This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

At a time when many us have come to think that switching on the playback mode of the Betamax is a serious test of manual dexterity, a rapidly growing throng of professional artisans are giving new life to some almost forgotten handicrafts. They talk about a crafts revival, and their movement is dedicated to the proposition that the things around us can be both beautiful as art and useful in everyday life. These craftspeople are keeping the old, reliable opposable thumb in business, and they are subtly changing our surroundings while considerably altering some of the ways in which we look at art.

The current crafts revival germinated in California in the fifties, led by people like ceramicist Peter Voulkos, who blazed a trail into major museum collections. This movement, stoked by the back-to-the-earth mood of the sixties, has now become nationwide. Here in Texas, where the traditional tradesmen of a rural society—bootmakers, blacksmiths, and saddlemakers—haven’t entirely disappeared, the ground swell of new crafts activity has been particularly strong. But most modern Texas craftspeople aren’t clinging to nostalgia, and much of their work is as up-to-date as any contemporary painting or sculpture.

The idea of combining art with everyday articles is hardly revolutionary. For most of history, art has carried water as pots, gone into battle as armor, and kept drafts off people as tapestries, rugs, and embroidered fabrics. Art went everywhere, and the idea that it shouldn’t be useful was never considered. Only since the industrial revolution, with its proliferation of things both utilitarian and ugly, have artists avoided the stigma of producing practical items. Most modern attempts at bridging this supposed gap between art and life have ranged from the futile to the ridiculous. Chairs designed to follow the angles of a painting by Mondrian, for example, were often more torturous than the rack, and a sip from a Constructivist teacup could frequently end up on the shirt. Meanwhile, respect for traditional crafts reached its nadir, and museums that celebrated the aesthetic potential of crumpled automobile fenders, punctured inner tubes, and piles of bricks generally looked with disdain on the work of contemporary artisans. That prejudice is eroding now, but serious artisans still have to contend with the negative image created by the recent proliferation of amateur macrame addicts and street vendors who have mastered the made-in-Taiwan look.

In this sampling of some of Texas’ best (most of these pieces have appeared in the traveling Texas Crafts Exhibition organized by the University of Houston’s Blaffer Gallery), the only unifying characteristics are technical excellence and a free-wheeling eclecticism that often combines age-old techniques with the chic appeal of modern art. Paulina Van Bavel-Kearney’s ceramic vase, for example, has been colored and fired by methods known for centuries, but its lean shape has the same elegance as the radically simplified figurative sculptures of pioneer modernist Constantin Brancusi. Ann Matlock’s weavings can suggest recent color-field paintings. Other pieces, like the weavings of Margaret Sheppard, give a modern resonance to the repeated patterns of traditional folk art.

These objects are more than a means of combining art and life; they also impose a way of life on the people who make them, and it isn’t a particularly easy one: there are long, physically demanding hours in the workshop, a still uncertain market, and little of the fame freely given painters and sculptors. For most craftspeople, a modest living and the satisfaction of using their remarkable appendages for something more challenging than removing the foil from a TV dinner have to be reward enough. Consumers—who can patronize artisans at their own studios, galleries, and street fairs or through architects and interior designers—have the more reliable pleasure of possessing something beautiful that they can drink from, wear, or use to store the things they own. And as more craft objects enter important public and private collections, they will begin to be seen as investments with as much potential as prints, paintings, and sculptures. But while you are waiting for your favorite bedspread, cabinet, or goblet to appreciate in value, don’t neglect to use it. After all, that is what it was made for.

Ann Matlock

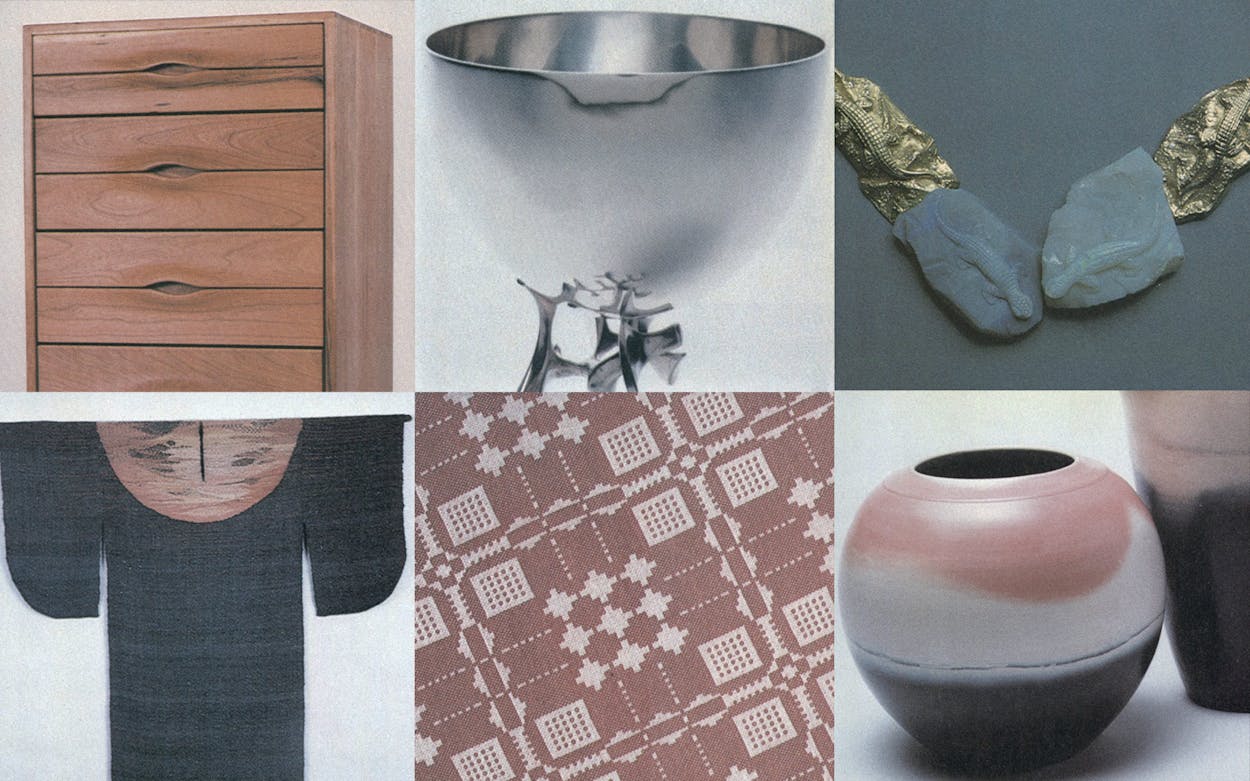

When this caftan is not being worn, it could easily hang on your living room wall instead of languishing in the closet. Ann Matlock, who lives in Austin, hand-spins all her yarns from natural fibers and dyes them herself with flowers, roots, and bark, so she starts with her own subtle palette of hues. Woven together, they mix to create a glowing diffusion of color that recalls passages from Impressionist landscapes.

Roger Deatherage

A solution to the problem of the boring bureau is this chest of drawers by Roger Deatherage of Houston. Superb craftsmanship, including immaculately dovetailed joints, makes the pieces of wood look as though they grew together instead of being assembled. This organic quality is enhanced by the drawer handles, which look like they are about to pucker up.

Brian Mikeska

The owner of this necklace once had a problem: what to do with two large opals (bought in San Francisco’s Chinatown) crawling with a pair of carved lizards. Brian Mikeska of Austin came up with a bold solution. He set off the stones with a couple of his own cast-gold lizards sunning themselves on crinkled sheets of gold studded with tiny diamonds. With the gold shining, the opals iridescing, and the diamonds sparkling, the necklace seems to have a mysterious internal power source.

John Rogers

A seemingly weightless silver chalice sprouts from the bramblelike stem of this goblet. John Rogers, who lives and works in Bandera, cast the freely sculpted stem with the lost-wax process; the cup was made from a single sheet of sterling hammered over a series of wood and metal forms. The contrast of shapes and textures gives visual excitement to a very useful object.

Margaret Sheppard

A weaver for thirty years, Houstonian Margaret Sheppard calls the pattern for her coverlet “snowballs and window sashes with a pine tree border.” Cheerful and vivid in domestic cotton and Swedish wool, it combines technical precision with all the charm of folk art.

Paulina Van Bavel-Kearney

Starting with a basic wheel-thrown vase, Paulina Van Bavel-Kearney of Austin has sculpted an undeniably human quality into this ceramic piece. The satin finish and earthy colors are produced by a combination of slips (a thin clay-and-water mixture), sawdust firing, burnishing with the palm of the hand, and the minerals in the clay itself.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Art

- TM Classics

- Crafting