One of the awful things about political punditry is that those who offer it are incentivized to act as if every new special election for county fish tank inspector portends some grand change of course in the sweep of history or some key to understanding the future. But while pundits often fixate on the tactics and messaging of campaigns, election results across the board are often shaped more by broad fundamentals than anything candidates did or didn’t do. Simultaneously, each race is sui generis, which makes it hard to draw big conclusions from any one about what national political parties should or shouldn’t do.

The boring truth is that most election results confirm what observers already know. To wit: Tuesday’s elections suggest that the Democratic party is headed toward a bruising in Texas and nationally, that the Bexar County Democratic Party is an unholy mess, and that Austin is not a Republican city. These are not surprising findings. But there are still a few results worth exploring.

Races Across the Country

The most high-profile elections this week weren’t in Texas but in New Jersey and Virginia, where two incumbent Democratic governors tried to hold their seats. Democrats are most likely going to have a bad year in 2022 because a president’s first midterm usually sees his party lose ground across the country. That’s what happened to Democrats in 1994 and 2010, and to Republicans in 2018. In the same way, the New Jersey and Virginia gubernatorial elections, which always take place the year after a presidential election, usually go to the party that doesn’t control the White House. Republican Glenn Youngkin won in Virginia, while Democrat Phil Murphy appears to have barely hung on in New Jersey. Naturally, pundits are falling over themselves to argue that the results affirm their priors—that they’re proof Biden’s agenda is being pushed too fast or not fast enough, that he has moved too far to the left or is being held captive by the middle, etc.

But the conclusions we can draw, especially in regard to Texas, are limited. Virginia Democrats lost ground with nearly every demographic group. Notably, the well-heeled white suburbanites who defected to the Democratic party while Trump was in power did not stay with them when Trump was out. This should concern Texas Democrats a bit. The suburbs of northern Virginia share some similarities with the places in Dallas and Houston where the party made gains in the last few years—and if they revert back to the GOP, the Democrats don’t have a chance of doing much in Texas.

There’s a sliver of hope, perhaps, in the fact that the Texas GOP is qualitatively different from its purple-state counterparts. Youngkin is the kind of Republican they don’t make anymore in Texas—before running for governor, he was a CEO of the Carlyle Group, a private equity company. Business Republicans have been run out of power in Texas, for the most part, and the party’s lawmakers have run hard right in the past year. Maybe that’s enough to continue to alienate independents who didn’t like Trump, but it’s going to be a tough putt.

San Antonio Texas House Seat

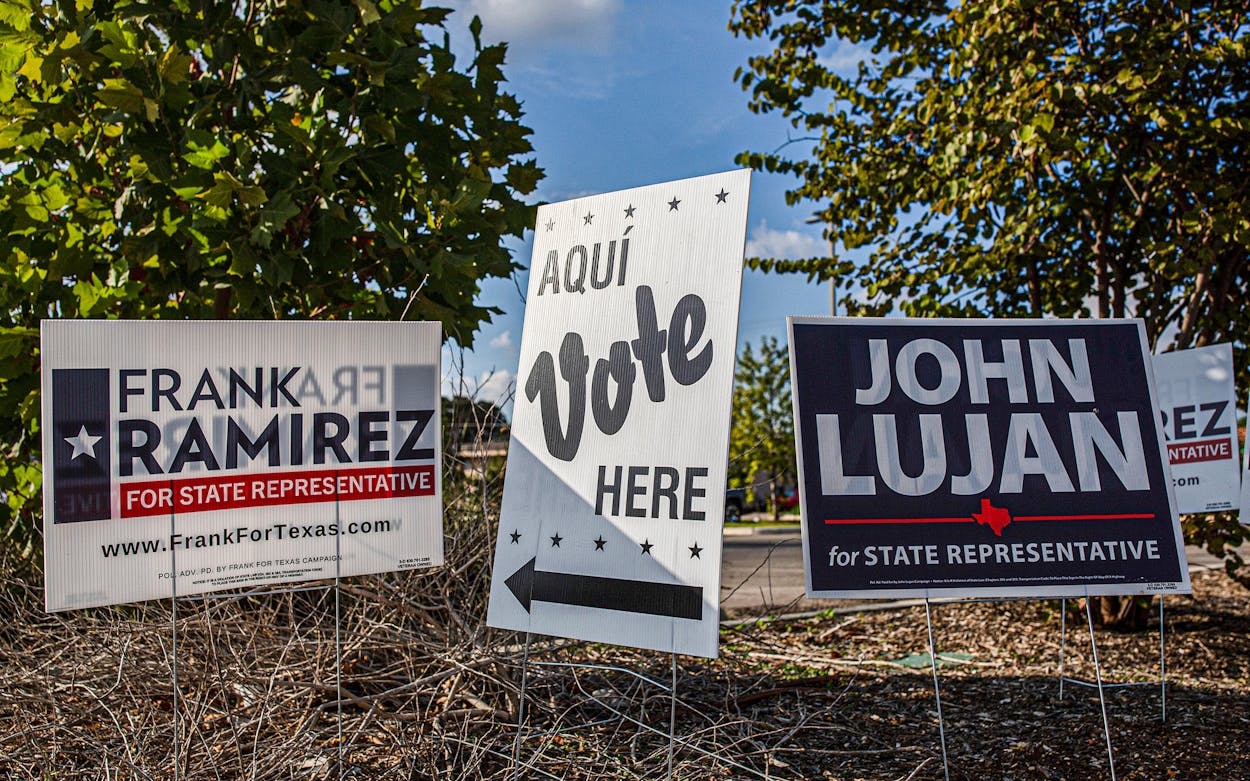

Perhaps the most surprising result of the night in Texas came in San Antonio, where Republican John Lujan won a special election to the Texas House in a district with an ungainly shape that covers much of the south and east of Bexar County. The majority Latino district had gone for Biden by fourteen points. The Associated Republicans of Texas, an important group in the institutional side of the Texas GOP, bragged that Lujan’s victory “marks the beginning of Republicans winning Democrat-held seats in South Texas in the 2022 election cycle.”

But Lujan’s win looks less like a watershed moment when you consider that he previously held the seat, winning it in another low-turnout special election in January 2016 and holding it until that year’s general election, which he lost by ten points. As it happens, San Antonio Democrats have something of a tradition of blowing low-turnout off-year elections in a maximally embarrassing way. They can’t get the vote out and they sometimes field terrible candidates. (When Lujan won the seat the first time, the head of a prominent Democratic messaging outfit, Progress Texas, tweeted that the difference between Lujan and his opponent was the difference between “cat shit and dog shit.”) This congenital humiliation has not proved a good indicator of what’s going to happen in the general election—like Lujan in 2016, Pete Flores, from just south of San Antonio, won a special election, earning a Senate seat in 2018, before losing his next race—although the new House District 118, resulting from the gerrymander recently passed by the Legislature, should be a lot easier for Lujan to hold.

Refunding the Police in Austin

In Austin, a proposition to “refund” the police force failed by an overwhelming margin, 68 to 32. In 2020, the Austin City Council cut the police budget by one third—largely by reshuffling some offices and responsibilities, including forensic sciences and victim’s services, into other city departments. A group called Save Austin Now, riding high from its reinstatement of the city’s anti-camping ordinance earlier this year, gathered signatures for a strangely worded ballot measure to hire hundreds of new police officers—arguing that the recent rise in crime was a result of the city council’s budgeting process. Critics said the proposition would monopolize and devastate the city’s budget, already under strain thanks to the Legislature. The fight won national attention as a referendum on police reform amid rising crime. Voters threw it in the trash, and Save Austin Now’s many foes are taking a victory lap. The group will be back, of course, as long as it can get donors to grease the wheels.

The real shame here is that 2021 was a crucial year in the state’s capital city, which is experiencing one of the most frenzied periods of growth in its history, but politicians in the city were largely consumed by completely irrelevant debates. Save Austin Now’s supporters on social media often complain that the city is becoming San Francisco, or Seattle, or Portland, by which they mean that Austin is becoming a ruined town, undone by limousine liberals in city government who are afraid to restore order. It’s true that Austin faces many of the same problems as San Francisco or Seattle. The cost of housing and the cost of living are skyrocketing, as a flood of new residents transforms neighborhoods. Strained city services, endless sprawl, and an increase in homelessness are the results. The main thing Austin could do to mitigate those problems is aggressively upzone large areas of town—but that isn’t a debate that can be had along partisan lines. So the city is stuck, as nearly everyone else is, arguing about nonsense.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy