A few months ago, Susanne, a 58-year-old German expatriate living in Houston, entered local gun store Collectors Firearms with her husband on the hunt for a charming antique. She perused the converted Barnes & Noble, whose massive inventory of weapons and military regalia—including Nazi artifacts—resembled a private museum more than a mom-and-pop shop. Above rows of cases with neatly displayed collectible pistols, swords, and daggers, Susanne spotted over a dozen finely stitched, handmade flags from Germany hanging from the ceiling. She recognized them as club flags, which are distinctive emblems that typically represent civic organizations or hobbyist groups.

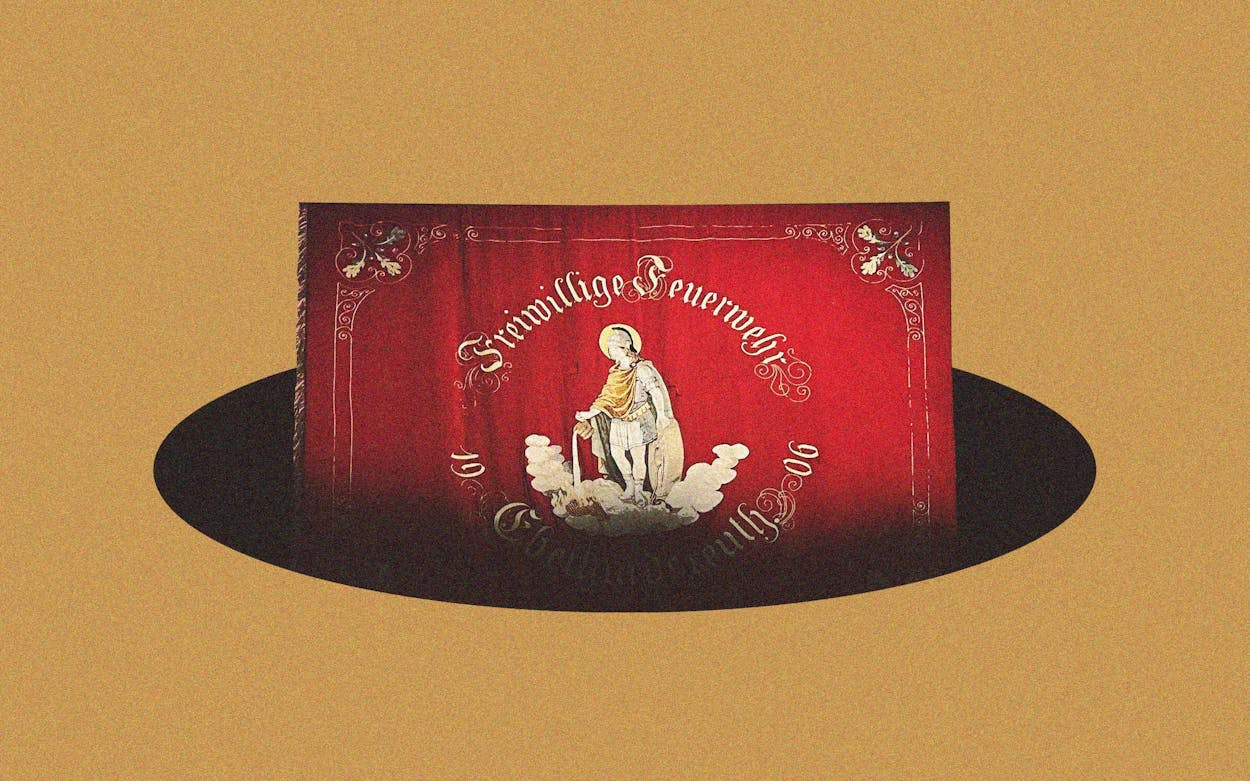

One flag in particular stood out to her: a bright red banner embroidered with the image of Saint Florian, the patron saint of firemen, along with German text that translates to “Eberhardsreuth Volunteer Fighters 1906.” On the other side, the coat of arms of Bavaria was stitched against a white backdrop underneath a German firefighter motto, “God to honor, neighbor to defend!” Susanne, who asked to remain anonymous to protect her privacy, snapped photos of the flag and, later that evening, sent them to the Eberhardsreuth volunteer fire brigade in a private Facebook message. She didn’t realize that in doing so, she was solving an eighty-year-old mystery and triggering a complex debate about the restitution of cultural property taken from Europe during World War II.

Located in the state of Bavaria, Eberhardsreuth is a small village in southeast Germany with a population of around six hundred. When Susanne first shared the photos, Dennis Marxt, commander of the Eberhardsreuth volunteer fire brigade, was unsure if it was even the group’s flag. He eagerly shared the photos at the fire brigade’s annual department meeting, which included active and nonactive members. The oldest member of the group was born in 1936; he told Marxt he remembered seeing the flag as a boy and knew its history.

In 1906, after nuns embroidered it in a monastery in the nearby town of Thyrnau, the fire brigade threw a small festival at which the local priest blessed the new banner, Marxt said. As the fire brigade club flag, it was displayed or carried during parades and religious ceremonies, such as Easter and Saint Florian’s feast day, as well as wedding and funeral processions. Then it went missing in 1945. Most of the elder members of the brigade believed the flag had been destroyed in battle, when General George S. Patton’s Third Army liberated the town from the Nazis. Now that they knew the flag that would have been used in their grandfathers’ funeral ceremonies had not been destroyed, Marxt and his fellow volunteer firefighters wanted it back.

Marxt first tried to appeal directly to Collectors Firearms. He sent a short message over Facebook that went unanswered. After a week, he followed up again and received a response: “The owner has a lot of work to do and isn’t easy to reach.” Undeterred, Marxt then solicited the help of his mayor, whose messages also went unanswered. Thinking there was a language barrier preventing a dialogue, the mayor then contacted Markus Hatzelmann, the German deputy consul general in Houston, to help facilitate a conversation with Danny Clark, the owner of Collectors Firearms. Hatzelmann’s efforts were futile. Clark told him he had no interest in returning the flag.

Meanwhile, unbeknownst to Marxt, Susanne returned to the store a couple weeks after her first visit. She intended to purchase the flag so she could donate it to the fire brigade. But an employee at the store told her the flag was for decorative purposes only, and it wasn’t for sale.

Clark told Texas Monthly the flags have been hanging in his shop for years—though he said he doesn’t have any documentation for the chain of title or recall where he purchased them—and said the banners add to the store’s character. “It would be a pain in the ass to get the thing down,” Clark explained of the flag in question. He said the German fire brigade offered to fly him to Eberhardsreuth and give him a hero’s welcome in exchange for donating the banner, which he paid approximately $2,500 to $3,000 for. “I don’t give a s— about any of that,” Clark said.

After he refused the offer, Clark says he began receiving harassing emails and phone calls. He says some Germans left disparaging reviews on Yelp and Google Reviews, subsequently deleted, that called him a crook and demanded he return the flag, so he dug his heels in more. “I’m not selling the flag now. And especially I’m not selling the flag once you started threatening me and trying to ruin my reputation,” said Clark.

Experts in art restitution argue that returning displaced cultural artifacts builds international goodwill and helps establish stronger relationships with our allies. “Do we want to be the ugly American and always deal with things from a monetary standpoint?” said Robert Edsel, founder and chairman of the Monuments Men and Women Foundation, a Dallas-based nonprofit that helps recover artworks and other cultural objects that went missing during World War II and return them to their original owners.

But in early May, the decision of whether to keep the flag was made for Clark. One Saturday morning, when the Collectors Firearms owner was not working at the store, he says a man with a German accent came in with a printout of an email exchange appearing to show Clark agreeing to donate the flag (Clark says the printout was a fake). After unsuccessfully trying to reach Clark on his cellphone to confirm, the employee unhooked the banner from the ceiling—Clark says it fell down and injured the employee in the process—and gave the flag away.

Clark says he did not contact the police about the stolen flag, and he would not reveal the name of the employee whose head he said was split open giving it away. He also balked when asked if he would provide the security footage of the unknown person who took the flag, which he said he possessed. “It’s not going to make me money, and it’s not going to get my flag back,” Clark said repeatedly.

Once the flag went missing from Clark’s store, he said all of the negative comments on Yelp and Google Reviews were removed. “I’m sure that flag’s back in Germany,” he declared.

It doesn’t appear to be, yet. Back in Eberhardsreuth, Marxt says he hasn’t seen the flag. “We are, of course, disappointed,” he said. “But we have a positive side to it because up to now, we didn’t even have a photo of it.”

If the flag is returned, Marxt plans to throw a celebration based on Bavarian tradition. “We will make a big procession to our little church of Holy Michael,” Marxt said. “We will donate a big candle in the church, and we will have a great beer festival with free beer for all.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Houston