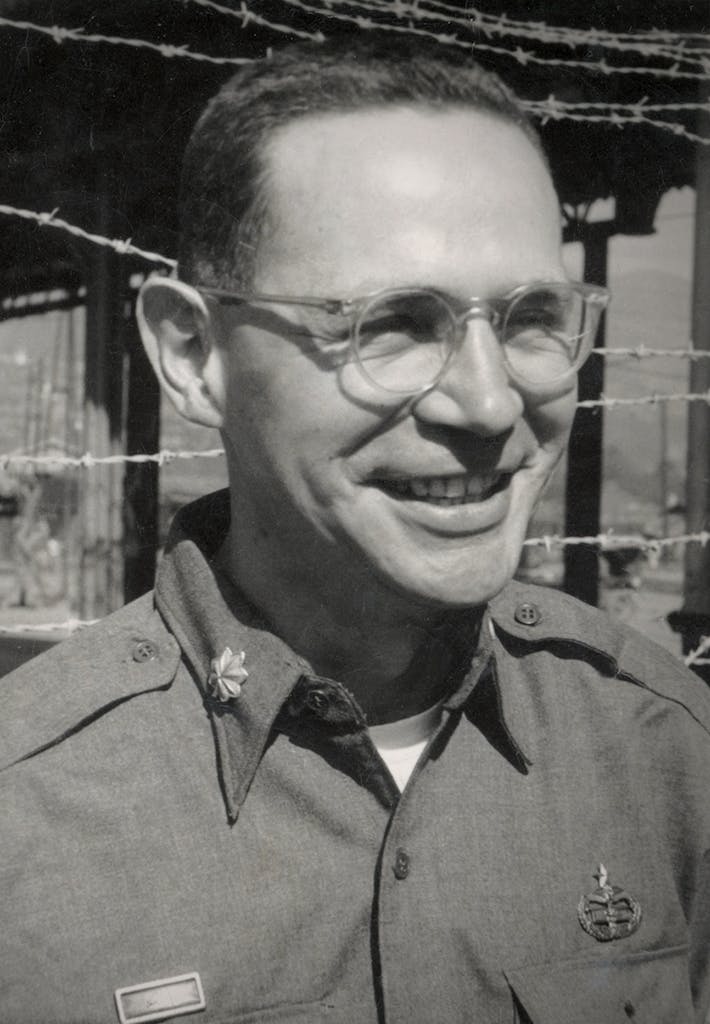

Dwight Angell had one last mission to fly before heading home on R&R to see his young wife. A 24-year-old Navy ensign, he was the navigator on a Neptune patrol plane that left Japan on the morning of January 18, 1953, headed south toward the China coast. Around 1 p.m., enemy forces attacked the Neptune, and the pilot ditched in the cold, choppy waters between China and Taiwan. Eleven men waited for four hours in and around a life raft, until a U.S. Coast Guard rescue plane arrived and they were brought on board. But the aircraft faltered as it took off: an engine cut out and a surging swell smashed into the plane. By the time a destroyer showed up, hours later, more than half the plane’s passengers were missing. Angell was one of them.

His wife, Gerry, was in Denver at the time, staying with her mom. Gerry adored Dwight. They had met in college at Colorado A&M University and later eloped, ending up in Hawaii, where he had to report for duty. He flew to Japan, and she—after getting diagnosed with polio—returned to Denver. On January 20, 1953, the day after her twenty-second birthday, she received a telegram from the U.S. Navy: Her husband had been missing for two days.

Gerry, who had recently suffered a miscarriage, was devastated. While the Navy would later speculate that Dwight was “possibly” being held in a communist prison, he was never found. Gerry eventually remarried, but even after giving birth to two daughters, she longed to know what had happened to her first love, the man with arching eyebrows and a broad smile who had disappeared in the war.

“My mom spent the rest of her life looking for him,” Megan Marx, one of her daughters, told me. Gerry called her representatives in Congress and worked with various veterans’ groups, trying to locate Angell’s remains. After Gerry died, in 1999, Marx and her sister, Lisa Brooks, continued the search. They dragged out Gerry’s old trunk, full of letters, newspaper clippings, and photos, and organized its contents. They sought anything they could find about the war. They dove into the internet, which was still relatively new. It was daunting work. Nobody, it seemed, knew anything about casualties from Korea, long called the Forgotten War.

In 2005 a fellow war researcher told Marx that she should check out a website called the Korean War Project. When she found it, she couldn’t believe her eyes. The site, run by two brothers named Ted and Hal Barker, functioned as a massive archive and digital community center for veterans of the war and their families, stocked with millions of pages of documents, photos, battle reports, maps, diaries, letters, and official government papers. What’s more, Angell had his own page, and there was a link to a web story published by an aviation history site about the crash and the rescue attempts. The website provided details about Angell—his hometown, his unit, the final struggle off the coast of Shantou, China. None of this was new to Marx, but she was just happy to see him treated like a human being—a hero, even.

Marx contacted the Barkers and sent them a photo of the smiling Angell, which they posted at the top of his page along with remembrances Marx had written. The project also told families how to provide DNA samples to the Department of Defense, to help identify the remains of unknown troops buried in Honolulu, and Angell’s twin brother, Otis, sent one.

Sixteen years later, in 2021, Hal Barker conveyed a piece of unpleasant news. As Marx was aware, a new Wall of Remembrance was planned for the Korean War Veterans Memorial, in Washington, D.C., a granite half circle that would be etched with the names of 36,634 dead Americans, plus another 7,174 Koreans who served under U.S. command. Hal explained that the wall, which opens to the public July 27, wouldn’t include Angell’s name, nor those of the others who died that day off the coast of China—or even those of hundreds more sailors, soldiers, airmen, and Marines who were not considered official casualties of war. In addition, according to Hal, the monument would likely contain more than a thousand spelling errors.

Marx was dumbstruck. “It’s so infuriating,” she said. “He sacrificed his life for his country. He believed in that.” It was as if Angell were being ghosted by his own government.

The Korean War Project, managed by the Barker brothers out of a two-bedroom apartment in the White Rock Lake area of North Dallas, exists because of the reticence of one veteran, namely their father. Marine Lieutenant Colonel Edward L. Barker was like a lot of veterans that way. Ted and Hal would ask him about battles he’d fought and the medals he wore on special occasions—especially the Silver Star, which they knew was the third-highest medal for valor. “None of your goddamn business,” he would tell Hal. Barker was a hard dad—intense and verbally abusive, like Bull Meechum, the antihero of Pat Conroy’s novel The Great Santini. His reluctance to speak about the conflict would become the driving mystery of their lives.

The Barker brothers weren’t the only ones uninformed about Korea. The Forgotten War has never received the attention given World War II or Vietnam. In truth, it wasn’t even called a war at the outset—it began as a United Nations “police action,” set in motion after North Korea, aided by the U.S.S.R. and China, invaded South Korea on June 25, 1950. The UN forces, led by the U.S., fought back, and the conflict raged for three years. Although an armistice was signed on July 27, 1953, the war was never officially declared over. Some five million civilians and members of the military on both sides died in Korea, including more than 36,000 Americans. Maybe because the conflict had ended in such an undramatic way, it faded into the recesses of national memory. The veterans who survived, like those who made it through other wars, rarely talked about their experiences. Meanwhile, around eight thousand missing Korean War troops—about a quarter of the total dead—remain unaccounted for.

Hal Barker never lost his curiosity about his father’s past. While Ted, the older of the two, joined the Marines, Hal worked as a photojournalist in Raleigh, North Carolina, got his degree in history, married, traveled through North Africa, and wound up in Boulder, Colorado, in 1977, working as a carpenter. It was while he was living there that Hal went behind his father’s back and wrote the commandant of the Marine Corps, General Robert H. Barrow: What had his father done to earn the Silver Star?

A Marine Corps historian wrote back. Barker had been a helicopter pilot, and at one point during a bloody, month-long battle known as Heartbreak Ridge, he had made three separate attempts to rescue a downed pilot named Arthur Donald DeLacy, of Chicago. Under heavy fire from the enemy, Barker was unable to rescue DeLacy, who was likely taken as a prisoner and was never seen again.

Stunned by the story, Hal set out to learn more. He attended a 1982 reunion of the Twenty-third Infantry Regiment, some of whose members had fought at Heartbreak Ridge, and asked whether they remembered a helicopter rescue attempt. Not only did they remember, they said they’d never seen anything like it. They could recall hearing the bullets hit the helicopter and seeing pieces of the fuselage fly off. They remembered the pilot coming back again and again from behind a ridgeline, trying in vain to rescue the downed Marine. “He kept flying in, flying in,” said one, still amazed almost thirty years later. “Everybody was cheering,” said another.

Finally, Hal spoke. “That’s my dad,” he said.

Forty years later, Hal still gets choked up at the memory. “I realized there was more to the story,” he told me. “My dad was just the beginning.”

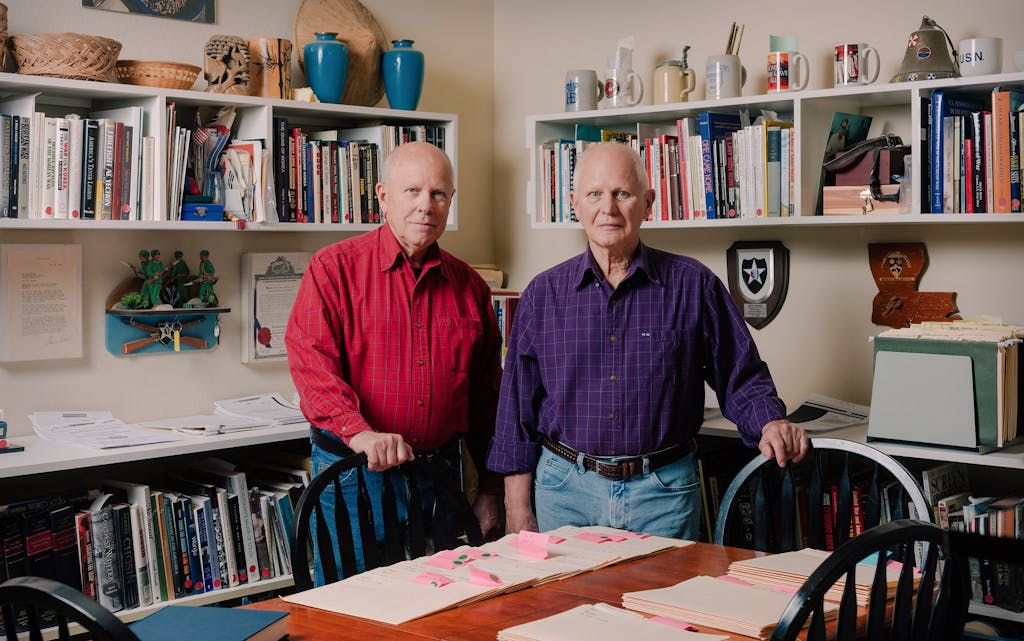

Hal was sitting in his small bedroom office, within the clean, orderly apartment he has shared with his brother for twenty years. He is about five foot six, with a ring of white hair around his head. Ted looks very much the same. Indeed, they appear to be twins, though Ted, 77, is two and a half years older. They dress alike too, in the summer wearing khaki shorts, tucked-in black shirts, and running shoes. But Ted is pushy and loud, a fast-talker, while Hal is shy and introspective, a historian. Each has been married and divorced, and Ted has a grown son. Every morning they wake up at 5:30, walk their two dogs, and sit down to work, collecting the names and stories of the dead.

Although the dining room is crowded with hundreds of books and pamphlets on the war, they spend most of their time at computers in their bedrooms. Ted handles internet security, bookkeeping, and letters and phone calls; he has a bigger bed and a smaller desk. Hal, who does programming and writes all the text, has a cot and a bigger desk. On the office walls are bulletin boards, a large map of Korea, and shelves full of binders labeled with titles like “Air Incidents: B-29,” “Bomb Squadrons,” and “Frozen Chosin.”

Hal sits in front of six monitors, where he can readily pull up official battle reports or interactive maps of Korea. “If someone says, ‘I was in Company G at Chipyong-ni,’ I can say, ‘Okay, you were right here.’ ” Another screen showed the IP addresses of all the computers that were using the site; some, he said, were contractors working for the DOD. They came all the time, he said, to use the project’s maps and mine the database to make corrections to their own flawed lists.

The Barkers do all of their work under the unforgiving eye of their father, whose medals and photos decorate a wall of the apartment. While there are numerous black-and-white group shots of him as a young Marine, it’s two color portraits that drew my attention. In the first, taken in 1942, when he was 22, Barker wears a white dress uniform and smiles confidently into the camera, as dashing as a young man can be. In the other, taken in 1957, four years after the Korean War ended, he has on a dark blue uniform, his chest covered with medals, a sword in his left hand. There’s no joy in his smile or in his eyes, which peer into the distance, as if he can’t wait for the photo session to be over.

Lieutenant Colonel Barker survived the war, but he didn’t escape unscathed. “He was really angry,” said Hal. “He was a very strange guy. He was a great war hero and a great Marine. But as a person, there wasn’t anything there. He had no sense of humor and was completely self-absorbed.” Both brothers said they can’t recall him laughing or even smiling after the war. Hal never told him about going to that 1982 reunion. In fact, five years later, the two stopped speaking altogether.

My dad, Army Colonel Robert M. Hall, didn’t talk much about the war either. He was a veteran of World War II and Vietnam, but the war that touched him the most was Korea. He had gone there at age 33, as a surgeon, wound up at a regimental collecting station (where the wounded were treated before being sent to MASH units), and was soon promoted to chief medical officer of his regiment. But he never mentioned this when I was growing up, and he sure wouldn’t watch M*A*S*H, the movie or TV show. “His hair is too long,” he’d say, pointing at Alan Alda, who played the surgeon Hawkeye Pierce, and then walk out of the room. He was difficult to connect with, and the only time he would reminisce about the war was when he was around old Army buddies. He thought we wouldn’t understand—or that we were just humoring him.

Dad was a tall, reserved man who prided himself on playing by the rules. He grew up in Raleigh, blowing the clarinet, idolizing Artie Shaw, and wanting to be an orchestra conductor, but he went to Harvard Medical School and joined the Army in 1944, as a medic, to fight the Nazis. When the Korean War started, the Army put out a desperate call for medical personnel, and Dad, then a doctor with the American Medical Association, signed up, joining the Second Infantry Division. By the time he came home, he’d decided to make the Army his career. But he was never gung ho about it. In fact, Dad was a flaming liberal, and he always encouraged his kids to fight for the little guy.

One military battle I did know about took place in February 1951. For much of the previous six months, Chinese and North Korean troops—a force of 135,000—had been kicking the UN forces’ butts. At Chipyong-ni, a mountain village, a group of about 5,000 American and French soldiers were surrounded by three Chinese divisions. As the regimental surgeon, Dad worked with seven other American and French doctors, as well as more than 150 nurses and aidmen, around the clock for three days straight, operating in freezing temperatures as they were bombarded by constant mortar and rifle fire. It was like an episode of M*A*S*H set in hell. They lost only two men, in part because they gave whole blood transfusions instead of plasma, something that had rarely been done by U.S. doctors at the front. On the third day, reinforcements arrived, pushing back the Chinese. Chipyong-ni was one of the UN forces’ first victories and would prove to be a turning point in the war.

We had a framed print of a painting of that rescue scene when I was growing up with my four siblings. Every time we moved—and we moved a lot—that painting would get a prominent place in our new house. I remember studying the looks on the soldiers’ faces as they rushed forward into battle; one in particular looked terrified and resolute at the same time.

In 1987 a sergeant who’d served with my dad at Chipyong-ni wrote him and enclosed a copy of a couple of pages from The Medics’ War, a book published by the U.S. Army Center of Military History. At Chipyong-ni, the author asserted, because of a “deficiency in the number of doctors and in the quality of their training,” an untrained sergeant had heroically taken care of the casualties. Dad, retired and living with my mom in Raleigh, couldn’t believe it. He and seven other doctors had spent 72 hours operating nonstop in mud and blood, and their efforts had saved hundreds of lives. And now the Army had written them out of history.

I remember thinking, Dad, relax, it’s only an Army book—no one’s going to read it anyway. I really didn’t understand what he had been through—and so I didn’t comprehend the magnitude of this insult. He was seventy and at loose ends, sitting around the house. But now he grew determined to make the Army admit its mistake and print the truth. Like a lot of career soldiers, he was bitter about the way he had been treated. He’d given his life to the service: World War II, Korea, Vietnam, and then running the post hospital at Fort Sam Houston, in San Antonio. At one point he was promised he’d be made a general, but that never happened. He wasn’t going to let the Army screw him again.

He started poring over old photos and maps. He got in touch with former comrades, some of whom he hadn’t spoken with in 35 years. He traveled the country, talking to veterans’ groups. He and my mom twice went to France, where he met with other surgeons who’d been at Chipyong-ni. They traveled to Korea and went to the battlefield. Finally, he sat at his cluttered desk—my mom had one next to his, where she, a quilter and author, worked on her own projects—and began typing. After years of frustration, he had found purpose and meaning, and he sat there for hours every day, for weeks and months on end, writing about what happened, with footnotes. Then he put it together into a booklet and made twenty copies, each with a color photo of that battle-scene painting that he hand-pasted onto the cover. I still have my copy of “A Review With the Identification and Documentation of Errors and Untrue Statements in the Medics’ War.”

Dad probably knew on some level that this was a lost cause, that he’d never get justice, but that didn’t stop him. He mailed the booklet to the Center for Military History, the head of the Second Infantry, and some of the men he had spoken to. The Army’s chief historian wrote him and acknowledged the mistake but said all he could do was fix the error when the book was reprinted. That wasn’t good enough, and Dad kept talking to people, tracking down more medics who’d served at Chipyong-ni. They were upset too and thankful he was fighting to tell the truth, which fueled him further. He would add to his manuscript, come up with a new version, print twenty more copies, and he and Mom would send them out again, to more and more bigwigs: senators and representatives, the surgeon general, the chief of staff of the Army. While some were sympathetic—my mom remembers that North Carolina senator Jesse Helms expressed interest in helping—there wasn’t much they could do. Dad sent out a dozen revisions through the nineties and into the aughts. By that point, the Army was ignoring him. Finally, around 2007, he began to lose steam. He was ninety and felt he’d done the best he could.

Like my Dad, Hal Barker became obsessed with uncovering the truth about the war. He interviewed his father’s combat buddies and wrote hundreds of letters and made hundreds of phone calls. He also visited the National Archives, where he copied thousands of battle records. In 1982, when the Vietnam memorial in Washington, D.C., was dedicated, some of the vets he’d befriended started calling to ask why they didn’t have something similar. There was a national group petitioning for a memorial, but it soon fell apart. In 1984 Hal donated $10 to the American Battle Monuments Commission, a federal agency, to kick off a Korean War memorial trust fund. The endowment grew, and Hal and a veteran named Bill Temple traveled to Washington to lobby Congress.

Two years later, Ronald Reagan signed a bill establishing a Korean War memorial, to be funded mostly by private donations, all of which were sent to the trust fund Hal had started, administered by an advisory board. Hal was gratified to see his efforts pay off, but his marriage hadn’t survived his obsession. Recently divorced, he moved to Dallas, where his father and brother lived.

By then, even if he’d wanted to walk away from the work, he couldn’t have. Increasingly well-known for his research, Hal continued to receive letters from families of missing troops seeking information. In 1993 he bought an IBM tape data cartridge from the National Archives containing the names of thousands of war dead, information that had been first typed up by a squad member, then transferred to a death or burial record, then put on punch cards with a limit of 25 characters, then typed again into early digital files—which were finally transferred to official databases. That process introduced many spelling and formatting errors, as Hal and Ted (now in the banking business but also helping his brother) would discover. For instance, the names of Puerto Rican soldiers who’d used the surnames of both parents had been truncated on the punch cards.

At the same time, Hal—a loner who preferred to work by himself—felt increasingly alienated from the board in charge of the Korean War memorial, and in 1995, when the memorial was completed, wasn’t invited to the dedication ceremony, he said. Hal was hurt, and when he learned that a kiosk, supposed to house a list of names of the dead, hadn’t been built, he wrote a letter of formal complaint to the House Committee on Veterans’ Affairs. The wounded feelings rankled for years.

Meanwhile, the growth of the internet allowed Hal and Ted to take the project to the next level. They were both computer nerds, and on February 15, 1995, they built a website, among the first personal ones in Texas. Within a few years, the site was interactive, allowing readers to write in their memories and look up old buddies. Now the Barker brothers were getting more emails and calls than ever, from researchers as well as family members of vets pointing out errors. A Puerto Rican documentary filmmaker, Noemí Figueroa Soulet, originally emailed Hal for help confirming basic information about veterans (like dates of birth and death), and she in turn helped him sort out some of the truncated Puerto Rican names. The Barker brothers didn’t know it, but they were crowdsourcing the history of the Korean War.

Ted handled the phone calls. He would be on the phone for hours at a time and sometimes connected people who hadn’t seen one another in 45 years. Once, Hal was on the phone with Temple, the friend who’d gone to lobby Congress with him, when Ted got an email from a woman trying to find out how her father had died. It turned out he’d been in the Thirty-eighth Infantry, as had Temple. Ted interrupted Hal’s call to ask whether Temple remembered the man. “Oh my God,” Temple replied. “I saw him get killed.” Fifteen minutes later Temple and the woman were on the phone with each other.

With the passing of the fiftieth anniversary of the war, the Barkers’ project (Ted had come on full-time) was featured on CNN. Fellow researchers sent valuable information. A retired vet and author in Maine who’d studied the official data shared with the Barkers a list of 2,452 non-battle deaths. A retired cartographer and history buff in St. Louis went to the huge Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery and photographed the headstone of every Korean War casualty—there were more than a hundred—and sent them to Hal, who put them on the individual pages. Hal learned of young men so eager to enlist that they had pushed their birth date back a year or taken the name of someone else from their town, and he made corrections.

Nearly every year, Hal would go to the Twenty-third Infantry’s reunion and talk to former soldiers and family members about what he’d learned. The wives, Ted said, “would be sitting there with their mouths open. They’d say, ‘My husband never told us any of this.’ ” Hal would always bring along maps and command reports, because he knew he would encounter veterans who’d say they were young and heedless back in 1951 and now had no idea where they had been. Hal would show them exactly where they had slept, marched, and fought.

But their dad never went with them. “He disowned us,” said Ted. “My old man hated the fact that Hal spent his time looking into his career as a military man.”

Hal said he didn’t talk to his father for the final twenty years of his life. “When I started,” Hal said, “I was trying to find out why he was the way he was. I looked at it like a lot of kids do: ‘Was it my fault? Did I do something wrong?’ I realized, No, I didn’t do anything wrong. What I discovered was that thousands of other families had the exact same experience.”

I certainly never wanted to join the Army. Spared the galvanizing events that had shaped my dad—the Nazis, a communist invasion—I was a slacker, living the life of freedom that his sacrifices had provided. I played in bands, as he might have done had he been born four decades later, and dropped out of law school, trying different professions before becoming a journalist. When I was hired at this magazine, I found myself working on long, complex stories and becoming obsessed with them, researching, interviewing, traveling, taking months to finish. Many of these were articles about men and women trapped in the prison system, denied justice. I did so many of these that my editor wrote a column calling me the magazine’s “patron saint of lost causes.” My dad got a kick out of that. He knew where that came from.

His health started to decline when he hit ninety. He had scoliosis and terrible arthritis and moved slowly through the house with a walker. Over the previous couple of years he’d mellowed considerably, losing much of his bitterness, partly from the passage of time, partly because he was often surrounded by the buzzing chaos of a large and adoring family. I remember him sitting in the living room, a glass of wine in his hand and a half dozen toddlers running around. “Ah, me,” he’d say, a beatific smile on his face.

In 2010 I heard from my sister Sue, a graphic designer who also lived in Raleigh, that Dad had been talking about publishing on a blog an account of what happened at Chipyong-ni. Dad was pretty conversant with the internet, and he loved the idea that the truth could potentially be seen by thousands of people. Sue encouraged him, and he pulled out his old files. Once again he had purpose. Sue designed the site, and I worked with him on the words, trying to massage his Army diction for a general audience. Dad’s back hurt so bad that he would lie on the bed, pillows all around him, and write on my mom’s laptop. In the versions he emailed me, he kept referring to himself as “the regimental surgeon.”

“Dad, it’s okay to use the word ‘I.’ In fact, the more personal your blog, the better,” I said. But he was old-school, and mortified. You just didn’t write about yourself.

Sue and I told him he couldn’t simply throw the blog onto the web; he had to alert people who might be interested. He’d referred me to the Korean War Project, which he contacted during his battle over the book. I emailed Hal, who remembered my dad and his struggle with the Army. Hal had even been to the battle site, and he asked me to see if Dad remembered the small building near the schoolyard that had served as an aid station. (He did.) Hal said he would do whatever he could to help and promoted the blog on his site.

“This blog was started,” Dad began his account, which he published on Blogger in August 2010, “to present the true story of how the wounded were treated at Chipyong-ni.” Encouraged by the responses he received, he added more posts—one about meeting up with some African American soldiers in World War II and another describing a photo of him that accompanied a 1951 story on Chipyong-ni in the Saturday Evening Post. My mom remembered him sitting on the bed and reading the comments with pride. “Thank you, Dr. Hall, for sharing your stories,” one said. That meant the world to him. “I can’t believe I’m reaching all these people,” he’d say, like a teenager on social media.

But his health took a bad turn, and he died five months later. We buried him at Arlington National Cemetery, and when the honor guard fired a three-volley salute, I cried like a baby.

It’s hard to get the names of the dead right. In the early eighties, Robert Doubek, the executive director of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, proofread an official DOD list of 58,000 names eight times, over the course of ten months, for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. In the end, the wall had about a hundred spelling errors. The Korean War presents a greater challenge because so many mistakes were introduced in the repeated transcribing of the casualty lists. And unlike in Vietnam, there was no official definition of the combat zone, so each service branch decided for itself what the boundaries were and which of the dead should be included.

Over the years, as Hal and Ted gathered information, they told DOD webmasters and public affairs officers about errors: names that were incorrect or missing, omissions they felt should be included. They were told it wasn’t so simple for the department’s analysts to make changes. They needed proof, and most of the changes had to come from a family member. There was a chain of command.

In 2011 the National Archives put the official casualty list on its website, and it became clear that of the thousands of corrections the Barkers had sent to the DOD, the list reflected only about five hundred. Many names were still wrong, including those of Puerto Rican, Hawaiian, and Native American troops. And the list didn’t include the hundreds who had died in plane crashes in Japan and in the waters around Korea.

It’s hard to get the names of the dead right, but it was infuriating to see mistakes like these, ones that easily could have been prevented.

Hal would not be discouraged, and he continued to gather stories and make corrections. But the very quality that made him so good at what he did—his solitary doggedness—sometimes hurt him. He didn’t always work well with others, especially those in bureaucracies. His biggest fight would pit him against the Korean War Veterans Memorial Foundation, the successor to the advisory board that built the original monument. For years it was led by Colonel William E. Weber, a Korean War hero who in 2014 began to talk with Hal about using the project’s database for a planned wall of names to be added to the existing memorial. Hal initially resisted the idea. He was still miffed over how the advisory panel had treated him. But Weber persevered, emailing Hal that his list was “far more accurate” than any other. Hal reconsidered and spoke with a lawyer, who recommended asking for a contract and some compensation.

All goodwill vanished when the two got on the phone. Hal said Weber offered him a mere $20 to cover the cost of FedExing a CD-ROM copy of the database. Hal was baffled. He hadn’t expected to turn a profit, but he and his brother had spent decades on the list, and they weren’t just going to give it up. He said no, and Weber upped the offer to $200. Again, Hal said no, but this time he broached an idea—he would give the foundation the list if members would put it into a book and print a thousand copies. Weber said that was too expensive.

Retired lieutenant colonel James Fisher, the executive director of the foundation, said he heard a different story. “I’m going to tell you what Weber told our board. I don’t know if it’s true or not. He said, ‘The Barker brothers want about $200,000 for the use of their names.’ ” Hal laughed when I relayed Fisher’s story. “He’s a lying motherf—er. You can print that.” (Weber agreed to an interview in September 2021 but never responded to subsequent phone calls or emails. He died on April 9, at age 97.)

After that exchange, Hal and Weber had no further contact, and in 2016, when Congress approved the wall, it mandated that the list of names come from the DOD. The Barkers, in other words, were officially out of the picture. But in 2019 Hal, having learned that the plan was to put the 36,634 names from the National Archives on the wall, wrote to legislators and other officials, calling the figure “inaccurate” and claiming there were more than a thousand misspellings. At a subsequent meeting of the National Capital Planning Commission, one of the commissioners, Mina Wright, asked Colonel Richard Dean of the foundation about these claims, and he responded that the Barkers “want to be paid for that data.” Wright asked, “This is a shakedown?” to which Dean said, “Could be.” After all the work they’d done, the Barkers, and Hal in particular, were furious. “He’s been tortured by their allegations of us being con men,” Ted told me. (Almost two years later, the NCPC formally apologized to the Barkers.)

Hal said the wall is missing the names of 595 service members, most of whom died in wartime plane crashes in Japan, Okinawa, and China, as well as the surrounding waters. For instance, in June 1953, at Tokyo’s Tachikawa Air Base, a plane that was supposed to take airmen back to duty in Korea after R&R crashed after takeoff, killing all 129 on board. It was, at the time, the deadliest disaster in aviation history. Because the flight hadn’t been a combat mission, the Air Force did not put the men on its official casualty list. But, said Hal, another 237 who also died in plane crashes in the seas are on the list. There’s no apparent rationale behind who made the list and who didn’t. A dot on one of his maps signifies a crash in the Philippines that killed 13; for some reason, one of the dead made the list, the other 12 didn’t.

The bigger problem is the number of misspellings and other errors, which the Barkers see as an egregious show of disrespect to the fallen. In March and April, Hal and Ted scrutinized the finalized list of names, comparing it with their list. The brothers said they found an alarming 868 misspelling and formatting errors—eight times the number of mistakes on the Vietnam wall, in a war with almost 22,000 fewer deaths. Among the errors were the inaccurate names of four Medal of Honor recipients, including Mitchell Red Cloud Jr., who later became the namesake of the Navy cargo ship U.S.N.S. Red Cloud; on the official list his last name was rendered as “Redcloud.”

Fisher said the foundation knew the DOD list was flawed, so back in 2019 it began comparing the names with those on the Barkers’ website and other online databases. The foundation also had its staff and interns go to websites such as Find a Grave to check headstones. The group sent a revised list to the DOD, which agreed to take the changes into account as it did one last vetting before releasing a final version. Fisher told me then that he thought they had taken care of most of the errors. “I think it will be a beautiful memorial. This wall is going to touch the heart.”

As for the missing names, Fisher said, there are limits to how far the bureaucracy can bend. “What the Barker brothers are doing is admirable,” he told me in 2021. “But we have to follow the law”—which means following the official DOD list. “They’re going to have to prove their case. ‘This guy should be on the wall.’ Okay, where’s your proof? If you have someone shot down in the sea, a family member has to petition it, not the Barker brothers.” Fisher said the foundation has left room at the bottoms of the panels for another six hundred names to be added later, and if that’s not enough, they’ll find other ways to honor anyone who was left off.

Hal said no amount of extra space will redeem the project. “This wall is going to be a colossal embarrassment.”

A month before the wall was set to be unveiled, I decided to check it out, accompanied by the foundation’s Colonel Dean. I’d visited the original memorial several times over the years, and I’d always found it moving: nineteen 7-foot-tall statues of men on patrol, wearing ponchos over their rifles, trudging through foreign terrain. They don’t look heroic—they look like sleepless, dirty, dogface grunts who are far from home. As a civilian, I imagine this is what war is like.

The new wall, a large semicircle of gray granite, is set a little ways beyond the statues. Dean walked me around it, pausing halfway through to show how, because of the structure’s design and position, the nineteen men are now heading toward the names of the dead. The effect is breathtaking, as though the men of a lost patrol are on the verge of reuniting with their long-forgotten brothers.

But then there are the names. As we walked along the wall, I found the names of the Medal of Honor winners the Barkers had said were misspelled. “John K Koelsh”—a helicopter pilot who was captured after attempting to rescue a downed comrade and who later died as a POW—is on the wall, but as I knew from seeing a picture of his tombstone on the Barker brothers’ website, his name was actually “Koelsch.” In the years after the war, his name also adorned the U.S.S. Koelsch, a Navy frigate. Ambrosio Guillen was a young man from El Paso who, though critically wounded in battle, led his men in hand-to-hand combat to beat back the enemy. His tombstone, with the correct spelling, is on the website—just as Guillen’s name appears on the front of Guillen Middle School, in El Paso—but here at the memorial, his last name reads “Guilien.” A third young man who died for his country is listed as “Fernando L Garcia,” but a memorial to him in his hometown of Utuado, Puerto Rico, pictured on the website, shows that his full name is Fernando Luis García Ledesma. He had rolled over onto a live grenade to save a buddy.

It’s hard to get the names of the dead right, but it was infuriating to see mistakes like these, ones that easily could have been prevented. These young men had died for their country six thousand miles from home. I thought about how members of their families will feel when they see their botched names carved in stone.

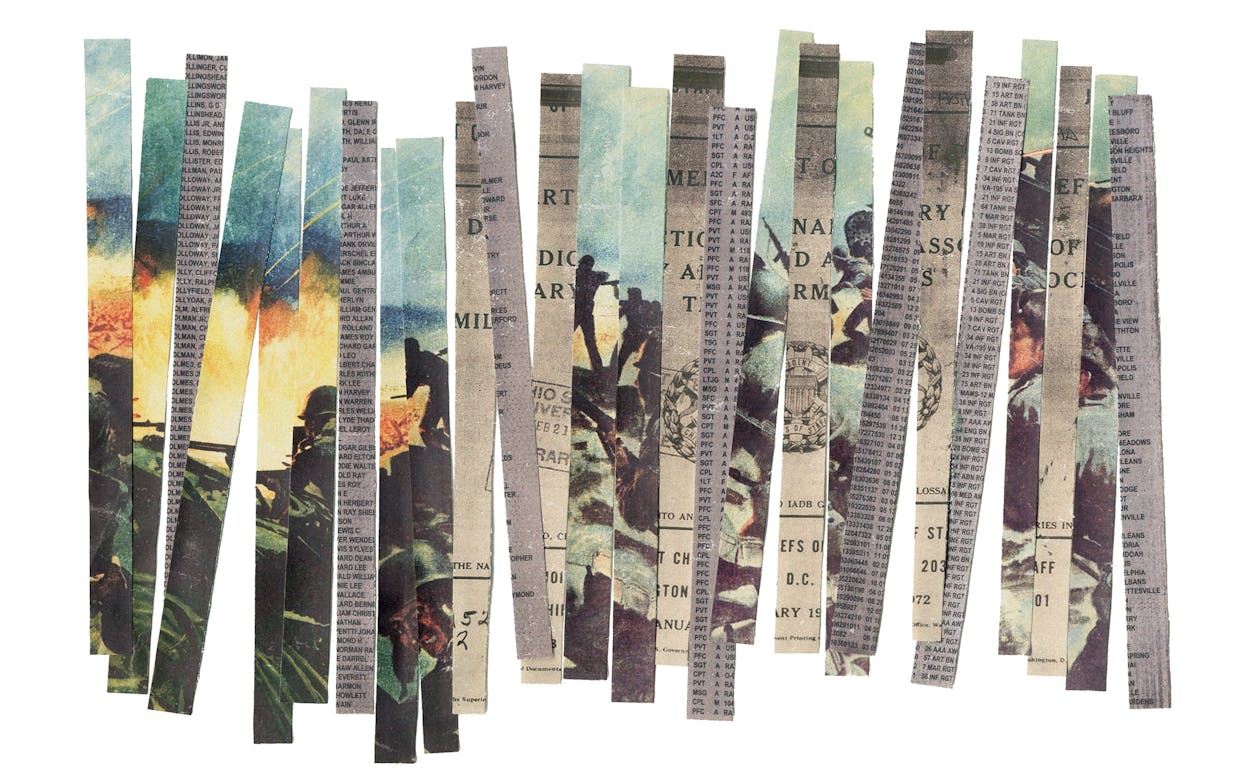

Back in January 2021, the Barkers decided to publish their own list of names. The idea was to put the painstaking work they had done over the past thirty years into a book of the Korean War dead. There wasn’t going to be anything fancy about it. No photos, no maps. Just names and essential statistics.

They found an underwriter in Mary Urquhart, a longtime Los Angeles philanthropist and former memorial wall foundation board member who had helped pass the legislation mandating the wall. She had been the foundation’s director of special events but ultimately parted ways with the organization. Urquhart has been a supporter of the Korean War Project ever since a 2017 fund-raising trip to Korea, when she learned about the Barkers. “Hal and Ted Barker have been working tirelessly on this, day in and day out, for decades, spending all their time, all their finances, in order to compile an accurate list of names,” she said. “What they have done is incredible, and they should be honored for it. Anything other than praise for their work is unacceptable. And in what universe would you not want to get the names right?”

Because so many names on the wall were incorrect, Urquhart volunteered to pay for the pressing of five hundred copies of the book, with its more accurate list. The end result is a four-pound, 525-page volume, with line after line containing the names of everyone known to have died in the war, along with birthdays, hometowns, units in which they served, places and dates of death, and official status—KIA, MIA, MIA BNR (body not recovered), PW RCV (prisoner of war, remains recovered), or PW BNR.

The copies were delivered last August, and Megan Marx received one of them. She opened to the A’s. There it was: Dwight Clark Angell, from tiny Lamar, Colorado. MIA BNR. She looked up his brothers in arms who’d died with him. As she read the names and statuses of other men and women, she was overcome with emotion.

“All these names,” she told me, “these names tell a story. This is history.”

And history is never settled. The day after Hal sent the book to the publisher, he and Ted were again at their desks answering emails and phone calls, making corrections. There’s an elegiac air to much of their labor; many of the men they’ve been talking to for thirty years are in their nineties and dying.

Watching the Barkers work, I thought of my dad sitting at his computer, obsessively writing, revising, reprinting, remailing—trying to tell the truth about what happened over three days and two nights in a small Korean mountain town decades ago. He never wanted a medal for Chipyong-ni. Like most soldiers, he just didn’t want to be forgotten.

This article originally appeared in the August 2022 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Forgotten No More.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Military

- Dallas