This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The Shack, as it is called, has stood on Abrams, at the edge of downtown, since the streets of the neighborhood were paved with wood. It is a modest house, not nearly as impressive from the outside as many of its finer neighbors on this old East Dallas street, but on the inside it is a wealth of stained glass and hand-carved cabinetry. Over the years, the house has grown like the city itself, expanding this way and that until its original shape is as unrecognizable as the street it sits on, which is now a busy boulevard. The house has the warmth, solidarity, and charm that one expects in an older home, and, just as an overstuffed chair gradually takes on the shape of its owner, the Shack has come to personify the man who spent a lifetime building it, Roger McIntosh.

As a boy growing up in Dallas, Roger McIntosh became fascinated by the craftsmen working the fine, hand-painted, stained glass at the Dallas Art Glass Company. Then and there he decided on his career, and by his late teens he was employed at the Dallas branch of Pittsburgh Plate Glass. His skill was such that he came to be one of the foremost designers of fine glasswork in the country by the time of the Depression of the thirties. For the churches and wealthy families that could still afford it in those hard times, stained glass was a symbol of taste and social standing.

Tastes change, though, and gradually ornamental glass lost its appeal. Instead of being considered chic, it was thought of as old-fashioned. Orders fell off and, in the forties, Pittsburgh Plate Glass phased out its Art Glass Department and instituted a Modernize Main Street campaign. Ironically, Mr. McIntosh spent the rest of his career designing plate glass storefronts.

In 1922 he had bought a small house on Tremont (now Abrams). Nicknaming it the Shack, he began to work on it that same year, increasing the floor space and replacing ordinary windows with stained glass in almost every room. He also added much hand-carved cabinetry. One cannot help concluding that the house became the major outlet for his artistic energies.

Although most of the glasswork in the house is Mr. McIntosh’s, a small amount was done by his wife, Georgia, an artisan who also worked at Pittsburgh Plate Glass. After her death in the late forties, he continued his work unassisted and more and more came to rely on his friends for a sense of family. In particular, he grew close to Gene Richardson, a young man who went to work for him in 1947. For years, Richardson and his wife, Kathleen, kept an eye on Mr. McIntosh and the Shack, and when he became too old to care for himself, they took him to live with them.

Gene Richardson describes Mr. McIntosh as “a literate man with beautiful manners” who took great pains with everything. “When he was well into his eighties,” Richardson recalls, “I would often come by to check on him in the early morning and find him having breakfast alone. The table would be set with a linen place mat and napkin, an orange would be carefully sectioned with a cherry placed in the center, an omelet would be decorated with a sprig of parsley on top. Each meal was prepared as though at any minute someone were going to photograph it.” When Mr. McIntosh died early this year at the age of 88, he left the Shack to Gene and Kathleen. They, in turn, have made it their home, but are maintaining the house much as it was while he was living.

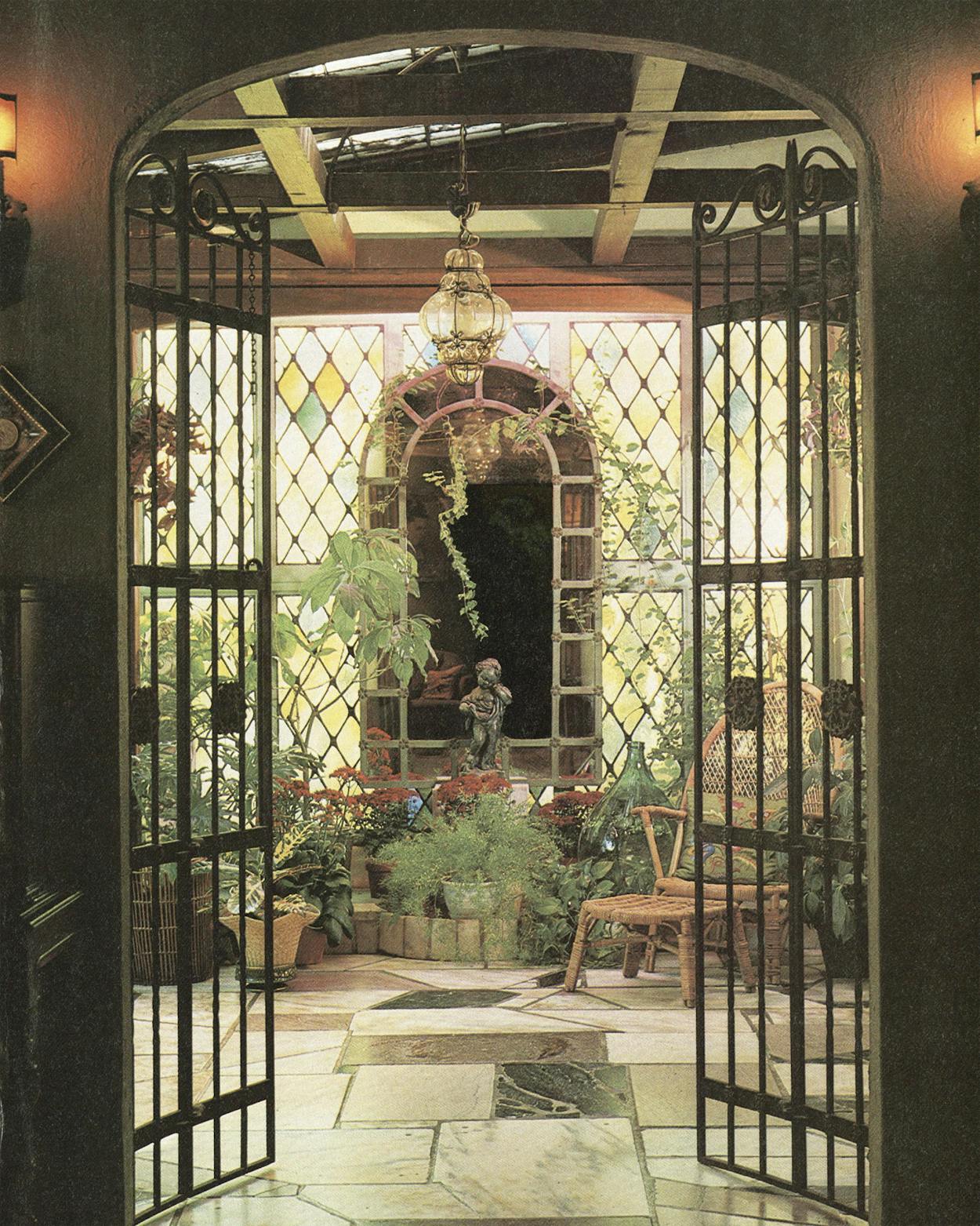

Roger McIntosh created the Shack as deliberately as he created his life. He made extraordinary use of his first love, glass, personally creating nearly every window, mirror, lamp, and light fixture in the place. Each window is a fine and imaginative example of the craft. There are stained-glass panels set into many walls—a glorious peacock in the entrance hall, a sprightly arrangement of dogwood blossoms in the kitchen. Tooled lead-and-glass sliding doors separate rooms. Italian-process acid-etched mirrors reflect one room into another. Thick glass bricks form exterior walls behind cabinets and closets, providing them with an unexpected burst of natural light.

There is more. Besides the glass, almost every piece of wood in the house—cabinets, bookcases, moldings, shelves, beams, doors, baseboards, and ceilings—was carved and fitted by Mr. McIntosh. There are many different textures and coverings on the walls, and woodwork is finished in an amazing variety of glazes, often in the same room. Mr. McIntosh was working on his last project, an indoor hibachi in a kitchen niche, when he was almost 85. A lifetime of handiwork is in the home.

Full of niches and nooks, the house has a definite place for even the most purely decorative objects. An intricate metal sculpture of a spider spinning a web has been whimsically placed in an empty arch, just where a real spider might be. A door with a leaded glass mirror and shelf opens to reveal a closet used only for storing light bulbs. The kitchen cabinets, as carefully fitted as a Pullman car, have a slot, a hook, or a shelf for anything a cook could use. On the back wall of one kitchen counter is a colorful stained-glass panel of a hen with her eggs; in front of the panel sits a wire basket filled with eggs. Elsewhere in the house are cabinets that are only for hats, drawers that are only for gloves, doors that open to become three-way mirrors, and a carved exterior wood awning over the one window where one is supposed to enjoy the view of downtown Dallas.

The extraordinary tidiness of the house is nowhere more evident than in the work studio. One end of the large room is a massive one-and-a-half story walk-in fireplace surrounded by comfortable chairs next to a bay of stained-glass windows. The opposite end of the studio, where Mr. McIntosh worked, is filled with drills, saws, and files hanging over a bank of cabinets.

Not only does everything have its place, but it is also clear that Mr. McIntosh never came across an item that he felt he could not use. Scavenged objects have become integral parts of the house. The hexagonal bricks that once lined old Ross Avenue now pave the patio floor; wooden crates used for shipping glass were transformed into carved ceilings in several rooms.

Mr. McIntosh’s plan for the Shack was to create something interesting in every room and to provide pleasant vistas between the rooms. He succeeded with a great deal of admittedly eccentric style. High under the eaves of the garage roof and visible from several rooms in the house is a charming stained-glass panel of a spider weaving its web. No doubt it served as a reminder to Mr. McIntosh that the most intriguing habitats are those that the dwellers create entirely from their own needs and desires.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Art

- TM Classics

- Architecture

- Dallas