A real home: that’s what Alexis Roberts wanted for her children. Her four young boys talked about it often, their hopes never dimming, even as the prospect eluded them time and again. “When we get our own place . . . ” is how their daydreams often began. A home implied all sorts of possibilities: a closet to store football gear, a spot to put up their own Christmas tree, a puppy.

For years Roberts and her kids cycled in and out of homelessness in Dallas. They bunked in several shelters, once hunkered down in an abandoned house, and spent a few stretches in pay-by-the-week motels. She lost count of how many social service agencies she’d visited, trying to do better for her kids. She hit bottom on the night when the five of them slept outside, in a public park with a large pond. The boys tried to make the best of it, imagining they were camping. But she didn’t sleep much. “That was my breaking point,” Roberts said.

After that she managed, with the help of pandemic stimulus checks, to buy a used Dodge SUV, which allowed her to get a better job and move from a shelter to an apartment. But the strain of those chaotic years lingered, and in spring 2021, her second oldest was struggling, flunking third grade and getting into trouble. One day, she got a call from an administrator at his elementary school who told her there was someone who might be able to help.

Not long after, Roberts pulled up to a brand-new building, the headquarters of a nonprofit called At Last, six miles south of downtown and across the street from South Oak Cliff High School. Inside she was greeted by a soft-spoken man named Randy Bowman, with deep-set eyes and a constellation of faint freckles on each cheek. Roberts didn’t know it at the time, but among the city’s business elite, Bowman had a reputation as an innovator.

As a young attorney in Dallas, he’d built an unlikely entertainment practice, shrugging off naysayers who told him it couldn’t be done outside the industry’s nerve centers in Los Angeles and New York. His first client was a young, unknown rapper named Vanilla Ice. Bowman then left his legal practice in 2001 to launch a logistics company. By the time he sold his share of the company, sixteen years later, he and his partner had been named finalists for Ernst & Young’s Entrepreneur of the Year, and their Fortune 500 customers included General Mills and Procter & Gamble.

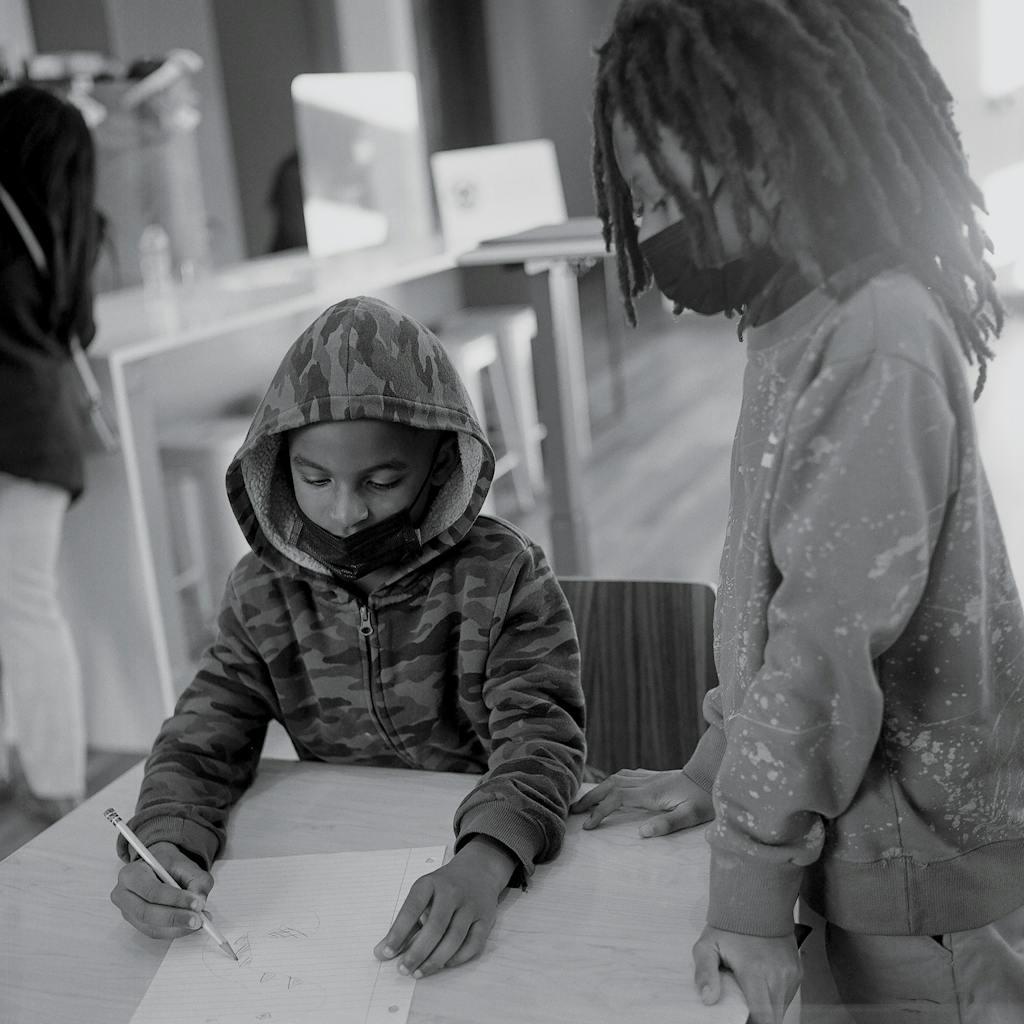

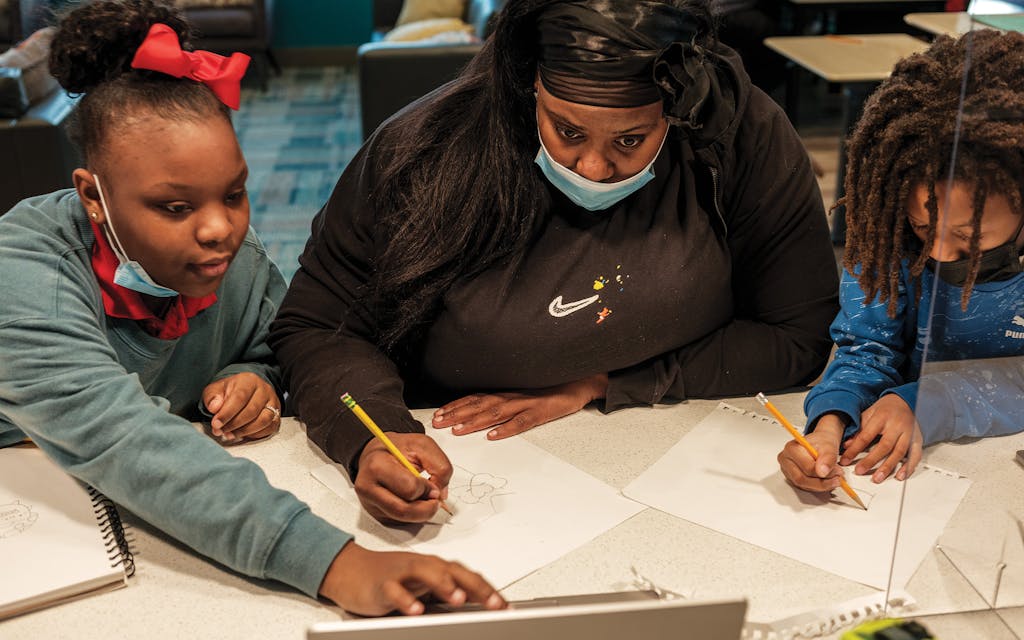

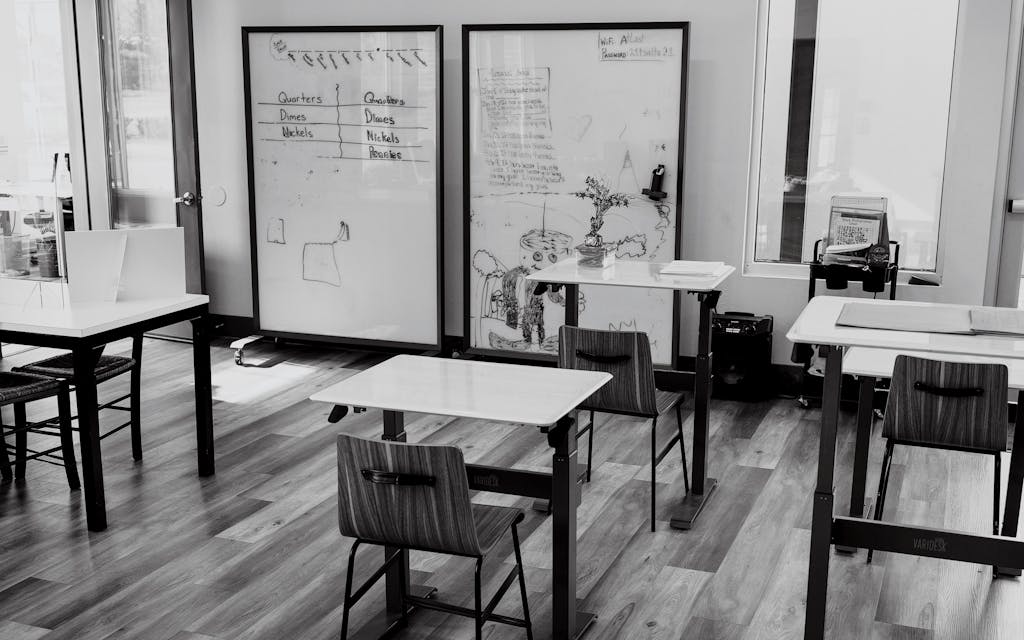

Bowman gave Roberts a tour of the building, beginning with its spacious communal area, explaining that At Last serves as a weekday home for disadvantaged kids—a “boarding experience.” She took in this central room’s soaring, sloped ceiling with a trio of skylights, its open kitchen and gray couches and scattered desks. This is where students—all of them third to sixth graders—get several hours of academic support after school before sitting down together, family style, for a meal. If needed, they also get counseling, dental care, and eye care. They still attend their neighborhood schools; the rest of the day they enjoy the kind of help and nurturing typical of a middle-class home.

The program was still in its infancy, Bowman told her, but eventually students would spend weeknights in the sixteen-bed dormitory connected to the living area. The building sits on a wooded four-acre parcel bifurcated by a creek, so the kids would have plenty of room to play, though he was also planning to have two more dorms built, each with 82 beds. This is wonderful, Roberts kept thinking, eager to enroll not just her third grader but one of his younger brothers, who would be eligible the following year.

She and Bowman then sat on a couch, and he began telling her how the program had come about. He had grown up poor in the South Dallas neighborhood of Pleasant Grove. As he later told me, he and his mom shared a coat. “And you know there’s no way to share a coat. That meant one of us went without.” His childhood was marked by episodic violence—he’d witnessed more than one murder as a kid—but that wasn’t his biggest problem. Navigating poverty was a daunting daily puzzle. There were times when he would skip school to earn a little cash, not because his mom didn’t value education but because they were desperate. “We were hungry. The lights were off. We were about to get put out. That kind of stuff.”

He’d always hated how society had viewed his mom—looking down on her because she had kids with multiple people, because she didn’t look like she had her act together. His mom, he told Roberts, was his hero. And he sees the mothers who walk through the door of At Last through the same lens.

“I see the good mother in you,” he said, “even if you aren’t able to make her evident to the rest of the world. I see her.”

I could’ve been your mom, Roberts thought, tearing up. That’s me.

As a kid, Bowman had dreamed of giving his mother the life he thought she deserved, and he’d gone on to improbable success. Now, at age 59, he’s trying to help others do the same, by attacking the problem of perennially subpar outcomes in high-poverty schools. He’s hardly the first budding philanthropist to do so, but among big money donors, he’s unusual in another sense—to Bowman, the problem isn’t abstract. He knows firsthand the challenges faced by students living in poverty. This has led him to try a radically different approach, one that considers what kids experience the rest of the day, after the last bell rings. While aiming to help kids and families, the program he created will also try to answer a provocative question: could the quality of public education in high-poverty areas be vastly improved without making a single change inside the classroom?

The epiphany struck while he was on a long bike ride, having set out from his home in the posh North Dallas neighborhood of Preston Hollow. For months he had been poring over research on what ails schools in economically distressed areas, asking himself, What’s the most intractable part of this problem, and how do I solve for that?

Though Pleasant Grove is less than a thirty-minute drive from his current home, that brief expanse seemed nearly impassable when Bowman was growing up. His mom often told him and his three siblings, “ ‘I just wish I could give you all what those rich folks across town are able to give their kids,’ ” Bowman remembers. “And I always knew exactly what she meant by that. I hadn’t seen those houses, but I had an idea—we had television.”

The city’s divisions remain stark. A recent study from UT System health researchers showed that a few miles in Dallas can mean a 23-year disparity in average life expectancy, with health outcomes strongly correlated to relative wealth.

While out riding his bike that day, Bowman queued up a podcast in which the hosts were discussing research about predictors of kids’ academic (and thus professional) success. One of the strongest, by far, is the socioeconomic status of the household from which they come. “That resonated with me in terms of my personal experience. It also resonated when I stood back and looked at it as a businessperson,” Bowman said.

Back in his home office, he did some quick math, dividing a schoolkid’s day into a simple pie chart: they’re in school 29 percent of the time and at home the other 71 percent. “It didn’t make a lot of sense to me that we’ve used the tax base to try and equalize the amount of educational resources that you receive during the twenty-nine percent of the day that you’re in school, but nothing seeks to level out the educational resources that you receive during the seventy-one percent of the day that you’re at home.”

Broken down this way, the typical approaches to education reform, almost all of them aimed at initiatives inside the school building, seemed to him profoundly shortsighted. If he’d had a unit in his logistics company that was underperforming, Bowman said, and he put all of his resources into solving 29 percent of the problem, colleagues would consider him delusional.

For decades, policy makers, researchers, and well-funded foundations across the country have targeted the considerable achievement gaps that exist along racial and economic lines. Yet students from impoverished and nonwhite families still have significantly higher dropout rates, score lower on standardized tests, and are far less likely to enroll in college than well-off white kids. Bowman had a hunch that traditional reform efforts weren’t making enough headway because they were incomplete.

So what would it look like to target the rest of the problem? Bowman’s big bet, on which he’s staked a portion of his personal fortune, is that by offering elementary school students from low-income households the kind of stability, academic enrichment, mentoring, and health care that their wealthier peers take for granted, the At Last program will lay a foundation for success.

In spring 2021, At Last welcomed its inaugural crop of students. The program is still small, with capacity for just sixteen kids, who’ll start spending nights there in May. But the preliminary data are striking. Almost every student has shown steady academic growth since enrolling, and some have seen dramatic upticks in grades—from failing all the core subjects to making the honor roll. Bowman knows that At Last still has to prove itself over a longer time period, but, he said, “if Dallas ISD could get these results, they’d shut down and hold a parade.”

The woes of underperforming public schools are both widely known and broadly misunderstood. Speaking on a radio show in October, Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick described big-city schools as “dropout factories.” His comments sparked a backlash, with officials from some districts defending gains they’ve achieved in recent years. Hyperbole aside, Patrick wasn’t wrong to point out that graduation rates aren’t what they should be. He singled out Dallas, which has the lowest four-year high school graduation rate of any of the state’s large urban districts, at 81 percent, roughly nine points below the state average. Just to the north, in suburban Plano ISD, the graduation rate jumps to 95 percent.

Patrick is far from the first to write off Dallas’s public schools. He had appeared on the show to stump for school vouchers, which would allow students to attend private schools using taxpayer dollars. The basic pitch is enticing, but as various trial runs across the country have demonstrated, stipends aren’t enough to cover tuition at quality private schools, which don’t have the space to accommodate an influx of students anyway. The problems with voucher proposals run deeper, though. As a policy solution, they presume that schools are to blame for relatively poor academic outcomes. Undoubtedly, some high-poverty schools suffer from mismanagement. But others do not, and they still struggle to contend with overwhelming challenges.

A proven way for schools to boost student performance is to get the most qualified teacher possible in every classroom. Beginning in 2015, Dallas ISD experimented with luring its best teachers to the lowest-performing campuses using pay incentives, which yielded double-digit improvements on standardized test scores in some of those schools. Rather than invest in teachers, though, Texas has mostly slid the other way. In 2019 the average public schoolteacher’s salary was less, adjusted for inflation, than it was nine years earlier. In the 2021–2022 school year, 12 percent of the state’s teachers left the profession—and 77 percent of surveyed teachers said they were considering it, while 72 percent of those surveyed had taken concrete steps to do so, citing low pay, low morale, and excessive workload as reasons.

“The reality is, even if we got the schools completely right, it does not resolve over a century’s worth of public policy decisions that have created barriers to economic mobility for kids.”

But as anyone who’s ever worked in the public school system knows, even the best teachers are not a cure-all. Some of those same Dallas schools that saw dramatic improvements were still considered failing by the Texas

Education Agency. In Dallas ISD, 85 percent of students are economically disadvantaged (meaning they qualify for free or reduced-price lunch), compared with 61 percent statewide. At Elisha M. Pease Elementary, the Dallas school attended by Roberts’s kids, 98 percent of students are considered disadvantaged.

In many ways, public schools have been set up to fail, yet they’re still expected to perform miracles. “Public education institutions across the United States, and certainly in Dallas, are pointed to as a panacea to intergenerational poverty,” said Miguel Solis, who helps run the Commit Partnership, a Dallas nonprofit trying to address economic inequity in the city. Solis, who taught in Dallas ISD as a fresh-faced college grad, then got elected to the district’s school board, in 2013, as a still-fresh-faced 27-year-old, served during the push to improve teacher quality. “The reality is, even if we got the schools completely right, it does not resolve over a century’s worth of public policy decisions that have created barriers to economic mobility for kids,” Solis said.

Elicha Edwards, a former family therapist who works for At Last as a “house mom,” knows all too well what those barriers look like for students in the program. Some have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder because of “the level of violence they witnessed in their community or inside their four white walls,” she says. Most live with single moms working two or three jobs but still struggling to make rent, keep the lights on, stock groceries. When margins are so tight, any small thing can metastasize into a crisis. Evictions are common, which tends to set off a calamitous chain reaction, including job loss, relocation into substandard housing, and kids’ having to change schools midyear. Multiple At Last families have spent days and sometimes weeks in shelters. Bowman’s program is an outlier in the education world precisely because it attempts to mitigate these disruptions, which are rooted in poverty itself.

While boarding schools for the American elite have been around since the mid-eighteenth century, there’s been only one other well-known attempt to bring that model to the urban poor. The SEED Foundation launched a college-preparatory boarding school in Washington, D.C., in 1998; it has since opened campuses in Baltimore, Miami, and Los Angeles. A pair of Harvard University scholars found that SEED’s effect on student achievement is significantly greater than the average charter school’s. They also noted the program’s expense: the D.C. program costs twice as much per student as public schools in the city. That’s one reason the program is difficult to replicate on a larger scale.

Bowman argues that one advantage of At Last will be cost efficiency. Because kids remain in their neighborhood schools, there’s no need to duplicate the resources already expended in the form of teachers, administrators, and facilities. According to Bowman, when the Oak Cliff site has been expanded to include two additional dorms, the projected annual cost for each student will be $7,500. (The state spends $10,300 per pupil in public schools.) Bowman also differentiates his program from those, such as SEED, that are narrowly focused on collegiate success.

The students he serves are disproportionately likely to become underemployed high school dropouts. A 2012 study estimated that the total cost to the U.S. economy of all high school and college dropouts, in lost productivity and increased reliance on social services over their lifetimes, was $4.75 trillion. Based on At Last’s projected expenses, Bowman calculates that if the program were to help just 15 percent of its students get their diplomas, it would provide a net economic benefit. “If I get the normal distribution of blue-collar and white-collar professionals out of this group, that’s a grand slam,” he says.

That Bowman was able to transcend his difficult upbringing is due, in part, to his ability to see opportunities where others saw impediments, whether that was as a poor kid hustling for food or as a businessman conjuring a new company out of the ashes of a defunct one. Peter Brodsky, who made his name as an investment wiz at the high-flying Dallas firm Hicks, Muse, Tate & Furst, told me that he’s sat in rooms full of big-shot investors and seen how when Bowman speaks up, everyone leans in to listen. “When I’ve got a problem, he is one of two or three calls that I’m going to make to get advice,” Brodsky says.

Bowman has an athlete’s rhythmic gait—he played football, baseball, and basketball in high school—and brims with a quiet confidence. One recent morning, I hopped in the passenger seat of his navy-blue Kia SUV, and he drove me around the town of Forney, thirty minutes east of Dallas, where he spent his earliest years. Forney has the kind of historic downtown that’s often described as quaint—well-kept brick storefronts and lots of murals depicting pastoral scenes. Bowman reminisced as he pointed out childhood markers: the local bank where in first grade he got Roger Staubach’s autograph; the old cotton gins that flank the railroad tracks; Little Flock Baptist Church, a modest white A-frame where he sat with his family in the pews every Sunday morning.

When Bowman’s mom, whom everyone called Ann Lois, attended Forney’s segregated Booker T. Washington High School in the early sixties, cotton fields stretched to the horizon. Her father had settled in Forney after serving in the Army during World War II; he found a job in a meatpacking plant and built the family home himself. Ann Lois had hoped to become the first in her family to get a college degree, but that plan was thwarted after she got pregnant during her junior year of high school.

Bowman was the second of her four children. The family was crammed into a 500-square-foot house—there was one bathroom and a tiny kitchen—next to the railroad tracks, while aunts and uncles and grandparents all lived close by. Bowman’s Aunt Mae and Uncle Jake worked at the post office. They were both deaf and “lived better than anyone else in my family,” he said. As a kid, he dreamed of working at the post office too.

One evening when Bowman was eight years old, his mom sent him and his sister to pick up a few groceries at the general store. While his sister shopped, Bowman stayed near the front, by the comic book rack. The white store owner was nearby, chatting with a friend.

The owner charged over, picked Bowman up, slung him over his shoulder, and started beating him. The more Bowman tried to wiggle loose, the more violent the man became.

He noticed Bowman eyeing the rack. “Hey boy, don’t touch any of those comic books,” Bowman remembers him saying.

Bowman tried to reassure him: “ ‘I’m not touching them. I’m just reading the covers.’ ”

The owner’s friend interjected: “Oh look at that. Little n—er is popping off to you.”

The owner charged over, picked Bowman up, slung him over his shoulder, and started beating him. The more Bowman tried to wiggle loose, the more violent the man became. His sister heard Bowman wailing and rushed over. She then screamed and dropped her groceries. A few items shattered. The owner turned and berated her, demanding that she pay for everything. She did. Then she and Bowman hurried home.

According to Todd Moye, a history professor at the University of North Texas who studies civil rights movements in Texas, “in the twentieth century in Texas, and especially in East Texas, those kinds of things happened more or less all the time.” Dallas County commissioner John Wiley Price, who grew up in Forney, was a sophomore in high school when Booker T. Washington High School was shuttered in 1967. Price recalled that segregation in the town was entrenched in large part because “the cotton community controlled Forney.”

The morning after the assault, Bowman was in so much pain that his mom and grandparents took him to the hospital, where surgeons removed a damaged appendix. Sitting behind the steering wheel on the day of our visit to Forney, Bowman lifted his shirt to show me a three-inch scar. “Every time I get dressed, take a shower, do anything, I still have a really good reminder right here,” he said.

In the story that was told and retold within Bowman’s family, the sheriff declined to charge the owner, who didn’t deny any of the allegations. Bowman believes the attack and its aftermath was traumatic for his mom, in part because she was unable to come to his defense. Her lack of education and inability to afford a lawyer had robbed her of the capacity to advocate for and protect her son. For Bowman, the lesson was clear: to take care of those he loved, he’d need to obtain the kind of money and status that had thus far eluded his family.

The following year, 1972, the family moved to Pleasant Grove, in southeast Dallas. On Bowman’s first day of school, he fell in with a group of kids on their way to Burleson Elementary. As they walked through a wooded area, a few of them started passing cigarettes and a joint, and Bowman realized he’d landed in a very different place.

One day this past June, Bowman showed me the weedy corner lot in Pleasant Grove where his childhood home once stood. The house burned down a dozen years ago, but Bowman recalled its contours: low-slung, with gray brick on the front and wood paneling on the sides that his stepfather inexplicably painted purple. All that remains is the concrete driveway and a tilted section of chain-link fence.

Many of his memories are grim ones. Standing at the site of his former home, Bowman motioned to just about every house on the block and recounted a tragedy that had befallen residents of each—a wife shot by her husband, a teenager stabbed at a party, a young man gunned down at a nearby motel. Bowman first witnessed a murder when he was eleven, watching from a few feet away as an older kid got shot in the chest after a senseless argument. “He dropped right there in the dirt, writhed around for a few seconds, and then bled out. Every fight could end in a funeral, is what I took from that.”

Amid the tumult, Bowman turned to his mom for inspiration. “She was always a person who poured into me the belief that I could make something work out of anything,” he said. She was employed as a checker at a grocery store, but when Bowman was in middle school, his stepdad started spending less and less time with the family. Ann Lois began drinking—her way of coping with depression, Bowman believes—and struggled to keep a full-time job. “She was doing everything she could,” he said, but her health deteriorated. Bowman took it upon himself to help out.

The summer he turned thirteen, he talked his way into a job in the cafeteria at Timberlawn, a now shuttered private psychiatric hospital, and did double shifts seven days a week. Legally, he was too young for such hours—“I must have looked all of nine,” he said—but the manager, Mr. Willis, knew he needed the money and took pity on him. “All right, so you’re sixteen?” Willis gamely prodded him when they were filling out employment paperwork.

Many days, he’d catch a predawn city bus and arrive around 6 a.m., then spend much of the next twelve hours scrubbing pots and pans. The job came with an invaluable perk: he was allowed to take dinner leftovers home to the family. “And this was good cafeteria food that they were serving to the folks who had the money to pay to be at Timberlawn,” Bowman said. “When there was chocolate sheet cake, I would dance around the kitchen and tell Mr. Willis, ‘You the man!’ ”

When school resumed, he kept the same job on weekends. During the week, he went straight from after-school sports practice to a gig at Del Taco, where he worked until close, a routine he kept throughout high school. Bowman never studied and rarely got even seven hours of sleep, but school subjects came naturally to him. He’d always wanted to attend some sort of college—he’d learned from his Aunt Mae and Uncle Jake that he needed an associate’s degree to get a good post office job. But mentored by his coaches and an influential high school English teacher named Dorothy Berry, and fueled by his desire to give his mom the life he thought she deserved, Bowman had begun to imagine a different set of possibilities. He graduated in the top 10 percent of his class, and after high school he headed south to Austin.

Bowman felt like he’d stumbled into an intellectual mecca. At the University of Texas at Austin, he found a group of like-minded friends who also came from poor, single-parent homes. Many of them he met through the newly formed Black Student Alliance—Bowman would become one of its presidents. “We were both kind of bomb-throwing student radicals together,” said his friend Eddie Reeves, now a partner at a strategic advisory firm in Austin. They got involved in the anti-apartheid movement, pressuring the university to divest from companies doing business in South Africa.

Other forms of activism earned them notoriety across campus. At the time, Reeves said, several UT-Austin sororities had opted not to register as official student groups with the university because it would have required them to sign an antidiscrimination pledge. But they were still featured prominently in the university yearbook. Bowman went to the publishers and asked them to change that. “We didn’t think it would be that controversial, but it exploded into a major controversy,” Reeves recalled.

The publishers pushed back, saying that the sororities had paid for their placements. Bowman proceeded to meet with leaders of other student groups, persuading them to boycott the yearbook if the sororities were included, a strategy that eventually won out. “The way he approached that, going out to build that coalition, was kind of a hallmark of the way Randy led and still leads today,” Reeves said.

A few years in, Bowman also organized a group to address the high attrition rates for Black students at UT-Austin, many of whom had never been taught how to write a term paper or how to properly study. The group’s initiative, which they called Operation Retain, sponsored an orientation for incoming Black students and set up a mentorship program. (An official at UT-Austin said that the program no longer exists but was successful enough that it served as a model for efforts that are ongoing today.)

Arthur Pertile, now a Houston attorney, was already in law school when he met Bowman, then a sophomore. They would often talk of career aspirations, said Pertile, who had also grown up poor. Bowman earnestly batted around ideas for how to help kids from backgrounds like theirs, already dreaming up plans for his own nonprofit. “What sets him apart is that he has a pit bull mentality,” Pertile told me. “When he sets his mind and he locks his jaws on something, he’s gonna stay with it.”

Bowman and Pertile both felt it was a miscalculation to return to their neighborhoods right away. Teaching, community organizing, social work—those were admirable vocations. But Bowman wanted to attain material wealth first and decided to become a corporate finance lawyer. He settled on Whittier College, outside Los Angeles. Its law school, which has since closed, offered a two-and-a-half-year program—a semester shorter than traditional law degrees—which meant he could graduate in time to land a job and cover his youngest brother’s college tuition. There he became the editor in chief of the Whittier Law Review.

He borrowed a cousin’s too-big suit to interview for a prestigious summer internship at Jackson Walker, one of Dallas’s largest firms, and while his fellow summer associates lived in upscale apartments near the downtown office, Bowman stayed with his mom. From the firm’s tony high-rise, he could stare out at his stratified hometown; his daily commute was a disorienting journey from indigence to affluence. When he brought his mom his first week’s check of $1,000, she started crying—in six weeks he would earn more money than she’d made in any of the last five years.

Upon graduation, in 1989, he started full-time at Jackson Walker. He made sure his mom never had to work again. “It was ridiculous, you know, relative to where we had been. I don’t think she ever imagined that much money coming into our family.”

At the firm, Bowman kept the kind of hours he’d cultivated as a teenager. He would work late, then clock out and drive to clubs where local musicians were playing. He’d always been interested in the entertainment industry, so several nights a week he’d scout for talent, which was often dismal. Even Pertile thought he was wasting time: “I’m telling him, ‘Randy, you know you can’t make money in entertainment law. And where you gonna pick up clients?’ ”

One night, Bowman was headed out the door of a hole-in-the-wall joint in East Dallas when he met Tommy Quon, a nightclub owner who’d launched a local record label called Ultrax. Quon needed someone to represent his clients, he told Bowman. He kept talking up a Dallas-born rapper he’d discovered, who went by Vanilla Ice.

Bowman was skeptical but promised to check out some sample tracks. “I’m not gonna say I was crazy about the music,” Bowman told me with a grin. But he thought it would sell. Vanilla Ice became his first client, and Bowman helped negotiate the 1990 release of To the Extreme, which featured the hit “Ice Ice Baby” and became one of the best-selling hip-hop albums of its time.

All of this raised some eyebrows at the firm and attracted the attention of a local reporter. “Entertainment lawyers are about as common in Dallas as snowstorms in August,” began a Parade article about Bowman, published in 1991, just sixteen months after he’d started his tenure at Jackson Walker. In the accompanying photo, Bowman is at his desk, in a dapper pinstripe shirt, several stacks of cassettes to his right, his left elbow propped casually on a boom box. “Even Mr. Bowman admits that an entertainment practice in Dallas—instead of Los Angeles or New York—seemed improbable,” the article continued.

“Deep down,” Bowman told the reporter, “I felt like it could be done.”

Among the readers of that Parade article was the pioneering journalist Marjorie Louis, one of the first Black women newscasters in Dallas’s history, who’d appeared on public television station KERA beginning in the early seventies. Louis clipped the article and mailed it to her daughter Jill, who was fresh out of Harvard Law School and living in Washington, D.C.

Jill typed a note to Bowman, asking if he’d be willing to talk shop the next time she was in town: “I too am an attorney practicing in a ‘not Los Angeles or New York town’ and I am very impressed by your initiative.” He was willing, and she met him at his office. “He looks like a killer record executive,” she recalled. “Like, Berry Gordy has nothing on this man, you know?”

They ended up hanging out every night that week. “My mother is like, ‘So you guys still talking entertainment business?’ ” Jill said. By the time she boarded a plane back to D.C., she’d decided to split with her boyfriend of three years, and not long after, she and Bowman got engaged.

She’d grown up in Dallas and had thought she’d never return. During her years at St. Rita Catholic School, near her family’s home in North Dallas, “I was called the N-word more times than I’ve ever been called before or since,” she said. As an undergrad she’d attended Howard University, the historically Black university in Washington, D.C., where she met and became lifelong friends with future vice president Kamala Harris. “After being raised in Dallas, to no longer be defined by my race, to be defined by the content of my character—that was a liberating and growing experience.”

But Bowman convinced her the city was changing for the better. The couple eventually had two children, Malcolm and Rachel, in 1996 and 1998, respectively. Jill continued to rise through the legal ranks—today she’s a managing partner at the firm Perkins Coie—while Bowman’s career took a different path in 2001, after an old college buddy, Mitchell Ward, asked him to take a look at his struggling company’s balance sheets.

When Bowman’s friends talk about him, they tend to recall instances in which they advised him against something—and then he did it anyway and succeeded.

Bowman concluded that the trucking enterprise, which shipped commercial products across North America, was fundamentally flawed and doomed to bankruptcy. But he came back with an idea: what if they started a new company that inverted the business model? If it rented the rigs rather than owning them, it would be far nimbler and could slash overhead. The strategy worked.

When Bowman’s friends talk about him, they tend to recall instances in which they advised him against something—and then he did it anyway and succeeded. Pertile told me that even among their group of bright, ambitious friends at UT-Austin, Bowman stood out. “If Randy would have had more opportunities growing up, Obama would have been the second Black president,” Pertile said.

By the time Bowman left MW Logistics, in early 2017, the company had enjoyed 49 consecutive quarters of profit. He wasn’t merely cashing out, though. He had long conceived of his life in three parts, carefully mapping his aspirations as if he were planning a scientific expedition. His first goal was simple: to escape poverty by the time he turned 25. The next 25 years, he focused on his career and building a family. Now that he was in his fifties, he turned his attention to helping other families escape poverty.

One afternoon, Bowman invited me to visit his home office, on the second floor of his house, an elegant Spanish colonial nestled in a stand of oaks and set back from a winding two-lane road. His work space is sparsely decorated, the walls adorned with a handful of mementos: a platinum Vanilla Ice record, framed NBA jerseys from athletes Bowman once represented. On a bookshelf is a portrait of his mom, who died a few days before At Last opened.

He hasn’t completely left the business world. He’s on the board of Westwood Holdings Group, a publicly traded wealth-management firm, and he’s an investor in the redevelopment of Red Bird Mall, a once popular South Dallas hangout that had, like many shopping centers of its era, struggled to attract customers. But most of his time is devoted to At Last.

After leaving MW Logistics, he spent a few years engrossed in education research. He narrowed his focus to third to sixth graders because they’re still young enough to mold—plenty of research suggests that intervening early is the most effective way to address poverty and achievement gaps—and he also knew that once students became teenagers, many parents would expect them to go to work after school. Bowman called his program At Last, an acronym for Accessing Transformative Life and Scholastic Tools.

An analytics obsessive, he worked closely with a business management firm to develop a software system to track student progress. And he set out to raise money. For four years, beginning in 2011, he’d served as board chair for the Parkland Health Foundation, which helped expand and modernize Dallas County’s largest safety net hospital, and he drew on those fund-raising connections. He also landed foundation grants and committed money of his own. Bowman’s family remains the largest donor (though he won’t disclose how much they’ve invested). He then commissioned an architecture firm to design the Oak Cliff building, which he calls “house one,” and prioritized domestic warmth. “Our parents have seen enough of their kids or relatives going into institutions,” he said.

In 2019 he made his first hire: Cornell Lacy, a former math teacher who’d grown up in South Dallas and attended public schools. Lacy was hesitant to leave the classroom, but he’d already begun rethinking his role. He’d handed out failing grades to students who routinely missed homework assignments, only to later find out what they were contending with at home. “It really started to make me think about, ‘What is the purpose of the grade I’m giving, and how do I maximize the opportunity for everybody in my class to excel?’ ” Those questions remained foundational when he started designing At Last’s academic programming. Lacy works closely with the students’ teachers to supplement the instruction they’re getting at school; he also uses At Last’s data software to customize the support each kid receives. Lacy is loath to rely too heavily on student grades to gauge their growth, but the gains are notable nonetheless.

From a standing desk in the middle of his office, Bowman opened his laptop and called up a modest chart. When At Last launched, he’d expected that it would take a semester or two for staff to earn the students’ trust and that major academic gains wouldn’t come until the students’ third or fourth semesters. By the fifth and sixth semesters, they would have acquired the study skills and habits to carry them forward after leaving the program.

Success, though, was happening much sooner. The chart showed the semester-by-semester progress of a student who had an average grade of 59 across the four core subjects before coming to At Last. One semester later that number had jumped to a 79. The next slide was even more dramatic: a student went from averaging a 60 overall to a 91 within a few semesters. “I know the backstory,” Bowman said. The child had given up hope and “let go of the rope.” Now they’d gone from probable dropout to someone on track to go to college.

Most of the data revealed more gradual upticks, steady semester-by-semester growth. Bowman showed me one slide in which a student’s grades fell dramatically while attending At Last. There was a backstory here too: the family had been evicted and was without a home, so the kid was habitually absent. “This is one of the disruptions that I wanted At Last to be able to absorb for a family, and we haven’t been able to yet,” he said. He sees this as something that will be less of a challenge when the program is fully operational. As kids begin staying overnight at the dorms in May, At Last can ensure they’re getting to school and back every day.

But they’ll only be doing that through sixth grade. What happens when students graduate from the program and return to potentially disruptive circumstances? Bowman’s belief is that, after four years in At Last, they’ll have developed the necessary tools for academic success. “What I can do is try to better equip them for that journey. I can’t remove them from it.”

Bowman is working to create the infrastructure for long-term support, including a mentoring network with alumni and volunteers. He’s already in talks with schools such as Paul Quinn College, a historically Black school in Oak Cliff. “If you want to go to college, college will be available for you, even if your parents can’t contribute a dime,” he said.

So far, Bowman has been deliberate about growth, insisting on fine-tuning the program’s processes and proving the premise before attempting to replicate it. But it’s already expanding its current location, and he’s explored a handful of other sites in Dallas. He’s also heard from potential partners in multiple Texas cities and other states as far away as Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.

Of course, expansion will come with its own challenges. Experiments such as At Last often work well when they’re small enough to be driven by the passion of a founder—any organization will experience growing pains. Bowman believes the program’s design and its software can be readily adapted in other places.

In the meantime, the vast need weighs on him. “I have to get my child into this program,” parents often tell him.

When it comes to creating a social safety net, Texas has long done the bare minimum: the state refuses to take federal money to give health insurance to millions more residents, is ranked fortieth in school funding, and creates barriers to food assistance. “We as a state make it very difficult for low-income parents to get any benefits,” said Bob Sanborn, head of the Houston-based nonprofit Children at Risk. “But the fact of the matter is, the research is super clear that whenever they get those benefits, they have an easier time being a good parent. There’s less stress on them. They’re able to devote more time to the family. They don’t have to worry as much about having the third job.”

No single nonprofit can compensate for the state’s tight purse strings. But for the students enrolled in At Last, the program appears to give the whole family a boost. Elicha Edwards, the house mom, told me that the support the kids’ mothers get from At Last is comparable to having a stable partner parent, which in turn frees them up to pursue better jobs, potentially creating more permanent stability for their kids. Almost all of them have “advanced themselves careerwise,” she said.

When I visited At Last one afternoon in February, a fifth grader in khaki pants and retro Jordans read aloud from Pete the Cat and His Four Groovy Buttons to a handful of peers arrayed on the living-area couches. Two sisters, just in from their day at school, sidled up to the kitchen counter and snacked from a bowl of sliced strawberries. Nearby, a fourth grader with a blue sweatshirt slung around his neck sat at a desk, a Chromebook propped in front of him.

At Last had recently received a $400,000 grant from the city. And staffers were preparing for their first student to complete the program, a bubbly sixth grader named Endiya. Her mom, Kaliah Reagan, who has another daughter enrolled in the program, had told me it was “the best thing that could’ve ever happened to me and my children.” Endiya wasn’t eager to move on, but Bowman had already found ways to keep her connected: she was interested in becoming a mentor to some of the younger kids.

He confessed that at times the work felt Sisyphean, even as he remained committed to the project’s broader potential.

The program had also experienced setbacks. Earlier that week, Alexis Roberts had called Edwards to tell her she was pulling her sons out of the program. She sounded agitated on the phone, Edwards said. Roberts told her the family needed to move, but she wouldn’t offer much more than that.

Bowman was heartbroken. “It sucks as many ways as it possibly can,” he told me. When the boys first arrived, they were so distrustful that they refused to speak for the first few weeks, their only communication a thumbs-up or thumbs-down. Months later they’d opened up so much, Edwards joked, that the staff sometimes missed the silent treatment.

Whereas a few decades ago Bowman was rubbing shoulders with pop stars and pro athletes, now he spends most evenings with grade schoolers. He confessed that at times the work felt Sisyphean, even as he remained committed to the project’s broader potential. “I will keep pushing this rock as many times as I have to,” he said. And he won’t give up on the Roberts family. He was planning to wait a few months before calling Roberts and trying to persuade her to bring the boys back.

In defining what it would mean for At Last to succeed, Bowman often speaks the language of balance sheets. He always knew the program would sustain at least some attrition, but hearing him agonize over the fate of Roberts’s children, I was reminded of how personal the project was. For all of his preoccupation with data and charts, Bowman’s solution to inadequate educational outcomes was also, at its heart, a wish for every kid to get the thing he never had as a child—the assurance of a stable home.

This article originally appeared in the April 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Problem With Low-Performing Schools? It Isn’t Just the Schools.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Public Schools

- Longreads

- Dallas