About that leopard that went missing at the Dallas Zoo last week: I had nothing to do with it. But when you write a book about a leopard escaping from a zoo, and then a leopard escapes from a zoo, you tend to fall into the person-of-interest category.

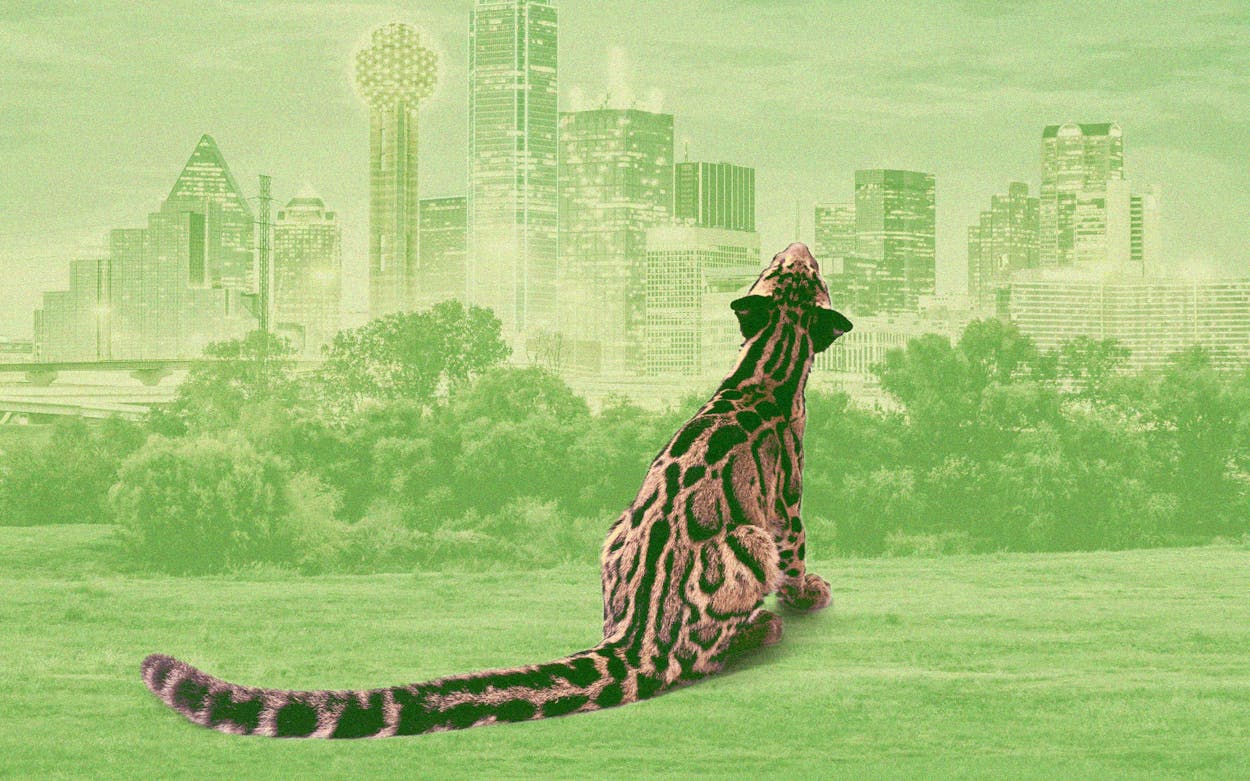

“The Zoo is closed today due to a serious situation,” the Dallas Zoo tweeted at 10:20 a.m. on Friday, after a four-year-old female leopard named Nova was reported missing. She was found later that afternoon, hanging out near her habitat, to which she was returned—but not before her escape became national news and launched a multitude of wisecracks on social media.

Zoo officials and police believe the escape wasn’t Nova’s idea—that someone, for reasons unknown, cut through the mesh of her enclosure to let her out. (Zookeepers found a similar a hole in a monkey habitat, though none of the monkeys took advantage of it.) All the razzing emails, texts, Facebook posts, and tweets that came my way on Friday suggested that I had a transparent motive: to sell books.

The book under suspicion is my novel The Leopard Is Loose, which was published last January and is based on a real-life incident that happened in Oklahoma City in 1950. Although I had a strong sense of déjà écrit when I heard about the Dallas escape, as the case of the missing leopard unfolded, I was struck more by the profound differences in the reactions between 1950 and now.

To be sure, we’re talking about two very different creatures. Nova is a clouded leopard, a smallish, 25-pound predator no larger than a bobcat. The animal that escaped from the Oklahoma City Zoo in February of 1950 was an Indian leopard that weighed 175 pounds and was a member of a species that has a documented history of killing humans. His name was Luther, but he quickly became known as “Leapy,” because he managed to spring from a deep pit in full view of six astonished kids.

I was born in Oklahoma City and was less than two years old at the time, but I grew up hearing about the leopard escape and how it had paralyzed the city for three days. The mood of menace, hysteria, and hyperbole was immediate. “It sounds as if many persons are in great danger,” a famous adventurer and wildlife photographer named Osa Johnson warned the readers of the Daily Oklahoman. “I dread to think of people—children and old people—threatened by such an animal. . . . If they need me, I’ll fly to Oklahoma with my 9.3 Mauser and I’ll help them. I’ll help them blow his brains out. It must be done quickly.”

But the citizens of Oklahoma City were already on the case. The Civil Air Patrol and the Marines were mobilized, along with about three thousand self-deputized leopard hunters, who scoured the outskirts and inskirts of the city with shotguns, rifles, and hunting dogs. As surveillance helicopters and civilian aircraft patrolled from the air, children were kept inside. According to Life magazine, hundreds of acres of brush were burned down, the Red Cross designated Oklahoma City a disaster area, and signs sprung up in sporting goods stores advertising leopard-hunting equipment. The entrepreneurship wasn’t all about bloodletting. A department store sold $1 “Killer” leopard T-shirts, and an a cappella singing group called the Leopardaires leapt into being. An enterprising striptease artist even incorporated layers of leopard-print garments into her routine.

In the end, none of those hunters bagged the leopard. Like Nova, Leapy probably never wandered far from his enclosure. After three days, he came home and ate the drugged horsemeat that had been set out to sedate him so he could be recaptured. But the amount of chloral hydrate in the meat was too much. The overdosed leopard went into a coma and died fifteen hours later.

There was no citywide outpouring of grief, just relief on the parts of parents with young children and an overall deflated realization that the fun was over. “In storage closets all over town,” mock-lamented the newspaper’s humorist, “go some of the fanciest buckskin fringed hunting jackets, those dashing woodsy caps. . . . Shooting irons dating back to the civil war were stacked with a final sad caress to gather dust for another decade.”

The leopard’s demise was an ignoble anticlimax. But Oklahoma City couldn’t quite let Leapy go. He was stuffed and put on exhibit in the zoo. His carcass remained there for many decades; I saw it as a very young boy. In its taxidermied afterlife, the leopard was nothing like the phantom killer of my imagination. It looked small and confused, and as I stared at it I felt pity for the first time I can remember.

Who knows how much more insane the Oklahoma City leopard escape would have been if it had occurred in our own amplifying, reverberating social media age, with the sky full of camera drones from Best Buy and the hunters ferociously competing not to kill the beast but to document it on TikTok? But the past belongs to the past. And with that long-ago leopard hunt lodged in my memory, I see more clearly the widening attitudes—particularly about animals—between the middle of one American century and the first decades of another.

In the 1950s, an animal in a zoo was like a painting in a museum: something you looked at, assessed with whatever degree of interest or fascination it warranted, and then moved on from to the next exhibit. It was a living being but not necessarily a sentient one. When it came to the short-lived adventures of Leapy the leopard, there was an undercurrent of bemusement among the citizens of Oklahoma City but not much empathy. The main emotions on display were excitement and terror. An escaped leopard was a nightmare creature—“All Leopards are Cruel and Cunning” screamed one headline in the Daily Oklahoman during the three-day chase—and the person who killed it would be expunging that terror at the same moment as grabbing a sought-after trophy. The experts who weighed in on what the leopard might be thinking were not animal behaviorists or zoologists but big-game hunters, and the end of the story was a giant civic letdown not because the animal ended up dead, but because no one got to shoot it.

By contrast, the concern about Nova centered clearly on her welfare: “She was just a curious bby,” “Please don’t kill this poor baby,” and “It’s always the animal that pays the price, with their life, for human mistakes or idiocracy!!!!!!”

As to who let the leopard out, at this point no culprit has been identified, nor have I found it necessary to turn myself in. But the striking thing is that in this case, unlike her predecessor in Oklahoma City 73 years ago, the leopard herself was not the culprit—not a willful escapee looking to feast on human flesh but a disoriented little cat who was eager to come home. “Oh-so-many guests,” the Dallas Zoo tweeted after she was recovered, “stopped by to wish her well.”