Dr. Brené Brown was at a low point in her life the first time she heard Willie Nelson’s cover of “Amazing Grace.” It was in the early 2000s, a period she has famously referred to as a “breakdown/spiritual awakening,” and she was walking through her Houston neighborhood listening to various versions of the song on her iPod.

When Willie’s rendition came on, which he’d originally recorded for his 1976 album The Sound in Your Mind, she suddenly heard the song differently. She replayed it over and over so the message could sink in. “It’s not hyperbole to say that, in a very weird way,” she says, “Willie’s version of ‘Amazing Grace’ was completely transformative for me.”

Subscribe

(Read a transcript of this episode below.)

In this week’s episode of One by Willie, Brown describes her feelings that moment, the deeper understanding of the song that followed, and the way that understanding informed her own teaching on vulnerability, shame, and empathy. We also discuss the song’s history; her lifelong love of Willie; the concepts of faith, grace, and acceptance, more generally; and another, even more powerful, performance of “Amazing Grace.”

We’ve created an Apple Music playlist for this series that we’ll add to with each episode we publish. And if you like the show, please subscribe and drop us a rating on Apple Podcasts or wherever you get your podcasts.

One by Willie is produced and engineered by Brian Standefer, with audio editing by Jackie Ibarra and production by Patrick Michels. Our executive producer is Megan Creydt. Graphic design is by Emily Kimbro and Victoria Millner.

Transcript

John Spong (voice-over): Hey there, I’m John Spong with Texas Monthly magazine, and this is One By Willie, a podcast in which I talk each week to one notable Willie Nelson fan about one Willie song that they really love. The show is brought to you by Still Austin craft whiskey. This week, Dr. Brené Brown, the internationally regarded researcher, storyteller, and author, who built her career studying courage, vulnerability, shame, and empathy, is going to talk about Willie’s sublime 1976 version of “Amazing Grace.”

Now, I should note that Dr. Brown’s fans and friends just call her Brené, and I suspect they shorthand that list of heady job descriptions to simply: inspiration. Well, for my money, that’s exactly what she’s fixing to do with us. Inspire. She’s going to describe how listening to Willie’s version of “Amazing Grace” completely transformed her life, helping her finally understand how to live with fear and uncertainty, before then getting into the way that music connected Willie and sister Bobbie, and really all of us if we’ll let it. And then she’s going to go even deeper, into the concept of faith and grace itself. Oh and we’ll also be discussing, at the close of the episode, the single most powerful performance of “Amazing Grace” either one of us has ever witnessed. So let’s do it.

John Spong: Well, so to start, we’ve opened pretty much every show the same way, which is with this kind of flippant, facetious question from me, where I say, “What’s so cool about song X?” And so it’s like, “Hi, Sheryl Crow. It’s me, John. What’s so cool about ‘Crazy?’”

You can’t do that with “Amazing Grace,” with the song you chose. It means something more. It’s qualitatively different, what this song means. What I’d like to start with is when I asked you to talk with me about Willie Nelson, you said you wanted to talk about this song. How come?

Brené Brown: God dang, I can’t cry this early. I’ve got to cry later. Dang it! It’s not hyperbole to say that, in a very weird way, Willie’s version of “Amazing Grace” was completely transformative for me. It actually stopped me dead in my tracks. I was—how old was I in 2000? I’m doing the math real quick. Yeah, that’s right. I was 41, and I was going through a really, pretty serious kind of midlife unraveling. It was just a shit show for me. I call it a “breakdown/spiritual awakening,” basically because my therapist forced me to add “spiritual awakening” to it. I was in this period of time where I was obsessively listening to “Amazing Grace” and “Hallelujah.”

John Spong: Ah, yeah.

Brené Brown: Yeah. I was collecting every version of them that I could by the kind of artists that I really love. And those are—I like my spirituality with honky-tonk rising. And so I’m not interested in clean theology, because I just think it’s an oxymoron in some way. And so I was listening to, I never know how you pronounce her name, Ani DiFranco.

John Spong: That’s how I say it.

Brené Brown: Yeah. Singing “Amazing Grace.” I was listening to . . . it’s where I first got introduced to Brandi Carlile singing “Hallelujah,” from many years before she was well known. I’ve always been a Willie fan, fifth-generation Texan, you know, birthright.

And I had a playlist on my iPod that I called “My God on the iPod.” Yeah, it was terrible. And it was my kind of religion. It was like the Blind Boys of Alabama, Loretta Lynn “How Great Thou Art.” And so I downloaded “Amazing Grace” by Willie. And the context of the first time I listened to it—I was walking through my neighborhood in Houston, and I was in a real crisis of confidence because I had been asked to join the board of the Nobel Women’s Initiative. And this was an initiative where every living female Peace Prize recipient came together and to shine a light on women activists doing on-the-ground, important social justice work.

Well I, at the time, was teaching at the University of Houston with Jodi Williams, who had won the Nobel Peace Prize for her work on landmines. She and I cotaught a class together on social work and social justice. I had been invited to go to a Nobel Women’s Initiative Women in the Middle East Peace Conference in Galway, Ireland.

I was really excited, except that several of the women attending had death-threats issued against them—Shirin Ebadi and people that were really doing this incredible work. And I had a one-year old and a seven-year old, and I’m a scared person a lot. I used to be much more fearful all the time, about everything.

Part of my spiritual awakening/breakdown was, “God, I’ve got to stop being so afraid. I got to stop getting on a plane and telling Steve, ‘Listen, the chances of me making [it] back are slim. Here’s a list of the people you could marry, and here’s the people that you damn sure better not marry when I die.'”

I was losing my mind a little bit. So I had to make the decision about this conference. And I grabbed my iPod and my headphones, and I went to my playlist, my iGod playlist, and Willie’s “Amazing Grace” came on. Well, up until that moment, I thought the lyric was, “Twas grace that taught my heart to feel.”

But when Willie sang it—and remember I had 20 versions of this already that I’d been listening to for a year—he’s saying, “Twas grace that taught my heart to fear,” not “feel,” “And grace, my fears relieved.” I’m walking through my neighborhood, and I just stop. And I’m like, “What the hell?” And I played it back. And again, “Grace that taught my heart to fear . . . Grace that taught my heart to fear . . . Grace that taught my heart to fear.”

And I couldn’t believe it. I was really shocked that it wasn’t “feel.” And then all of a sudden it dawned on me that I didn’t know how to be afraid. I don’t know how to be afraid. And that’s the grace part. And then it was so weird because I went back immediately and listened to all the other versions, and I’m like, “Of course they’re saying ‘fear.’ Grace taught my heart how to fear—and fears, it released.”

And in that moment— I’m a pretty deeply spiritual person, Episcopalian by practice—in practice, I’m a member of the Episcopal Church. In my heart, I’m probably a mystic Catholic, and in my head, I’m probably a contemplative-theologian person.

Somehow that all makes sense to me. That’s my Holy Trinity anyway. That and Lake Travis. And so I end up going. I end up saying, “You know what? I’m going on this trip. I can be afraid and go at the same time. Both things can be true. I just need grace. Both things can be true. I can be afraid and go—I just need this ‘Amazing Grace’ that Willie’s talking about here.”

So I go to the Barnes & Noble by my house, and I just grab a journal, and I get to Galway. It’s my first morning there. I say, “I am going to go pray at the edge of the water.” I climb this grassy hill, and I’m looking for somewhere to sit, and there’s fifty rocks, shaped like a heart. I don’t know, I mean it’s just if I explain it wouldn’t be real. And so I go like—so I sit on it, and then I listen to Willie sing ”Amazing Grace.” It’s going to get weirder. And then I look out, and I see the Aran Islands. I open my journal, which I just picked because I love the color forest green—but there’s a Celtic cross on the front of it that I didn’t even see when I bought it. And somehow I hit “shuffle” on my iPod, and the next song that comes on is “Into the Mystic,” by Van Morrison. I’m like, “Okay, I get it.” [Laughs]

John Spong: It’s like, that couldn’t happen right now during a writer’s strike.

Brené Brown: Yeah. No, no. If someone wrote that into a movie, I’d be so pissed off. I’d be like, “Oh, yeah, like that happens.”

But to this day, I still listen to this specific version of “Amazing Grace” by Willie every time I’m afraid. So every flight I take, I always feel like every time I get on a plane, and I do that often, I feel like I’m cheating death. But I just listen to it. And I’m like, “Okay.” I’m on the plane. I can be afraid and still be here, as long as Willie’s here saying, “It’s all right.” Yeah. That’s my story.

John Spong: I am a fan of that story. Will you listen to “Amazing Grace” with me, right now?

Brené Brown: Oh man, I will. Yeah, I will. I’ve never listened to it with anyone before.

John Spong: Uh-huh!

Brené Brown: Uh-huh.

John Spong: Look at me!

Brené Brown: Look at you.

John Spong: This is fantastic. Thank you.

Brené Brown: Go.

[Willie Nelson singing “Amazing Grace”]

Brené Brown: No words.

John Spong: Yeah.

Brené Brown: Yeah. It’s just . . . I don’t know. It’s like a direct line.

John Spong: Yeah.

Brené Brown: Do you think that’s Bobbie on the piano?

John Spong: Without question. Without question. Yeah. That’s Bobbie. And it’s a song that they had been playing together since they knew how to do anything. I cannot imagine there’s a time in either of their lives—and of course, she’s not around anymore—where they can remember learning that song and not knowing that song.

Brené Brown: Yeah. There’s just something that’s so truthful about his . . . how he brings . . . and really, it makes sense to me that it’s Bobbie. It’s really how they bring . . . to me, that song feels like it’s embodied by them in an important way. It’s just real. And it’s . . . I don’t know. I don’t like that song when it’s super-perfect. It bugs me.

John Spong: Well, that’s the thing. With the two of them in particular, do you know much about their childhood?

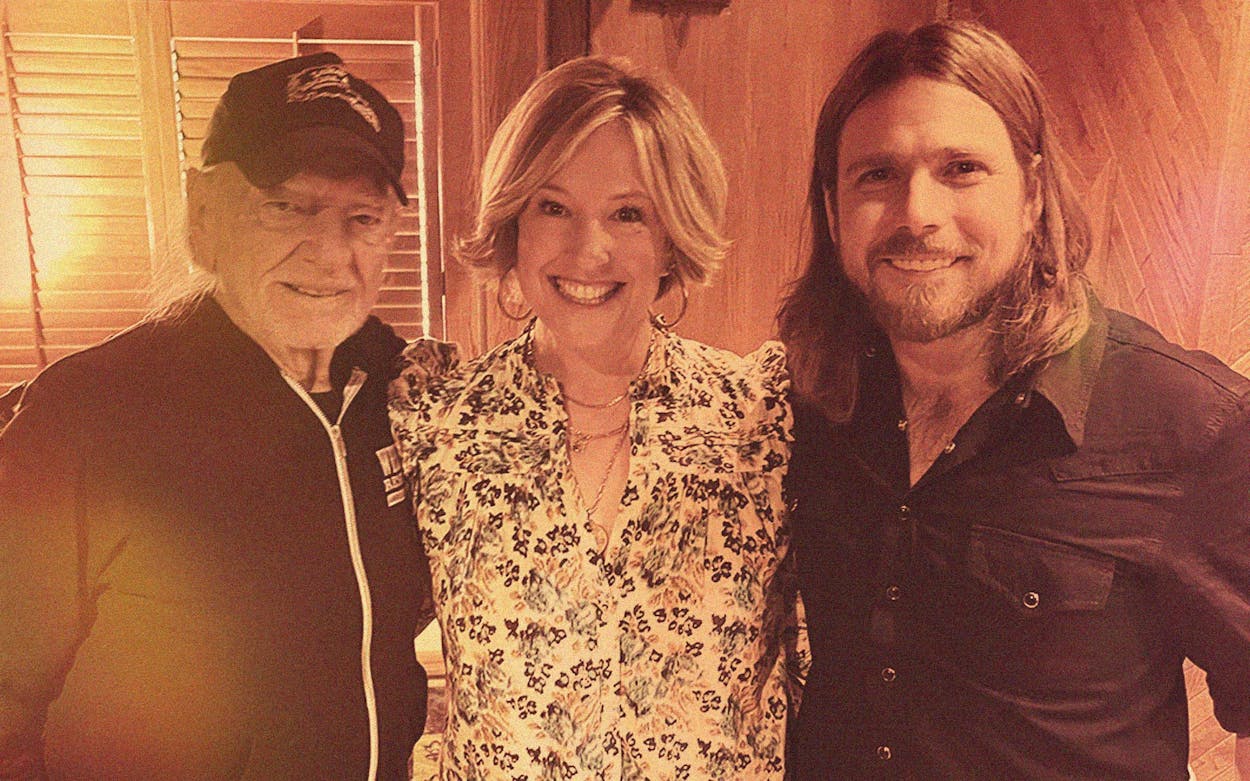

Brené Brown: I do, only because I’ve read their kids’ books; I’ve read Bobbie’s book. I’ve read Willie’s book. I’ve read their kids’ book together. And then I interviewed Willie and Lucas a year and a half ago or so. And so we talked a lot about . . . and then I have a framed picture in my house of . . . Bobbie’s at the piano with that satin UT jacket on, and Willie’s sitting next to her.

I think maybe they can embody the music because they lived it in a way. I always think about the story he tells, and you could probably know it better than I do, about singing and trying to make a living in church or the honky-tonk. I don’t think those are mutually exclusive choices.

John Spong: One of my very favorite words is “salvific.” What is that—the adjective form for salvation?

Brené Brown: I don’t know.

John Spong: Yeah. Yeah. This smart preacher lady taught me that word. That’s what music was for them. They’re little, and right after Willie’s born, their mom splits. And then they’re with the grandparents, but then the dad splits almost right after that. And the grandmother’s teaching Bobbie piano, and Willie wants to play with her. Grandpa, who is their dad, gives Willie a guitar, his first guitar for Christmas when he is six.

And then Granddad dies a few months later. And this is the height of the Depression in, like, Dust Bowl, outside-of-Waco, Abbott, Texas. The only time they ever felt safe was when they were playing music together. The only time the world was locked out was when Bobbie and Willie are playing music together.

And it’s these gospel songs. You know? And so, whatever “Amazing Grace” has meant to people through the decades, and whatever it started to mean during the civil rights movement, it’s the most basic thing in the world to Willie. Playing music with Bobbie was how he kept himself alive. Anytime they go back, so when they go into the studio in Garland to record this in ’76, or whatever it was, that’s the place they’re going back to.

Brené Brown: You can feel it.

John Spong: That’s why I love that you keyed on her piano, because that’s what we’re hearing. That’s what we’re hearing.

Brené Brown: Yeah. You don’t just hear grace, you feel grace.

John Spong: Yes. Yeah.

Brené Brown: That’s different. I’ll tell you, I don’t know if you know this term, you probably do, but that song is a “thin place” for me.

John Spong: Yes.

Brené Brown: It’s a thin place for me. It’s where the space between me and God becomes . . . the proximity just shrinks, and I’m there.

[Willie Nelson singing “Amazing Grace”]

John Spong: Do you know much about how this song was written, the origin story of this song?

Brené Brown: I thought I did and then I read something when I was prepping for this, that that wasn’t true. I’m going to let you tell me the origin story for it, because I think there’s a lot of mythology around it.

John Spong: Well, if I’ve read right, it’s written by an Anglican priest—your people, or our people, actually. John Newton. But the deal is that, so John Newton, this is the mid-1700s, was a rotten person by all accounts. He was involved in the slave trade. And not involved like he worked on a slave ship; he’d get off the ship and go find folks and decide who was going to be a better sale.

Brené Brown: Jesus Christ.

John Spong: Just despicable. But he also . . . notably, this is clearly before he joins the clergy, I hope that’s clear. He did not believe in God and very proudly didn’t believe in God. He liked to mess with people. So he liked to spout things very loudly and proudly that a believer would consider blasphemous, because he knew it would mess with him. He had a lot of fun with stuff like that.

And so then he’s on a ship—and so you had a moment in Galway—he was on a ship off of Donegal just north of there. And there’s this terrible storm. He’s convinced the ship’s going down. He’s convinced he’s going to die, and he cries out, “Oh, Lord, have mercy on me!” And that’s his conversion moment.

He continues in the slave trade for a bit; ends up joining the clergy. And eventually becomes a staunch and significant abolitionist. He finally understands that what he had done was unforgivable. In the meantime, he’s got a small church in Olney, wherever that is. And he starts writing poetry—psalms, effectively. So he writes this as a poem that is recited, I think, in 1773 for the first time, and then it’s published in 1778. People start attaching music to it; it makes its way across the pond. It had twenty different melodies attached.

Well, it’s about to get really cool. I think 1835 or so, it gets the melody that we know, that’s so familiar to us, that’s the famous one, published in a hymnal in 1850 with this melody. Here is the thing: There’s the verse in there, and we were just listening, “When we’ve been here 10,000 years, bright shining as the sun.” He didn’t write that. Those words first appeared in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, because slaves, enslaved people, had picked up on this song. And it started mattering to them. They added in that verse. It’s actually from a completely different hymn, old hymn. And they passed it down through their oral tradition. And it’s only when Uncle Tom’s Cabin is written that we get that magical verse, which might be my favorite part of the song.

Brené Brown: That’s my favorite part of the song.

John Spong: It’s like when you talked about the line that got you when you were listening to Willie, “It was grace that taught my heart to fear, and fear that grace relieved.” There’s almost a contradiction in terms there. Grace instilled fear, but expelled fear? Wait. That is grace. There’s a reconciliation there of two things that don’t necessarily, at least for me, make sense. But then also that this song is grace at work. Its cowriters were a slave-trader and enslaved people?

Brené Brown: I had no idea.

John Spong: Isn’t that something? Isn’t that something?

Brené Brown: For me, when I read that line, “It was grace that taught my heart to fear, and grace my fears relieved.” Like, I think it is grace that taught me how to be afraid, how to be scared, that it’s okay to be scared.

John Spong: Yeah. You’re living with an imperfection.

Brené Brown: Yeah. You’re living with an imperfection. And it’s human. And it taught me how to be afraid without working my s— out on other people. This is how to be afraid. It’s how to be vulnerable, really.

John Spong: Yeah.

Brené Brown: And that’s my work. I think when a lot of us go into fear, we go into blaming, shaming; armor comes up, we diminish people to feel bigger and less afraid. And I think . . . yeah, it’s probably why this song is so pure God for me, is because I can’t find the willingness to straddle the tension of paradox, in the church. But yet, it defines my experience of God. So then church, the man- . . . very specific, man-made part of church, sells itself by reconciling paradoxes, where I feel like God and to some degree, Willie Nelson’s “Amazing Grace,” just jumps right into the paradox and says, “I don’t need to figure this s— out. Both these things can be true. If it makes you uncomfortable, too bad.” Do you know what I mean? I sound crazy. I don’t know. I don’t mean to sound crazy.

[Willie Nelson singing “Amazing Grace”]

John Spong: How did he come to matter to you so much? And please don’t leave out Curly.

Brené Brown: Oh, God! Well, my grandmother was my person. Ellen. She lived on [the] south side of San Antonio. Her husband, Curly, was a forklift driver at Pearl Brewery, which is now a fancy shop-and-dine location.

John Spong: Oh yeah. Right.

Brené Brown: Yeah, yeah. Back then, I assure you it was not. And so I spent every summer with Meemaw and Curly. And Curly did two things—three things, I guess. He went to work at Pearl, he sat in his recliner and listened to KBUC, and he slept.

And so my first . . . the first people I fell in love with was Willie Nelson on KBUC. And then Meemaw, my grandmother, Ellen, would always have a cigarette in her mouth. She’d wear a cigarette and a housecoat and square-toed cowboy boots. She would always do this thing with her cigarette, with her hand, “Ooh, I love this piece. Listen . . .” and it’d always be Willie Nelson or Loretta Lynn, Johnny Cash. Oh, and then her favorite, Charley Pride, was just— she was obsessed.

John Spong: You’ve ticked off so many artists that you lean on. Music matters to you in a very special way. And so much of what you talk about is about connection. And music creates these very . . . when you talked at the National Cathedral, you talked—ah, shoot! Where’d I put it? The three things you go to in church: singing with strangers, passing the peace with people you maybe don’t want anything to do with the rest of the week, and breaking bread with people. You might as well be describing a Willie Nelson show.

Brené Brown: Yes. No, there’s no difference really. I think it goes back to this term, which I love: “collective effervescence.” This thing that they were . . . French philosophers studied, they saw it at first in churches. They thought it was dangerous and magical, and they weren’t sure about what it meant and how it worked. When you try to create it, it’s very hard to create it. But when you bring humans together and there’s music and there’s shared communion, whether it’s actual communion or just communion, and that whole idea of collective effervescence . . . music is really . . . I mean, music by myself is important to me.

I was in the car a couple of days ago with my son, who’s getting ready to be a senior in high school. And I was listening to my ’70s playlist, and Ambrosia came on, and he knew every word. And I was, like, all puffy and proud. And then I’ll get in his truck, and we’ll sing along to “Thunderstruck,” by AC/DC.

It doesn’t matter to me, and I’m not . . . it’s about . . . if I’m in the car with one of my kids, and we’re singing the same song, that s— is holy. That’s holy. That’s a holy moment. Music really, really matters to me. I think—you know, I’ve spent my whole career studying connection, love, vulnerability, belonging, shame. You could unleash every researcher in the world, and no one’s going to get there as fast or as accurately as the poets and the musicians and the writers.

When I was writing—what book was it? Braving the Wilderness, which was about belonging. I went all over the country, actually all over the world, and I ended that talk, during the book tour, with an arena-wide singalong of Townes Van Zandt. “If You Needed Me.”

[Townes Van Zandt singing “If I Needed You”]

Brené Brown: And just watching these people from all over, holding hands or swaying or arms wrapped around each other singing, “If you needed me, I would come to you. I would come to you, for to ease your pain.” There’s power in that.

John Spong: I’m so thrilled we got there because there’s a darkness in Townes’s music. I’ve always enjoyed using the word “wallow” to describe what I’m doing when I put it on. But actually listening to you and thinking about this stuff with that book in particular, I’m not going to use the word “wallow” anymore. I don’t think it’s a problem, but it’s not actually what we’re doing when we do that. And you summed it up perfectly. Where is it—you said about these sad songs, these really difficult dark songs, “When we hear someone else sing about jagged edges of heartache, we know we aren’t alone in our pain.” Boom! There’s the connection you’re talking about.

Brené Brown: Yeah. Yeah. Townes’s life was, I think, particularly . . . there’s a tragic note, a real tragic note, a tragic story in his life, about mental illness and addiction. But show me a person who hasn’t experienced addiction or mental health or been affected by it because someone they love has struggled with it, and I’ll show you a liar, just statistically.

No one rides for free around those issues. I don’t know if . . . I’m sure you’ve seen this, but there’s a video of Townes playing. And there’s a woman cleaning the kitchen while he is playing it, and there’s a man sitting in the corner. Do you know what I’m talking about?

John Spong: Yeah. I’m very embarrassed that I can’t remember that man’s name because it was Uncle . . . and he was a blacksmith. And they lived in . . . that house was where MoPac is now in Austin. That was Clarksville, which was the historically Black community, until the Austin powers decided that that was going to be nice real estate, and we needed to move the Black folks over to the east side in the twenties or thirties. But that was where he lived, and that’s where Townes lived, because that’s where Townes could afford to live in the early ’70s. The clip is in the movie Heartworn Highways. I think the song is “Looking Around” . . . “Waiting Around to Die.”

Brené Brown: “Waiting Around to Die.” That’s the song.

John Spong: The old man just starts weeping, and it is not put on.

Brené Brown: No, no. Oh my God! I have goosebumps all over. Holy s—! That’s the documentary. That’s the song . . . I just listened to that song yesterday actually. When I saw him weeping, I saw two things. I saw grief, and I saw connection. Connection to know I’m not alone, to know that this emotion that’s welled up in every cell of my being, that you can put words to it and music to it and convey the power of it. And we can be in communion. Come on. That’s everything.

[Townes Van Zandt singing “If I Needed You,” followed by audience at Brené Brown talk singing along to “If I Needed You”]

John Spong: Can I tell you the shortest story that I think you’ll dig?

Brené Brown: Yeah.

John Spong: About how I came to understand grace? Or my personal understanding of grace?

Brené Brown: Yeah, please. I’d love it.

John Spong: My uncle was an Episcopal bishop. And so when I listened to you interview, on your podcast, Bishop Curry, Michael Curry, it doesn’t remind me of my uncle—because it’s Bishop Curry—but to be that intelligent and that relatable . . . There’s so much love inside that dude . . . that he’s leading with that. That that’s the takeaway in spite of these other things. But also, and I’ve heard him preach—man, there’s nothing like somebody who can preach, who can really preach.

I saw my uncle perform one wedding, a few years ago. It was in New Orleans. My stepsister was getting married and my uncle was good at this stuff. And so, at one point he steps down from the altar—and maybe that’s right after we pass the peace—he steps down from the altar and he says, “Okay, you guys are a community, you’re family, and we’ve come here together because Ashley and Mark are fixing to get married. They’re going to need your help. There are people here who . . . Because being married is not easy. As excited as they are today, it’s not going to be like this the rest of the way. We’ve got people here who have been married for many years. We’ve got people here who have been married many times, but they need your advice. And so I’m going to ask you to give them some advice. But a rule: It’s got to be in one word. I would like you to give them one word of advice. Just go.” And so there’s an awkward pause.

And then finally somebody says “love.” And my uncle says, “That’s good. That’s right. Love.” And somebody else—”but more.” And somebody else says “empathy.” My uncle says, “That’s good.” Somebody says “humor”. . . “patience”. . . “sympathy”. . . “togetherness”. . . and all this stuff. And finally somebody says “grace.” And my uncle says, “That’s what I’m looking for. Everything you guys just said is contained within ‘grace.’ Because Ashley, there’s going to be times when he drives you crazy. And Mark, there are going to be times when she drives you crazy. And simply put, there are going to be times when you let each other down. When that happens, you need to know that the other is still going to be there after that happens. That is grace. That’s what you guys have got to do for each other.” I got it. I finally understood it.

Brené Brown: It really does. It is really the container for all of the other things. I was thinking about what word would I have said? And probably thirty years into my marriage, I would’ve said “forgiveness,” probably. But that too would’ve been held by grace. God, that’s really good. I get it. Yeah.

John Spong: Yeah.

Brené Brown: Small word . . . big, big idea.

[Willie Nelson singing “Amazing Grace”]

John Spong: You spoke earlier about “thin places,” and when you talked to Bishop Curry about that, I loved the way he put it. He said, “A thin place is a moment where the present intersects with eternity.”

Brené Brown: Woo-hoo! I’ve got goosebumps.

John Spong: Isn’t that good? Well, you got it out of him. Hell!

Brené Brown: No, but that’s good. I’ve been trying to think a lot about . . . again, I’m like ass-high in Richard Rohr books right now, so I am so hard to be around. I am really on that “second half of life” theology. But do you know Richard Rohr’s work?

John Spong: Un-uh. Hit me!

Brené Brown: Oh my God. I’m going to send you some books. As soon as we get off here, I’m going to send you some books.

John Spong: Please.

Brené Brown: He’s probably one of my favorite living theologians. I read a lot of Thomas Burton and I read a lot . . . but just his work is incredible to me. He’s just this incredibly thoughtful, contemplative—kind of talks a lot about the cosmic Jesus, talks about the failures of the church to stay focused on healing. I asked him questions about the LGBTQA community and he’s like, “Oh my God, how dare you tell God who to love?” He’s just an incredible, to me, theologian.

But I just wrote the forward for a rerelease of one of his books, and he writes a lot about the twelve steps and spirituality. And I’ve been sober for . . . just this month, I just celebrated 27 years. So, a long time.

John Spong: Hey, congrats!

Brené Brown: Yeah, thanks. But when you were talking about Bishop Curry’s definition of a “thin place,” where present meets eternity, when I was reading this latest book, I remember thinking, I think there comes a point in our lives, at least for those of us on a spiritual journey, and not everybody is, and that’s cool.

But for me, rather than jetting out of my life and visiting a thin place and coming back into, like, the real world of get-shit-done, the to-do list, and all that other stuff, I think you can get to a point, at least I think I am at a point where I want to set up shop not in this world and visit that world and a thin place, but I want to spend more time inside of the place in me where God lives.

I think for me, and it’s not just “Amazing Grace” by Willie, but the whole group of people, Johnny Cash singing “I Shall Not Be Moved.” Loretta Lynn, “How Great Thou Art.” I think that those are signposts for me, for the way home for me. They’re just studded with struggle and heartache and pain and addiction. I don’t want a hymn from someone who’s never passed out in a bar. I’m just not interested. I don’t know why. It’s a terrible bar. It’s a terrible threshold. I just think that’s some trench religion for me.

John Spong: Yeah. Well, so, along those lines, great hymns sung in a powerful way, can I ask about an event that I suspect you would describe as a thin place?

Brené Brown: Sure.

John Spong: Can you talk about when President Obama sang “Amazing Grace” in Charleston?

Brené Brown: I think the fact that we’re both getting weepy about that means the answer’s probably no. I probably can’t talk about it, but I can . . . what I can say, all I can say about it, is just like music can unite, it can heal. But I probably can’t talk about it because I’m so f—ing angry about the pain in our state, and the policies and the decisions that people are making that in no way reflect who we are. I probably can’t.

John Spong: It was—everybody knows what we’re talking about. Nine people killed just by hate. And talk about vulnerability—I mean, they were in prayer, when it happened. And it was the result of a problem that you just described, that those people had been dealing with their entire lives, and so many people weren’t even listening to them, and then that happened.

And it doesn’t matter if someone agrees with Obama’s politics, you can not like him because of his politics, you can not like him just because you don’t like him. But what he did that day, there was no place else for him to turn but that song. When everybody sang it together—and actually, I’ll push back. I don’t know that anyone healed that day. It’s like the Willie song: “It’s not something you get over, it’s something you get through.” That song didn’t take care of anything. But in that moment, people were holding hands, literally and figuratively. That is not something Obama did. That is something that that song does. It’s something that grace does.

Brené Brown: It is something that grace does. And man, what an example of ‘grace is courageous.’ I’m saying this as someone who studies courage. Grace is not for the faint of heart. Grace takes—I mean, this is, again, Richard Rohr—grace takes so much courage to accept. I am trapped in relentless grace.

And God, that pisses me off because I’m a meritocracy girl, living in a grace-filled world. I don’t like it. But grace is courage. And that moment of . . . and “healing” was . . . I’m glad you pushed back because “healing” is not the right word, but what is the word I’m looking for? Maybe “communion” is the right word. Maybe to go back with that, like you’re not alone in this. And prayer and dropping to our collective knees—and dropping to your knees takes courage. Yeah. It’s brave to accept it, it’s brave to give it.

[Barack Obama and congregation singing “Amazing Grace”]

John Spong: And so for . . . anytime Willie does a song, everybody says that’s his. We did a podcast interview with Shakey Graves, and he talked about “Always On My Mind,” which everybody thought was an Elvis song until Willie did it. Now it’s a Willie song.

But Willie doesn’t own “Amazing Grace,” and he wouldn’t say he did. Everybody’s tapping . . . when they sing that song . . . Judy Collins, who had the big hit with it, said, “When I sing that song, I can hear everybody that ever sang it singing with me.”

Brené Brown: Oh, God! That’s so beautiful. Yeah, there is a very . . . that’s why I was asking about Bobbie. There’s a very looming sense of deference when Willie sings that song.

John Spong: Yeah.

Brené Brown: Do you know what I mean? Like a bow . . .

John Spong: Yeah.

Brené Brown: . . . to the topic, and to the history, and to everyone else who’s had the courage to sing it, sing along with it, accept it, pray for it, shove it out away from them, myself included. But yeah, and I don’t . . . It was really weird when your team came back and said, “Which version?” I don’t think I knew there was more than one version. I think y’all sent me some links, and I played the one that it wasn’t. I was like, “No, that’s not it.” And then I started to doubt myself that it existed. Like, “No, and it’s . . .” And you can hear Trigger.

John Spong: Yes.

Brené Brown: You can really hear Trigger. You can really hear Trigger. And you can really hear the keys of an old piano.

John Spong: Yep.

Brené Brown: You can’t play that s— on a new piano. It was just . . . yeah. It’s my song. I bet I listen to it, still . . . I bet I still listen to it—and that was fifteen years ago—I bet I still listen to it, by necessity, two or three times a week.

John Spong: I’m so grateful to you for talking to me about all this stuff.

Brené Brown: Me too.

John Spong: Thank you.

John Spong (voice-over): All right, Willie fans, that was Brené Brown talking about “Amazing Grace.” A huge thanks to her for coming on the show, a big thanks to our sponsor, Still Austin craft whiskey, and a big thanks to you for tuning in. If you dig the show, please subscribe, maybe tell a couple friends, and visit our page at Apple Podcasts and give us some stars. And please also check out our One by Willie playlist over at Apple Music.

Oh, and be sure to tune in next week to hear Willie’s youngest son, Micah Nelson, talking about one of those Willie songs that seems to have kind of become a personal mission statement for him: “Still Is Still Moving to Me.” We’ll see you guys next week.