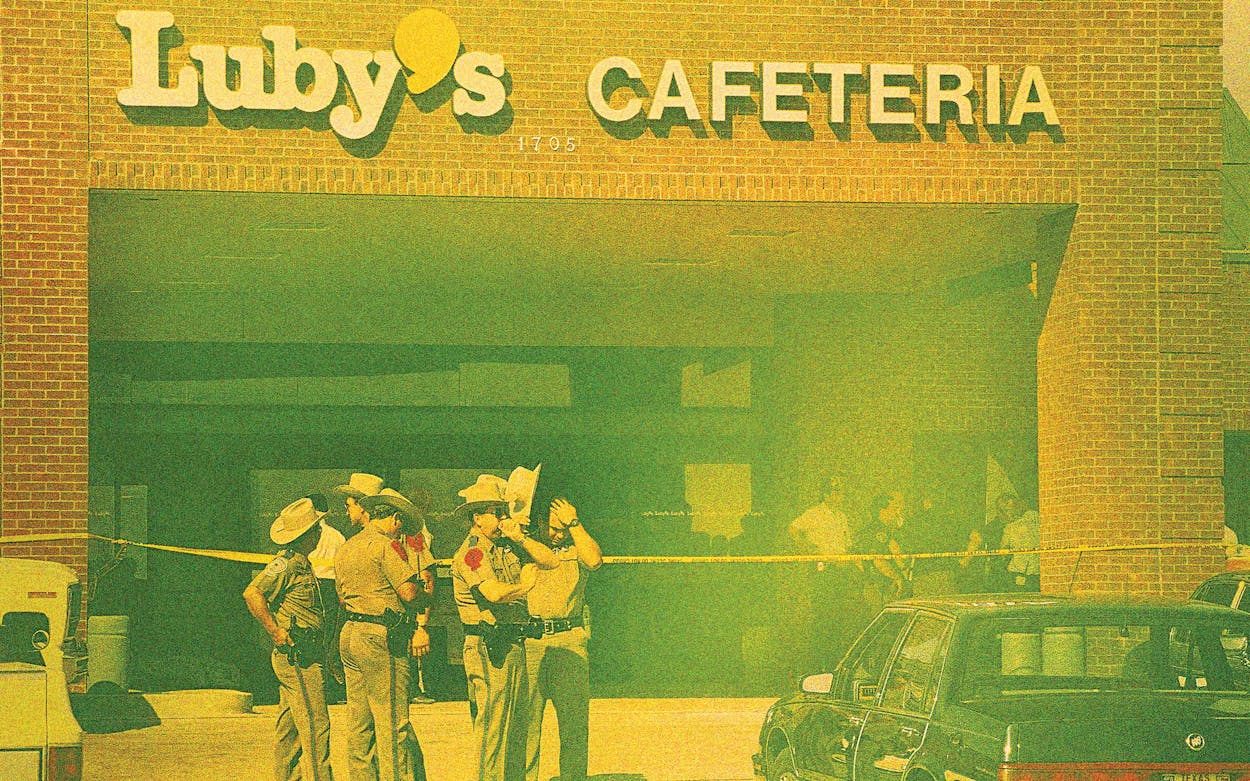

For roughly ten minutes at a Luby’s Cafeteria in Killeen, a man moved from patron to patron, shooting them at close range with a Glock 17 and a Ruger P89. As police closed in, he turned one of his guns on himself, ending what was then the deadliest mass shooting in modern U.S. history. The killer took the lives of 23 people on October 16, 1991, and wounded roughly two dozen more. Dozens of others survived without significant injury, carrying the memories with them for years afterward. But the massacre’s legacy echoes not just in the minds of those who made it out, but in the Texas penal code, where one can find a cluster of gun laws that have transformed the state.

The 24 Luby’s deaths were 6 more than were recorded 25 years earlier on the day of the University of Texas tower attack, which was the country’s deadliest shooting until a gunman murdered 21 people at a California McDonald’s in 1984. Both events shocked a nation that was unaccustomed to such slaughter. But by the time the Luby’s massacre outstripped them, a certain narrative had begun to take hold. In the 33 years from 1949 to 1981, three mass shootings of ten or more people took place in the United States. In the nine years from 1982 to 1990, six occurred. The bloodletting had become so familiar that hours after the Luby’s massacre, Peter Jennings opened his World News Tonight broadcast by saying, “It has happened again.”

Americans asked themselves difficult questions in the weeks that followed: Why did he do it? How could this happen? And, perhaps most prominently, how many lives could have been spared if someone else in the restaurant had been armed?

Suzanna Gratia Hupp had a clear answer to that last question. The 32-year-old chiropractor had been eating lunch with her parents when the gunman opened fire. “I was fully, totally prepared to blow this guy away,” Hupp would later testify before the Texas Senate. “I had good position with the table to prop my arm on, and he was standing up with his back turned three-quarters in my direction. I reached back for my purse, and that’s when I realized I’d taken the gun out and left it in the car.” Hupp didn’t have her .38 Smith & Wesson on her because in Texas it was illegal to carry a gun in public—as it had been since Reconstruction.

Reeling from the attack that left both of her parents dead, Hupp began sharing her frustration publicly. “I know some of this sounds a little funny now, but I wasn’t especially angry at the guy who did it. That’s like being mad at a rabid dog,” Hupp says today. “I was very angry at my legislators for legislating me out of the right to protect myself and my family. And I was angry at myself for having obeyed a stupid law that I think got a lot of people killed.”

The nation was already in the midst of a heated debate about such laws, as states loosened gun legislation in response to rising crime rates. A wave of concealed-carry legislation kicked off when Florida legalized the practice in 1987. Six more states followed over the next few years, and Texas almost joined them. Just five months before the Luby’s attack, the Texas Senate passed a bill legalizing concealed carry, but it stalled in the House.

Passing similar legislation was a top priority for state lawmakers in 1993, and with Hupp as a vocal supporter, they got a lot closer. A bill that would have allowed the legalization of concealed carry via referendum passed the House and the Senate, and though it was vetoed by Governor Ann Richards, it got the ball rolling. Richards lost her reelection bid the following year, and the veto was widely cited as a reason. “She’s gonna take away your gun,” George W. Bush warned voters during the fight for the governorship.

“In ’95, Bush became governor, and he promised, ‘If it passes, I will sign it,’ ” recalls Jerry Patterson, a legislator who authored Senate Bill 60, which legalized concealed carry. During a Senate hearing on the bill, Hupp provided vivid, even theatrical testimony; at one point she stood up and pointed her finger, like a pistol, at lawmakers to demonstrate what it feels like to face a shooter. By the following year, anyone 21 and older who could pass a background check, take a gun-safety course, and pay a $140 licensing fee could carry a concealed weapon in Texas.

Texas right-to-carry laws expanded radically in subsequent decades, making it the most gun-friendly state in the union. “I passed that bill. It gave me a tremendous amount of notoriety or fame, depending on how you view it,” Patterson says. “So every legislative session after that, everyone’s asking, ‘What can I do that’s gun friendly?’ It just became more and more and more, and the stupid thing is we got people carrying guns that don’t know when they can use them and be compliant with the law. And that’s not good.”

As it turns out, legislators could do plenty of things that were gun friendly. Until 2016 open carry was illegal in Texas; today you can saunter down Main Street with a semiautomatic rifle hanging jauntily from your shoulder strap. On August 1, 2016, the fiftieth anniversary of the UT tower shooting, concealed carry became legal on public university campuses. And as of 2021 Texans no longer need a permit or training to carry a firearm.

The Luby’s massacre, by the way, is now merely the country’s sixth-deadliest mass killing, tied with the attack on an El Paso Walmart in 2019 and just one spot behind the 2017 attack in Sutherland Springs, which was cut short by an armed resident after a shooter killed 26 churchgoers. The 2022 assault on Uvalde’s Robb Elementary School is the nation’s ninth-deadliest shooting, the UT shooting is eleventh, the Fort Hood shooting of 2009—Killeen’s second entry in this grim sweepstakes—is thirteenth, and the 2018 killing of ten at Santa Fe High School is twenty-ninth.

Sutherland Springs. Killeen. El Paso. Uvalde. Killeen again. Santa Fe. Since 1991 there have been 24 mass shootings in the country in which ten or more people were killed; six of them have occurred in Texas, a state awash in guns that, somehow, don’t make many people feel much safer.

Even Hupp foresees a seemingly endless arms race on the horizon. She served in the Texas Legislature from 1997 to 2007 and now works as the director of government relations for Attorney General Ken Paxton. Explaining why she fought to have campus carry legalized in Texas, she raised the specter of still more-formidable adversaries in our future. “There’s somebody out there, right now, thinking, ‘I could get a bigger body-bag count,’” she warned.

This article originally appeared in the December 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “A Massacre’s Echoes, Decades Later.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Killeen