When Kirk Kirkland was a teenager in East Texas in the 1980s, alligator gar were trash fish. Anglers used the dismissive term to refer to species that ate the fish they were interested in catching. But in the mid-1990s, Kirkland, who was by then working with his dad selling fish, started getting calls from Dutch anglers who wanted to come to Texas in search of alligator gar. To the Dutch, the ferocious-looking gar with their gnarly teeth were an exotic trophy fish. One of the biggest fish in North America, the species can reach more than two hundred pounds and eight feet in length. It was bigger than anything the Dutch could catch at home.

Kirkland and his dad sold mostly catfish, but they caught alligator gar too and were happy to provide guiding services for extra income. Over the years, they welcomed a steady trickle of visitors. Then television producers began calling, looking for big fish to build TV shows around. That’s when the guiding business really took off. “Americans didn’t know you could fish for alligator gar on rod and reel,” says Kirkland. “Once they saw that on TV, they wanted to do it too.”

Since then, Kirkland has become the gar guru of East Texas. He holds more than a hundred fishing records from the International Game Fish Association (IGFA), and his business, which operates a small fleet of boats and employs several guides, is thriving. The Trinity River has become the go-to destination for alligator gar sportfishing, which is now strictly regulated and mostly done as catch-and-release. As a result, the gar population in the river—which is the longest that is entirely contained by Texas—is healthier and more robust than it’s ever been.

It’s a rare good-news story for a freshwater megafish, says Zeb Hogan, a biology professor at the University of Nevada, Reno, and the host of National Geographic’s Monster Fish. (He was one of the first people to film a TV show about the alligator gar with Kirkland.) Two decades ago, Hogan launched what he called the Megafishes Project, a conservation quest to find, study, and protect the world’s largest freshwater fishes, species that live exclusively in rivers and lakes and can grow to at least six feet long or more than two hundred pounds. As it turns out, there are about thirty such fish in the world, including the alligator gar, and they are among the most endangered animals on the planet.

I first met Hogan in 2006, when I went to see him in Cambodia on a National Geographic assignment. I’ve since shadowed him on his world travels in search of sumo-sized stingrays and colossal catfish, and we’ve written a recently published book together called Chasing Giants: In Search of the World’s Largest Freshwater Fish. It tells the troubling story of the world’s megafish, most of which are highly endangered because of a variety of threats, such as overfishing, dam building, pollution, and climate change. One huge species, the Chinese paddlefish, which could grow more than twenty feet long, actually went extinct in the early 2000s. The idea of an enormous animal like that disappearing from this world is disturbing, especially since many megafish, including gars, have been on Earth for more than 100 million years.

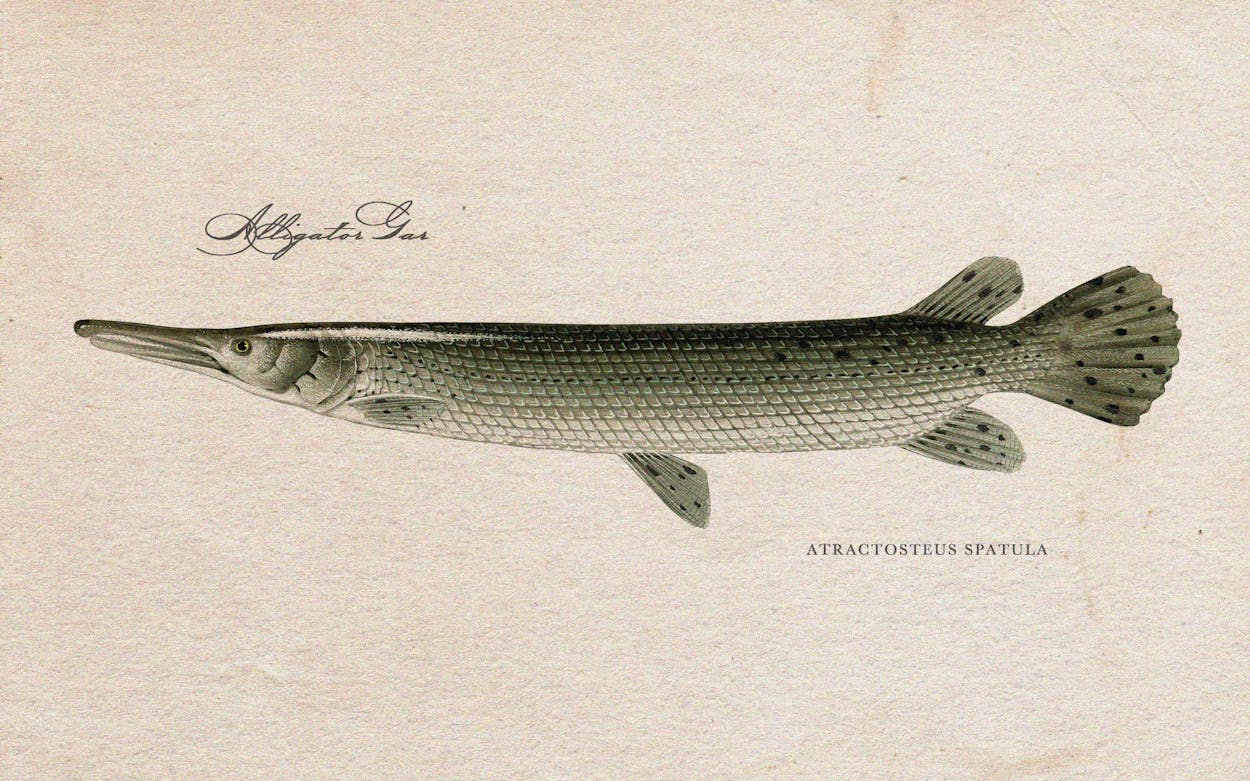

In fact, the fossil record of Lepisosteidae, the family of thick-skulled and heavy-scaled fish to which gars belong, goes back 157 million years, with cranial remains discovered from that time in present-day Mexico. Of the seven species of gars that exist today—four of which are found in Texas—the alligator gar was the first one to emerge, about five million years ago, and it’s bigger than all of the gars of the very ancient past. It can be distinguished by the two rows of teeth in its upper jaw, as well as its wide head, which is a bit similar in shape to an alligator’s when viewed from above. (Many a fisherman has confused a shortnose or a longnose gar for an alligator gar, leading the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department to call the latter “one of the most misidentified species of fish around.”)

Because gars haven’t changed much in appearance and physiology from their ancient ancestors, they are sometimes referred to as “primitive.” This implies that gars are not as evolved as other, more recently developed creatures, but this is simply wrong. In fact, every organism is the most evolved of its kind. Hidden within their prehistoric bodies is a string of adaptations that have served these river giants well for millions of years. In the evolutionary game that has wiped out more than 99 percent of all vertebrate species through time, the alligator gar is evolved for survival.

Gars are opportunistic feeders that primarily prey on fish but also eat crabs, turtles, birds, and small mammals, and their spiral guts can wring the maximum nutrients out of kills. The alligator gar’s eggs are toxic, serving as a defense mechanism against potential predators. (The eggs are also poisonous to humans if ingested, one reason gars are not popular food fish.) Like the South American arapaima, another giant freshwater fish, the alligator gar can breathe air from the surface. In fact, the fish may obtain as much as 70 percent of the oxygen it needs from the atmosphere, with its spongy and highly vascular air bladder behaving like a lung to aerate the fish’s blood. This lets the alligator gar live in places where most fish cannot survive, such as warm, sluggish waters low in oxygen.

According to FishBase, an online database, the alligator gar can grow over three hundred pounds, making it the largest true freshwater fish species in North America. I say “true” because there are other giant fish swimming in American rivers that grow larger, such as the white sturgeon, but that species also moves into the sea, so it cannot be considered a strictly freshwater fish. At the same time, alligator gars can tolerate a fair amount of salt in the water, up to seven or eight grams per liter, and they have been spotted around Louisiana’s barrier islands.

The alligator gar’s natural range once included the entire Mississippi River basin, as far north as Iowa, but it’s now known to live only in the southern belt of the United States, from Texas and parts of Mexico in the west to Florida in the east, with an isolated population in Cuba. Not surprisingly, humans have everything to do with that decline.

Alligator gars have long been venerated among several Native American tribes, including the Houma and the Coushatta, with the fish even depicted in the latter’s tribal seal. There is a long tradition of Native Americans using gar scales to make jewelry and tools, leather products, and skin oil for insect repellent. But the alligator gar’s reputation among anglers has historically been far less stellar. Resource managers in the past recommended culling them, and fishermen shot them with bows, clubbed them with paddles, and threw their carcasses up on the banks to rot. In the 1930s, officials used “electric gar destroyers” to systematically exterminate the fish, and in several states it was long illegal to return gars to the water alive once they’d been caught.

Those removal efforts, combined with habitat loss, pushed the alligator gar deeper into the swampy rivers and brackish bayous of the South. At the end of the twentieth century, only Texas and Louisiana had stable populations, and even there the gar had no legal protections, with people free to catch as many as they liked. Any attention paid to it was negative and attributable to misconceptions surrounding the species and its impact on sport fishes. Historic removal efforts, chronic overfishing, and habitat loss due to river fragmentation and flow modifications resulted in the extirpation of gar populations from many drainages.

But something strange happened. The image of the alligator gar began to change. It started with a treatise written by a University of Idaho fisheries biologist named Dennis Scarnecchia, published in the journal Fisheries in 1992. The view of alligator gars as harmful to game fishes and recreational angling was wrong, Scarnecchia wrote; in fact, giant fish were important contributors to ecosystem stability and function, balancing predators and prey, and therefore instrumental to more successful angling in the long term.

Until the late 1990s, no one had really studied the alligator gar. As a result, basic knowledge about its life history and ecology lagged far behind that of most fish. The little work that had been done had focused largely on the fish’s diet; the long-held belief was that gars ate the game fish humans wanted to catch. As it turns out, they don’t. Researchers like Allyse Ferrara and her colleague Solomon David at Louisiana’s Nicholls State University found that gars eat more or less whatever prey species are abundant, and are more likely to go after shad and minnows—and even things like small mammals, waterfowl, insects, and crustaceans—than game fish, such as sunfish and bass.

Scientists were able to develop a greater understanding of the important role that alligator gars, as top predators, play in maintaining healthy ecosystems. That knowledge of the biology and ecology of the species has been crucial to advance science-based management of alligator gars.

Which brings us back to the Trinity River. In 2009, the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department instituted a statewide one-fish-per-day regulation for the alligator gar, intended to maintain the current status of the Texas population until the department had amassed enough information to effectively manage stocks based on scientific data. Since then, researchers have found that Texas gar populations are relatively healthy, both in abundance and size of fish. They’ve learned that females grow significantly larger and older, with a lifespan of more than sixty years. Years with particularly high recruitment (the process by which very young, small fish survive to become older, larger fish) occur relatively infrequently, and rely on the timing, magnitude, and duration of flood events. “All of this information has been critical in developing science-based recommendations for the management and conservation of Texas alligator gar fisheries,” says Dan Dougherty, a research biologist with Texas Parks & Wildlife’s Heart of the Hills Fisheries Science Center.

As for Kirkland, he recently guided a client who ended up landing another IGFA record after catching a 251-pound alligator gar, the largest gar ever caught on an 80-pound line. The all-tackle world record for the alligator gar still stands at 327 pounds. But Kirkland expects to break that in the not-too-distant future. “We’ll do it,” he says. “There are plenty of monsters in the river now.”

- More About:

- Critters