Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick published an opinion column in the Houston Chronicle on Wednesday explaining his side of a story that’s been attracting national attention. Joy Alonzo, an assistant professor of pharmacy practice at Texas A&M, was speaking on the opioid crisis as a guest lecturer at the University of Texas Medical Branch back in March when she allegedly made a negative remark about the lieutenant governor. In the audience that day was a student who was the daughter of Texas land commissioner Dawn Buckingham, a Republican ally of Patrick. Buckingham’s daughter told her about the remark. Buckingham then relayed it to the notoriously thin-skinned lieutenant governor. He reached out to Texas A&M chancellor John Sharp to request that he “look into” Alonzo’s lecture. The professor was “placed on administrative leave pending investigation re firing her,” as Sharp put it in a text message to Patrick that was obtained by the Texas Tribune.

In his article for the Chronicle, Patrick waved away critics who accused him of attempting to suppress free speech and offered a defense of his decision to contact the chancellor. He has no issue with legitimate policy critique, he claimed, as “that is part of being an elected official.” Rather, he said, “If what I heard was correct, it was a false and inappropriate personal attack on me.” Patrick, curiously, did not report in his article what was allegedly said. But on Wednesday, Buckingham tweeted that Alonzo told the class “Your lieutenant governor says those kids deserve to die” when discussing teens who died of fentanyl overdoses in Hays County. Representatives for Texas A&M did not make Alonzo available for an interview and did not respond to a question about the specific remark that spurred the investigation, but Alonzo issued a statement to the Texas Tribune, provided by the university, that her comments had been “mischaracterized and misconstrued.” The school’s internal investigation of her remarks could not confirm she’d violated any rules, and Alonzo has kept her job.

We still don’t know from a firsthand source what was said. If it was exactly as Buckingham described it, though, Alonzo’s comments are not a strictly true description of Patrick’s words on the subject of fentanyl overdoses. But as the leader of the Texas Senate, Patrick has consistently stood in the way of policies experts say would mitigate those deaths. This session the House passed a bipartisan bill, endorsed by Governor Greg Abbott, that would have legalized the sale or possession of fentanyl test strips, which are currently classified as drug paraphernalia even though the National Institutes of Health and the Food and Drug Administration say they save lives. Patrick let the House measure die without a hearing in the Senate. The argument typically levied against legalizing these strips is that the individuals who would use them to ensure the drugs they’re taking aren’t laced with something lethal shouldn’t be using drugs at all.

Even if Buckingham’s secondhand account of what was said is entirely accurate, the characterization of Patrick’s stance is protected speech, according to Alex Morey, a lawyer at the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, a First Amendment advocacy nonprofit. “The courts have said that sometimes you speak in ways that are vituperative and inexact when emotions are high, and that’s okay, because in our country, you’re allowed to criticize public officials,” she said. “That’s what separates us from the Chinas and the Russias and North Koreas and Turkeys of the world.”

It’s never fun to learn that someone is telling falsehoods about you. I speak from experience, as Patrick spread misinformation about me last year when he published a press release that included a wildly inaccurate timeline of requests I made for an interview with the lieutenant governor while I was reporting a story about his investments. But part of operating in public is accepting that the public is going to have things to say about you and your work, and that those things might not always be agreeable.

After addressing what offended him about Alonzo’s comments, the lieutenant governor then explained why he felt something that was said about him in a university setting should be “look[ed] into.” Does Patrick not have more important things to care about? Turns out, no; in his telling, part of his job is to call the chancellor of a Texas university to demand an investigation anytime he is made aware that a professor may have said something hurtful about any individual. “I would do this on behalf of any student or parent who called our office with a similar complaint,” he insisted.

All of the concerns expressed about academic freedom that have followed his call to Sharp, Patrick suggested, represent nothing more than pearl clutching initiated by the faculty senate. “Their outrage seems based on the belief that anyone who dares ask a question about what is being taught or said in a classroom at a state university is somehow challenging their ‘academic freedom,’ ” Patrick wrote.

That might be a compelling argument if the faculty senate were up in arms over, say, a student or parent who had the temerity to complain about something a professor had said in class. But the instructors’ concern is not that the comments of a colleague were challenged at all, but by whom they were challenged: a man who wields power and influence over the way the university operates—and its funding. “An administrator getting this message, knowing just what kind of government hammer that Patrick can bring down upon the university, can definitely constitute pressure from a government actor,” Morey told me.

Patrick has a long history of trying to limit speech he finds objectionable. During this year’s regular legislative session, he directed the Senate to take up a bill that would have ended tenure for professors in state colleges and universities, which he has said protects the employment of “looney Marxist” radicals. The measure ultimately died in the House, but it has already had adverse effects on hiring top academic talent, as the best professors are free to pursue opportunities in states where the protections guaranteed by tenure are unthreatened by lawmakers. Patrick also led a successful effort in the Legislature this spring to dismantle diversity, equity, and inclusion offices at public universities. In the past he has argued in favor of firing university professors who teach critical race theory—an academic framework that uses race as a lens to understand various legal, political, and social issues—to adult students at higher education institutions. He’s also stifled discussion of ideas he considers offensive outside of university settings; in 2021 he pressured the Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum to cancel an event featuring the authors of the book Forget the Alamo, which challenges the established narrative of the Texas Revolution.

In his editorial, Patrick framed the entire episode as one of “accountability” for college employees. But he gave little thought to what accountability means for someone in his position—which requires tolerance of criticism, however harsh or hurtful. To buttress his argument, Patrick invoked an analogy: accountability for college sports coaches. “A losing record will draw questions and criticism, often leading to their termination,” Patrick argues, suggesting that, while “sports and academics are different,” academia would benefit from a similar approach.

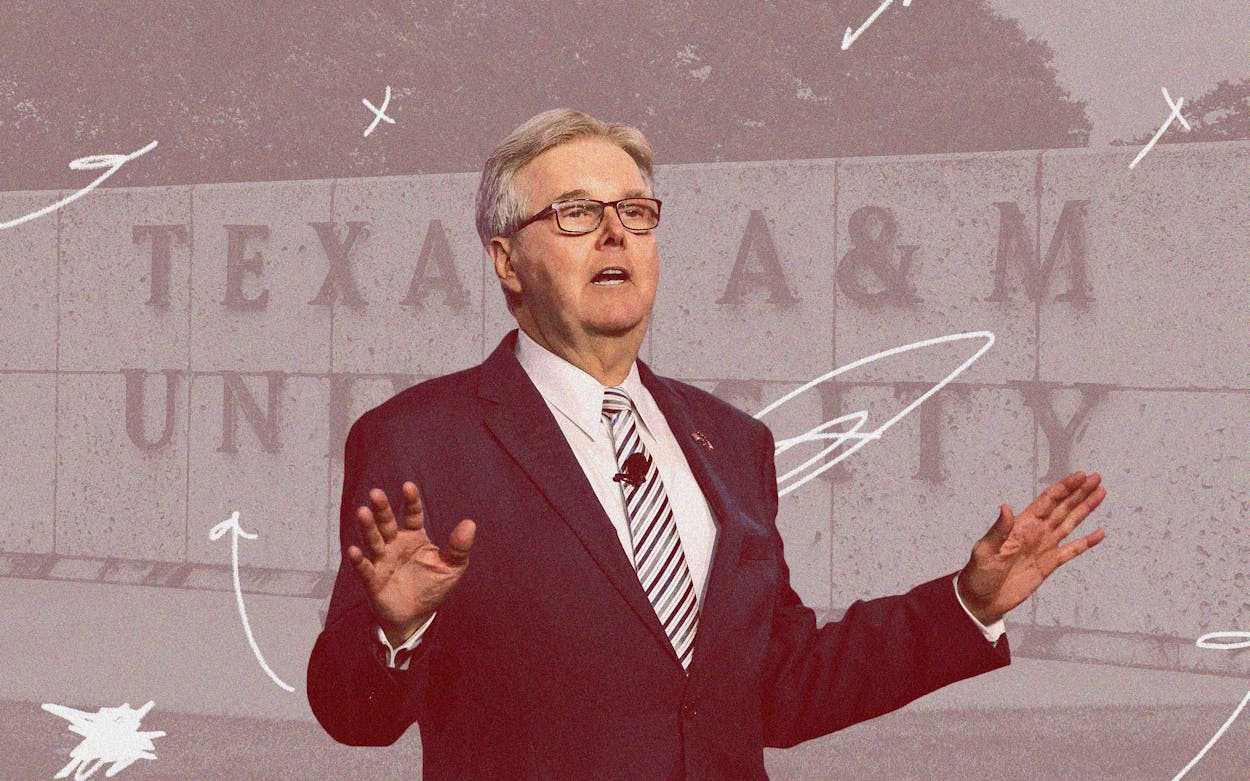

In a way, Patrick’s analogy is unintentionally quite fitting. As the Alonzo scandal unfolds, the Aggies are preparing for their sixth season under head coach Jimbo Fisher, following a 5–7 performance in 2022. Fisher earns $9 million a year, making him one of the highest-paid coaches in any sport. That’s roughly a hundred times what a full-time assistant professor at the university (Alonzo teaches there part-time), takes home in a year, and the price of a potential Fisher buyout—the largest in the history of the sport, at $86 million—makes him virtually unfireable, despite his failure to accomplish what A&M paid him to do when he got the job.

Some, in other words, can face accountability if they make the mistake of saying something that offends a powerful individual in front of the wrong person’s daughter, while others—those who happen to possess greater power and wealth—are to be insulated from consequences, whether those be termination from a coaching job or having to shrug off the occasional cheap shot from someone lecturing in a classroom somewhere. Assistant university professors are expendable, but their bosses’ relationships with folks as powerful as Patrick are not.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Dan Patrick

- College Station