This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

It’s the one thing dedicated antique shoppers dread most.

After all the stalking, the dead-end tips, and the fruitless touts, after they finally spot the one thing they can’t live without, there’s the sticker—NFS. Not For Sale, it announces, signifying that at least one other person can’t live without this particular item either.

What causes dealers, through whose hands have passed thousands of desirable objects, to fall in love with something and want to spend the rest of their lives with it, for richer or for poorer? And speaking of poorer, how can merchants in these days and times refuse to sell a piece of merchandise at any price? The answer lies in the reason many people become antique dealers: They have a consuming passion to surround themselves with beautiful objects. Indeed, the majority of dealers are first and foremost collectors; many of them go into business simply because the confines of space dictate getting rid of the old to make way for the new. As for any rational explanation of what makes one specific object The One, more than a few dealers have no answer simply because they never considered the question. If something pushes your buttons, you’ve just got to have it.

We asked some of Texas’ top antique dealers to show us the one thing that really has a hold on each of them. We hope you like the items—but not too much. Because you’ll never, ever own them.

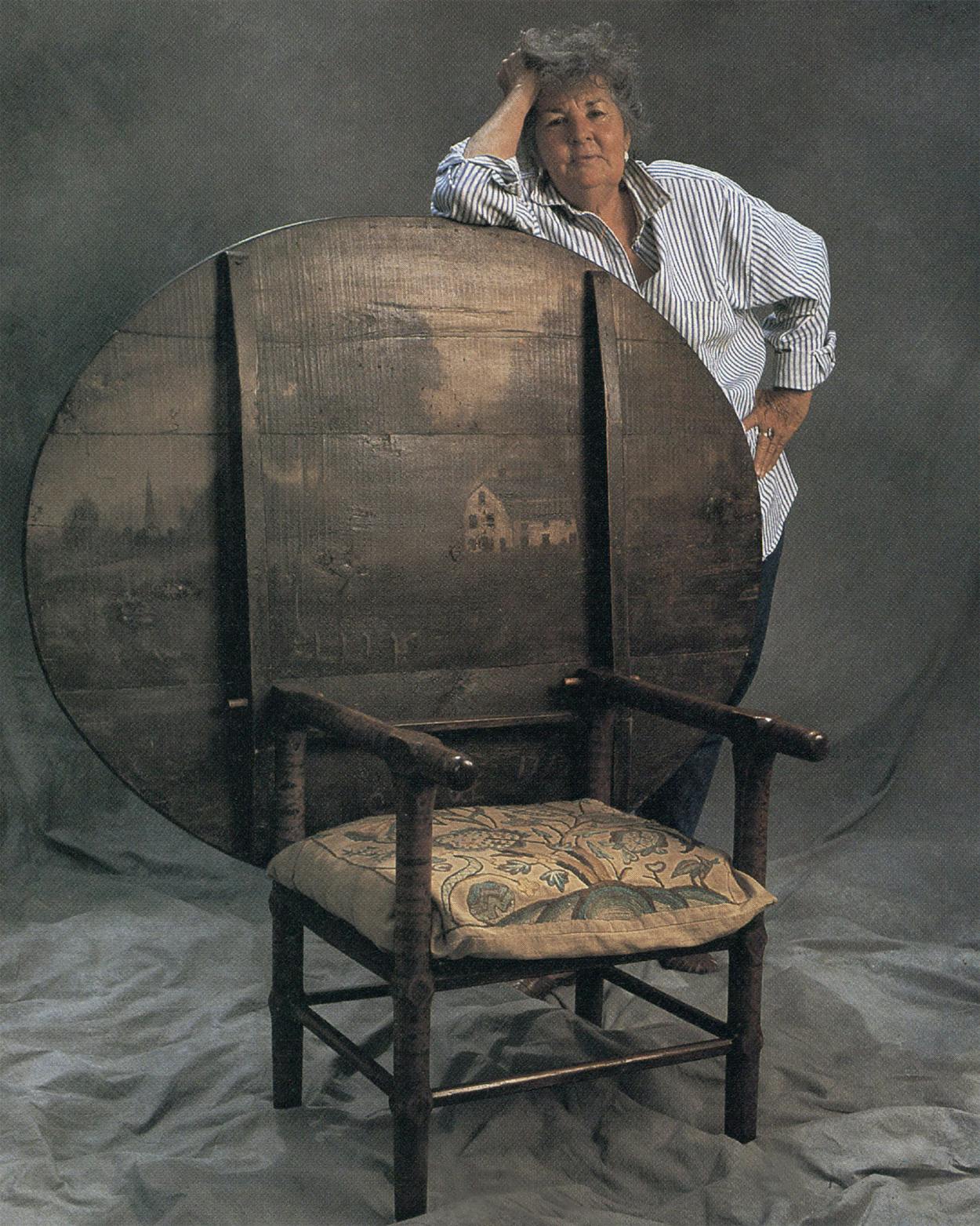

June Worrell

Houston

In 1966 June Worrell spent two steamy afternoons sifting through the attic of a soon-to-be-demolished house near downtown Houston. She paid a man $10 for parts to a toy train she had found. It turned out it wasn’t his house; it also turned out that the cute little train set—an elevated Ives train—was one of three extant in the country (F. A. O. Schwarz has another) and was worth well into five figures. Worrell learned that news after trading it to a prominent toy collector for this 1777 American painted folding chair table from a home in New England. The piece had spent the better part of its life on the porch of Burough Hall in South Carolina, owned by the Pulitzer family. Worrell, who has refused offers from the cream of American antique dealers, thinks she came out of the trade just fine.

Daphne Daniel

Austin

Daphne Daniel’s shop is a crash course in the Anglophilia raging through American design circles. She’ll gladly part with any of it—except this little tin box, which typifies, Daniel says, “the kind of care and effort lavished on the most common objects” in the nineteenth century. The box was made in 1887 to hold Keen’s mustard; its other functions were decorative and patriotic. It commemorated the reigns of the two monarchs—George II and Victoria—under whom Keen’s mustard was produced. It also celebrated, through chromolithographed scenes of India, Canada, Australia, and Africa, an empire upon which the sun never set.

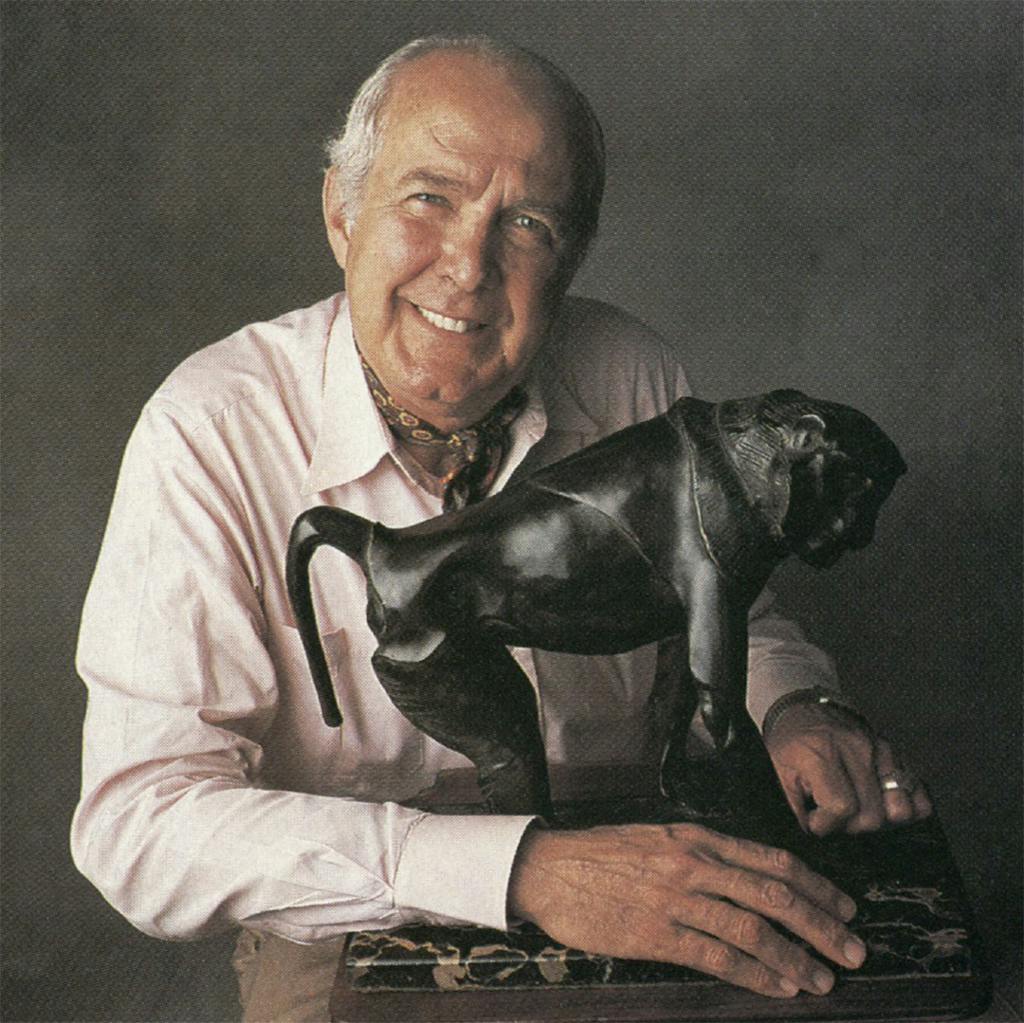

Paul Knight

Pittsburg

There are suggestions of Cubism and hints of Art Deco stylization in this bronze baboon by Italian artist Rembrandt Bugatti—odd influences, because the sculpture, cast in 1910, predates both. Paul Knight, who deals in antiques and quilts from his East Texas home, bought it five years ago in Florence, Italy, from a dealer with whom he trades regularly. “It’s not the kind of thing he ordinarily handles nor the kind of thing I ordinarily buy,” says Knight. “I just love it.” No other explanation is needed.

Susan and Sean Acrey

Roanoke

Nowadays a lot of people collect the brightly colored and fancifully formed ceramic pieces known as majolica, but Sean and Susan Acrey really collect majolica. Their mania started when they received a shipment of 12,000 pieces—none of which they particularly cared about—to sell at their shop. Soon they were taking home a dish here, a pitcher there; now the collection must be subdivided: bread platters, minton pieces, and fish-related items (including a dozen sardine boxes). The crown jewel is this English umbrella stand made by Minton manufacturers in 1873, probably produced only for exhibition and not for sale, just as it is now.

Jerry Jeanmard is a Houston designer.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- TM Classics