This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

My addiction to courthouse culture was immediate and shameless. I first went to the courthouse in Dallas County as a young reporter for the Dallas Times Herald, and I was instantly mesmerized by the endless array of gritty dramas taking place there nine hours a day, 240 days a year. It seemed a magnetic, irresistibly fascinating place to observe the human condition, to witness human frailty and tragedy up close, and to see just how well or poorly everyone was coping with the business of living. The raw sensuality that the courthouse exuded made it constantly, almost perversely exciting. Today, twelve years later, I am still a courthouse junkie.

Part of what makes the courthouse so fascinating is its immensity. It is contained primarily in the huge, twelve-story county government center in downtown Dallas, but some functions spill over into the courthouse records building, the old nineteenth-century courthouse, and the recently completed county jail. This labyrinth is a far cry from its frontier progenitor, which consisted of only the bare essentials: a judge, a sheriff, a tax collector, a jail. Today the Dallas County courthouse includes a human services department, a mental illness department, a mosquito control department, and ten kinds of courts. There’s even something called a facilities department. The courthouse spends nearly $2 million each year on groceries, $400,000 on postage, $2 million on utilities. Elections are administered by the courthouse, as are public hospitals. The courthouse has become a city unto itself, whose residents fill their days by processing our most unpleasant public business.

The work of the judges, lawyers, bailiffs, and clerks employed here is rarely exciting or fulfilling or even interesting. Instead it is repetitious, banal, endless, necessary. Though the legal cases involving million-dollar swindles and gruesome murders are invariably the ones that make the headlines, the real stuff of any courthouse is the petty transgressions. Each day the county’s 24 criminal courts process roughly 220 minor misdeeds; cases are set, tried, dismissed, pleaded off. The prevailing ethic dictates that they be disposed of. Thus one is less likely to see high drama unfolding than clumps of attorneys shooting the breeze as they stand around a judgeless bench. Even when the matters under discussion will have immense consequences for someone, somewhere, courthouse people approach them with an odd, almost apathetic languor.

To the interested observer, however, this lethargy is just another characteristic of courthouse life. Sitting in any of the courthouse’s wide corridors, you can witness innumerable quiet dramas. A young man accompanied by his parents sits slumped and humbled on a bench outside the courtroom, waiting for his lawyer to return with the prosecutor’s first offer. Soon enough, the lawyer bustles out. Hushed words are exchanged and anguished gestures made—the offer involves jail time. This scene is repeated two, three, six times, until the defendant and his parents slump into resignation.

Linking the many aspects of the courthouse is an important cultural medium: the elevators. They carry the actors up and down, from set to set as the daily drama goes on. To step into a courthouse elevator is to become immersed in the culture. They are always full and, unlike bank elevators, always buzzing with conversation.

“Frank! Put any crooks away today?”

“Nah. Lost one this morning. One juror told me afterward she got distracted because my shoes didn’t match my suit.”

“Excuse me, but where is court number eight?”

“Fourth. You’ll know it. It’s the one where the judge isn’t there.”

“Give you two to one on the Williams case, not guilty.”

“Okay, you want to wrap that into a parlay with the bet on SMU we made this morning?”

All of the angst, the grief, the relief, the delicious black humor of the place, is at work in each of the courthouse’s six main elevators every moment they are in operation. And walking off the elevator into the crowded third-floor hallway, listening to the laughter and the chitchat, you discover the most endearing thing about the courthouse. Though nobody’s here for a good reason, everybody’s trying to make the best of things.

Randy Kucera’s First Case

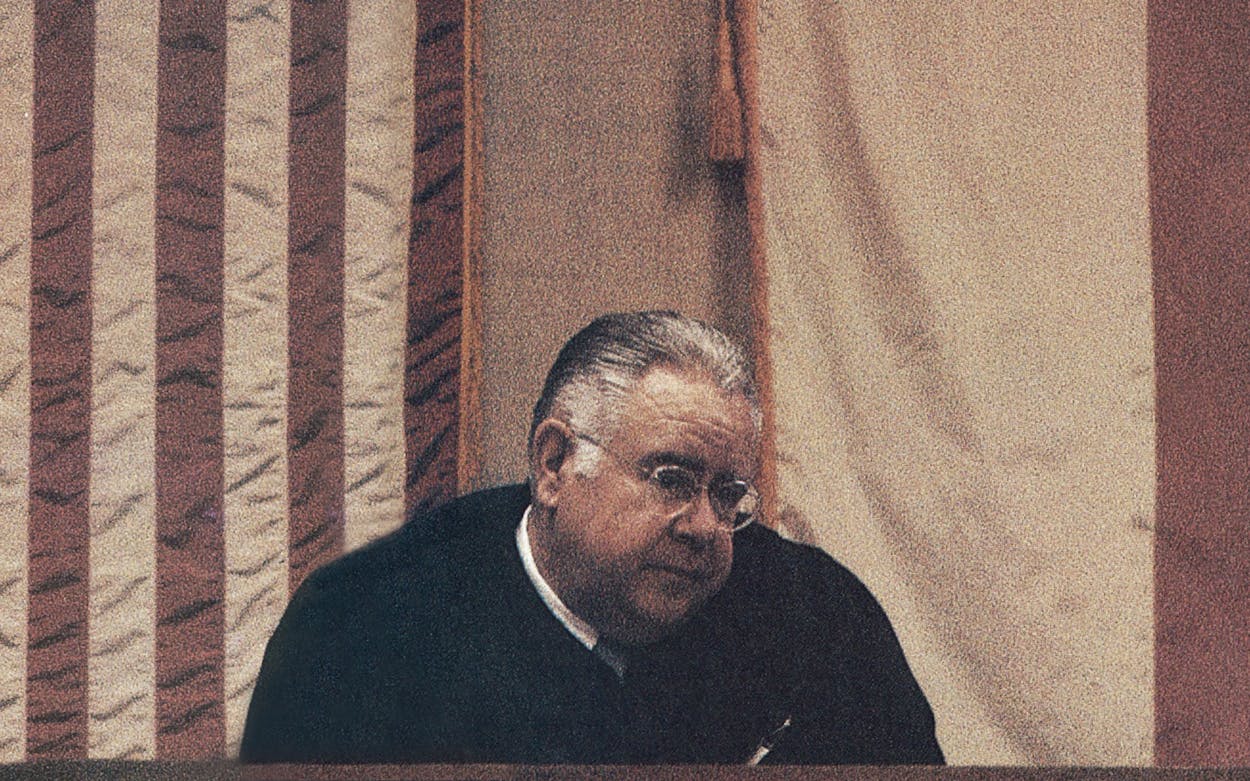

It’s Wednesday morning in Judge John McCall’s courtroom on the third floor of the Dallas County courthouse. Lawyers strut to and fro, carrying enigmatic sheaves of folders; a few inmates and their families and friends are draped on the seats at the back of the room. At the front, Judge McCall listens to a guilty plea with all the interest of an airline passenger waiting for his seating assignment. Like any courtroom in any courthouse on any day of the week, Dallas County Criminal Court No. 7 this morning is less a study in tension and urgency than in lethargic chaos.

The only person showing anxiety is Randy Kucera, a light-haired Yale graduate in his mid-twenties who is about to try his first case as a Dallas County prosecutor. Since joining the office of district attorney Henry Wade in October, he has been pushing paper in the traffic courts: a ticket for speeding here, one for running a red light there. This case—a misdemeanor DWI—is his first real action as a prosecutor. He knows the law, he knows the facts of the case, and he is relatively certain that his voice will not crack when he begins his opening statement to the jury. But there is a shadow of concern on his cherubic face. “I guess if there’s any anxiety,” he says dryly, “it’s that I have to go in there and convince the jury that I know what I’m doing.”

In truth, Kucera has even more cause for concern. Prosecuting crooks is an intensely competitive business, and young prosecutors are rated by the number of cases they win. Even when a case is settled out of court, which is what happens most of the time, the prosecutor must extract the maximum punishment possible. As for trials, he is expected to win. Prosecutors whose misdemeanor cases too often end in acquittals or probated sentences find it hard to move up to a felony court position.

Like all the prosecutors in Wade’s office, Kucera will try his case according to procedures outlined in the four-volume prosecutors’ manual. This encyclopedic collection of dos and don’ts covers every move that Kucera might need to make—from choosing jurors on the basis of religious preference to deciding what questions to ask and in what order to ask them. In a well-oiled DA’s office like Henry Wade’s, the odds are in Kucera’s favor as long as he painstakingly follows the book.

The DWI case at hand will rest on the testimony of Kucera’s witnesses, and he has rehearsed them carefully. The case involves a collision between the complainant’s auto and the defendant’s, but because the defendant refused to take a Breathalyzer test, there is no scientific proof that he was intoxicated. Kucera is certain that the defense will try to muddle the issue by asserting that the accident was not the defendant’s fault—a point that has no bearing on whether he was driving while intoxicated but that might sway the jury in his favor.

The complainant, a dour young woman named Dorothy Smith, appears worn down by the endless delays and inscrutable workings of the courthouse. Her version of the collision is straightforward. She was driving down Frio Drive in South Oak Cliff on the evening of February 12, 1983, about six o’clock. She stopped at the intersection of Overton Road, and because of the nature of the intersection, she had to edge her car slightly past the stop sign to see the oncoming traffic. Suddenly a car moving at high speed down Overton veered into her own, spinning it 180 degrees and pushing it over the curb at Frio and Overton. Her car’s right front fender was obliterated. The other car continued a hundred yards or so down Overton, then pulled over and stopped. The driver, a middle-aged man named Alvin Turner, walked back to her car and began berating her with obscenities. Smith says that he was weaving and swaying and his speech was slurred. She smelled liquor on his breath.

Kucera will buttress Smith’s testimony with that of a police officer who quickly arrived at the scene. Two other witnesses will also testify to Turner’s apparently drunken behavior. Even without a Breathalyzer test, the case against Turner seems tight. But there are problems that even an inexperienced prosecutor like Kucera can see. With so many witnesses, versions are bound to vary. Kucera is certain that the defendant was intoxicated, but it might just as easily be argued that the collision accounted for his agitated behavior. And Turner is a respectable-looking fellow with no prior record; he doubtless will be a good witness.

Kucera’s assistant, who is more experienced than he is, rushes into the room with a large manila folder. She has been in the courtroom selecting a jury. She nonchalantly opens the folder and reports, “Okay, they’ve struck six, nine, and thirteen. We’ve struck two, eleven, and twelve. Four women, two men.” Kucera nods nervously. He checks his watch. It is 11:40; jury selection took longer than he expected. He goes to tell Dorothy Smith that, like it or not, the Dallas County courthouse is running right on schedule.

Bob and Jeannie in Heartbreak Hallway

Bob* loved Jeannie.* Jeannie loved Bob. But things didn’t work out, so they got a divorce. Bob was supposed to pay Jeannie child support for their little daughter. Bob got behind, and now he owes Jeannie $3500. Jeannie has taken Bob back to family court, and Bob doesn’t seem happy about it at all.

The varied crannies of the courthouse buildings go by many names, but few are as fitting as “Heartbreak Hallway,” the name given to the floors of the old courthouse that house the county’s seven divorce courts. In stark contrast to the bustling, Turkish-flea-market atmosphere of the corridors outside the criminal courts, these hallways are eerily quiet, though always full. The lawyers here, instead of standing in clumps, chatting nervously and smoking, sit with military precision on the benches along the walls, calculators in hand, stacks of ledger sheets balanced delicately on their knees. They are figuring human failure in dollars and cents.

The lawyers are the only people who painlessly benefit from the business done here. Consider Averil Sweitzer, a plump, pleasant young attorney who averages about 250 divorces a month, earning fees of $75 to $1000 a pop. “It can be the single most efficient act in the courthouse, if you know what you’re doing,” he says.

I sat with Sweitzer through a morning’s docket of uncontested divorces, proceedings that had all the dignity of a cattle auction. One by one the matrimonial losers paraded before the judge, answering well-rehearsed yesses to a short litany of questions. Thwack! went the gavel, and two, ten, twenty years of two persons’ lives were ended. The morning was pretty routine, except for one fellow who had to pay his ex-wife $26,000 in cash and a woman who had resisted divorce until her husband cut down all the trees in their yard and then shot the neighbor’s dog.

But ending a marriage that involves children is considerably trickier. Often the couple makes repeated trips to court. Bob and Jeannie are back this morning because no one can agree on just how much child support Bob owes. Jeannie’s attorney says Bob is $3555 in arrears; Bob, defending himself, says it’s only $2700. Judge Theo Bedard, a prim, officious woman who is the very picture of a divorce judge, says it’s somewhere in between.

Judge Bedard presses Bob for an explanation of his figures, and Bob, who I soon learned could put a lot of lawyers to shame, throws his first curve: the missing $800 or so was paid to Jeannie, but in cash. No check stub, no receipt, no record.

“Did you ever receive such a payment?” asks the judge.

“No,” says Jeannie. And so we’re back to square one. Organ music, please. Is Bob telling the truth or is Jeannie? Will Jeannie and Bob kiss and make up? And how long must Jeannie’s attorney keep the meter running?

A Few Words About Lawyers

The cockeyed worldview of the practicing attorney dominates the courthouse. The lawyers here spend less time arguing the law than making deals. There are guidelines, of course, but they are loose and ever-changing, subject to the whim of the day, the weather, the judge, and what else is on the docket. This system of situational ethics determines the way justice is dispensed at the courthouse. How confusedly or correctly, quickly or slowly, anything works is entirely up to the lawyers.

Mostly things work slowly. The proceedings are a war of attrition in which the key weapon is paper-motions, passes, responses, amendments, codicils, affidavits, transcripts, depositions, charges, restraining orders, verdicts, appeals briefs, requests for probation. A courthouse can rightly be called a paradigm of a democracy, a miniature society of both laws and men. What binds the two together is paper.

Peter Lesser is a bright young lawyer who has what attorneys call a courthouse practice, meaning that he spends the majority of his hours here, either trying cases or working out plea bargains. On a typical morning, I find Lesser doing what most lawyers do on their downtime—schmoozing with the judge. This activity involves flattering, kidding, and shooting the breeze with judges when they’re off the bench, with the hope of building and maintaining good rapport. The goings-on at any courthouse are chummy exercises wherein the prosecutor, the defense attorney, and the judge dispose of business with a smile and a handshake; the adversary relationship described in law school textbooks is hard to find. This is especially true at the Dallas courthouse, where Henry Wade has been district attorney for 33 years. Most of its courtrooms are stocked with judges and defense attorneys who once worked in Wade’s office. The result is camaraderie on all sides and a silent covenant about how things should and shouldn’t be done.

His schmoozing finished, Lesser hurries out into the corridor to find two clients who are facing misdemeanor charges of resisting arrest—something about a row with a security guard in a bar. Lesser thinks the evidence is flimsy; he’d prefer to get rid of the case without a trial, and odds are that he will. The need to relieve the system of a certain number of cases each day supersedes all other priorities, including justice.

This is especially true in the county’s misdemeanor courts, where minor infractions are handled—first DWIs, simple assaults, and the like. Indeed, following a lawyer like Lesser through a morning in misdemeanor courts quickly teaches even the casual observer that this entire body of criminal transgression, filling ten courts with some 40,000 cases a year, is one that nobody really cares about. Defense attorneys just want to settle the cases and get paid; judges just want to collect the fees and fines; prosecutors just want to serve their time and move up to a felony court. The business attended to here seems not only unpleasant but almost trivial.

Lesser hurries to yet another courtroom to settle a DWI case. His client, a young man of about twenty, has been picked up on the charge for the second time. In addition to the loss of license for one year, which is an automatic consequence of conviction, the prosecutor, because of current political pressures, has recommended thirty days in jail and a $300 fine. Lesser thinks that’s steep, particularly since his client will probably lose his job if he loses his license. He talks first to the prosecutor, then to the judge. The key to any plea bargain is to let everybody save face and hope that at some point justice is served. When the deal has been cut, Lesser informs his client: a fine, eight days of jail time, and two years of probation. The youth nods with resignation and, after a brief appearance before the judge, heads to the clerk’s office to pay the fine.

The lethargy typical of most of the courthouse does not extend to the collection of money. In the clerk’s office, typewriters and computers whir, and normally sour-looking clerks perk up at the sight of $100 bills. In 1982 these ten misdemeanor courts collected a total of $6.5 million in fines and fees.

The Paper Chase

Often the wheels of justice don’t even grind slowly; they just spin and spin and spin. On any given day, in any given courtroom, one is less likely to find resolution than postponement and procrastination. To the observer, it seems that the unspoken code of the courthouse is never to resolve what can be put off and never to simplify what can be made more complex.

Consider the matter of Fred* and Eileen* and their four young children. Fred and Eileen became part of the courthouse culture in November 1980, the day a doctor at Children’s Medical Center discovered a small piece of wire lodged in their five-month-old daughter’s ear. A report of suspected child abuse was made to county authorities, who dispatched a welfare caseworker to the home. The caseworker reported that she found the mother hiding in a closet. Subsequent conversations with Fred revealed that Eileen had been acting strangely for some time and that he was afraid to leave the children alone with her. He also said two of the children had become so withdrawn that they had not spoken in school for a year.

The DA’s office filed a “petition affecting the parent-child relationship,” which requested that the children undergo psychological and physical evaluation. The findings were troubling but unspectacular. All four had speech and articulation problems, and two were essentially mute. But there was no clear evidence of physical abuse or neglect. The children remained with their parents with the provision that they be enrolled in special reading and speech therapy programs.

In the meantime, a psychological evaluation of Fred was ordered. The interview revealed that he had been married six times and had been arrested repeatedly for drunk driving. The psychologist also reported a possible acute paranoid state. Eileen, it was discovered, had recently been treated and released from Terrell State Hospital. Still the recommendation was “no continued intervention.”

In August 1981 Fred’s attorney asked to withdraw from the case because Fred wasn’t cooperating with him. Apparently he wasn’t cooperating with anyone. Caseworkers found out that the parents were not taking the children to the recommended speech therapy programs. The DA’s office filed a motion for a writ of attachment and temporary relief, asking that the children be placed in the temporary custody of the state. The judge denied the request but ordered the parents to send the children to the special programs. The state was named temporary managing conservator, but the parents were also named temporary possessory conservators with possession, meaning that the kids were still in the home and that after a year’s worth of motions and hearings and extensive reports, nothing had really happened.

In September the DA’s office filed another motion based on a report that the children were still not attending the special classes. This time the judge ordered that the two youngest children be placed in temporary foster care. In December the DA’s office filed a petition seeking termination of parental rights, requesting permanent managing conservatorship of the children. Over the next six months, more tests were ordered and more hearings were held, but nothing was resolved. In mid-1982 Fred filed a writ of habeas corpus, seeking the release of the two children under foster care.

Finally, in November 1982, the DA’s office demanded a trial. The jury was asked to consider 24 separate issues, although in plain English all it was deciding was whether Fred and Eileen should keep their kids. After three days the jury ruled that the children be turned over to the state; they were placed in foster care and made available for adoption.

Admittedly, child custody is one of the most difficult matters that the system must mediate, but it is sad that it took two years, a handful of lawyers, and thousands of taxpayers’ dollars to get four children into a reasonably healthy environment. The file on Fred and Eileen is six inches thick, though what needed to be decided can be stated in a single sentence. This inertia pervades the courthouse. Not working is the way things work.

In October 1983 a teacher of one of the children reported that his foster mother seemed to be unusually harsh on him, which suggests that Fred and Eileen’s kids may yet again come in contact with the courthouse. And a month later one last bit of paper was added to the accumulation. Fred’s lawyer filed a motion to modify the final judgment, which had identified Fred with an incorrect middle initial. Even when the system finally stops spinning its wheels and moves forward, it never seems to get things quite right.

Randy Kucera’s First Case Continues

“Your honor, I object! May we approach the bench?” Well, it was bound to happen, but Randy Kucera hadn’t wanted it to happen this soon. He has just presented his first piece of evidence in State v. Alvin Eugene Turner, and the defense attorney, a bearded courthouse veteran named Brian Eberstein, is already in his face. Worse, Eberstein seems to be enjoying it.

There is much hushed talking at the bench, during which the jury looks rightly miffed at being left out. Eberstein doesn’t think the hand-drawn map of the intersection that Kucera has tried to introduce is true to scale. It’s a transparent bit of harassment; the drawing’s scale has nothing to do with whether Turner was drunk. But after more talking, Kucera agrees to redraw the map on the courtroom blackboard. He then carefully leads Dorothy Smith through her testimony. All goes smoothly until one of his final questions: “Was there anything that would have made him [Turner] swerve?”

“Objection.”

“Sustained.”

Kucera pauses. He had phrased the question improperly. It called for a conclusion from the witness. It’s another matter of process over results. When, after three more attempts, Kucera finally finds the magical construct “Was there anything in his way?” (to which the witness may respond, since it calls for an observation rather than a conclusion), he elicits the same information he had initially sought. But that’s what courthouses are all about—finding the right process.

Smith’s testimony holds up well on cross-examination. When she steps down, Kucera feels confident he has established that she was the victim of a drunk driver. He next calls Linda Sampson, who heard the collision that day and ran into her front yard. Sampson bolsters Smith’s contention that Turner appeared to be drunk. “He was too intoxicated to be driving,” she says evenly. Kucera stifles a grin. Sometimes witnesses are even better onstage than in rehearsal.

He brings on Lena Trigg, Sampson’s neighbor, who testifies similarly. Now Kucera is ready for his clincher: the testimony of Officer Charles Epperson, the investigating officer in the case. Epperson is as close as Kucera can get to expert testimony. He has investigated 150 or so cases of DWI in his career as a patrolman, and his opinions about Turner’s intoxication and the circumstances of the collision should carry weight with the jury—if Kucera doesn’t blow it, that is.

Fortunately, Epperson is a stunning witness: handsome, articulate, credible. He not only testifies that Turner’s car had to weave to hit Smith’s but he adds that Turner was more verbally abusive than any DWI suspect he had ever dealt with. “He was beyond mad,” says Epperson. And during cross-examination he steadfastly refuses to be baited by defense counsel. At one point the defense attorney says, “Why are you smiling, Officer? Do you find these proceedings humorous?”

“No, sir. I just have a happy, pleasant disposition.”

When Epperson stands down and the court recesses for an hour, Kucera reflects on his case. All in all, he is pleased. But he has the nagging feeling that when the defense puts on its case this afternoon, there will be a surprise. His worry is not assuaged when after the recess Eberstein sidles up to him and says kiddingly, “You better go ahead and dismiss this one and keep the blemish off your record.”

Friday Night at the Jail

What you notice first about the brand-new Dallas County jail is that it has very few bars. Whether this should be considered penological progress depends on whom you talk to. But electronic sliding-glass doors in the place of cold, steel bars definitely give the jail a less ominous feel, as though it were not a jail at all but a hospital or the big atrium lobby of a hotel.

During the shift from 10 p.m. Friday to 5 a.m. Saturday, drunks, petty thieves, brawlers, car thieves, burglars, and more drunks wind up behind the glass. The first wave comes in around eleven, and the intake room fills almost instantly.

“Where you been?” a black intake officer asks a weaving, red-faced young man in overalls and a T-shirt.

“Great American Drink-Off,” he replies with labor.

“You win?”

The bored-looking cop behind the man cackles. The drunk laughs right along. As intake officers like to say, these are the happy drunks—folks who started drinking at happy hour and got picked up driving home down the wrong side of the road, that sort of thing. The intake officer fills out a brief sheet of essential information and asks the arrestee to remove his jewelry, other personal effects, and shoes and socks. Then he shakes the fellow down. As the officer pats around the drunk’s crotch, the man says, “You got twenty minutes, big guy, and it better be good!”

Next to them a younger fellow with acne is being shaken down by another officer. In the same anatomical area, the officer detects a strange bulge. He reaches inside the youth’s jeans and pulls out a small bag filled with a leafy green substance. “This what I think it is?”

“Yeah,” says the youth sullenly. The officers fairly beam at their unexpected good fortune.

One by one the arrestees file through. In nine hours at intake, I see a couple of burglars and a couple of auto thieves, a wife beater and several serious assaulters. But mainly I see drunks—drunks who are here just because they are drunk, drunks who tried to drive, drunks who got into fights, drunks who got a little fuzzy about the concept of other people’s property. A night at a county jail offers striking evidence of the connection between drinking and crime.

About midnight the scene is spruced up a bit by the appearance of twelve ladies of the night who were picked up for loitering and blocking a public roadway. “Say,” says the lady intake officer, turning to me, “these two look like women to you?”

I study the delicate, meticulously made-up faces of two young black women who are, frankly, knockouts. “Yeah, for sure.”

“Okay,” she says, “watch this.” She orders the shorter of the two to take off her wig and jacket. The wig has been hiding close-cropped hair, but that’s in style for women these days. Under the jacket, though, are biceps that are clearly a man’s. “Queers,” says the officer. “Been through here lots of times. The straight hookers hate ’em, but they can’t seem to get rid of ’em.”

After the arrestees are checked in, most are strip-searched and placed in a holding room to await arraignment. In the meantime they may use a phone to arrange bail. Eighty per cent of them will be out of jail within 72 hours. Some, like the three hookers I spotted about 45 minutes later blithely paying their $200 bonds, will be out almost immediately. The county jail, like the rest of the courthouse, is primarily concerned with getting rid of things.

“It’s only one-thirty,” says a hefty prostitute in a miniskirt. “A girl can still get lucky.”

Courthouse Women

The county courthouse is among the last tax-supported bastions of male chauvinism. To be sure, there are more female faces on the bench and in the DA’s office than there were ten years ago. But the majority of the women who work at the courthouse are secretaries and clerks. This is not to say that courthouse women are unimportant. If men make the life-altering decisions, women set the tone. It is the women who keep things moving smoothly by doing their routine, often tedious work, thereby preserving and perpetuating the culture.

Billie Roush is typical of the courthouse woman. Middle-aged and middle class, she approaches her work with precision and grace. She has reached a détente with the male chauvinism that pervades the place; she’s learned to work around and through it. For ten years she has worked in the central jury room and has risen to the position of chief bailiff. On a Monday morning Roush can be found scurrying among five or six hundred sleepy-eyed and confused prospective jurors, answering queries about parking, lunch, and rest rooms. She also fields constant calls for jury panels from the courthouse’s 67 courts. After each call she quickly counts out cards for fifteen or thirty or fifty jurors from the day’s stack and has those people sent to the appropriate court.

The peculiar mathematics of stocking the courthouse with jurors each day has become second nature to Roush. Some 2000 citizens had been summoned for this Monday, on the premise that only about 600 would actually show up. The remainder either requested a postponement, were excused because of age or ailment, or just didn’t appear. Roush also put additional citizens on call; she knows she can always come up with another 25 to 50 prospective jurors if she needs them.

“I like the family atmosphere,” Roush says. “A courthouse is a place where a lot of people work for a long time. The turnover is not that high, and you get to know people. Would I want to do anything else? Well, if my boss ever moved on to something else, I’d like his job.”

One day she probably will have that job. Five years from now, this department may be on a different floor, there may be a different face behind the bench in that courtroom. But on a Monday morning, I’m certain I would find Billie Roush keeping things humming in the central jury room. As her boss, jury director Jess Moore, says, “She’s the glue.”

The Second Episode of Bob and Jeannie

“Your honor,” says Bob, “I can prove that I made those cash payments.” He takes a cassette tape out of his briefcase. “I have a recording of a conversation with Jeannie where she says, ‘I agree with you about the money you paid me.’ ” Jeannie squints at him.

Considerable wrangling ensues over whether the tape can be admitted. Judge Bedard is dry and clinical. “Let’s hear it,” she says. Bob produces a small cassette player and punches it up. The ten-minute taped conversation is inconclusive; Jeannie never clearly admits receiving cash payments. The judge looks peeved. Jeannie looks angry. Bob shuts off the recorder and turns to his last gambit.

“Your honor,” he says, his voice quivering, “I am not a wealthy man. I guess you could say I’m at the mercy of the court.” What follows is a performance that would have put Laurence Olivier to shame. Bob says his job at an air conditioning shop pays only $240 a month. He has already lost his car, and they’re about to foreclose on his house. His new wife just got out of the hospital. Her children need dental work. “I can’t pay all this now,” he concludes, “and if you put me in jail, it’ll just be worse.”

Jeannie and her attorney are not impressed. “I’ve got problems too,” says Jeannie evenly. “My daughter needs dental work too.” And still no one knows how much Bob owes or how he can pay it. Jeannie’s attorney points out that this is the second time Bob has been hauled into court for nonpayment and contempt. Under the circumstances, a stint in jail is in order. If necessary it could be on a work-release program so that he could continue earning money.

Judge Bedard goes fishing for a compromise. Can a payout schedule be arranged? Jeannie’s attorney says there has been one all along. Will Bob agree to have his weekly paycheck garnisheed in a certain amount? “I guess,” says Bob.

“Go to the phone in the back and call your employer right now,” orders Judge Bedard. “See if he’s willing to do it.”

Did it have to take nine hours of attorney time at $150 per and a whole morning of court time to reach such a simple solution?

Later That Friday Night

As dawn approaches, the faces at the jail intake desk become more belligerent. A young Mexican American is brought in on DWI. He glares at the officer when asked to remove his jewelry.

“You speak English?” asks the officer.

“A little.”

“You speak Spanish?”

“A little.”

“Well, give me your best shot. Which one do you speak more of?”

On and on they come, a relentless stream of people for whom Friday night at jail is just part of the weekend celebration. A blond drunk to my left is dragged in screaming, “I’ve answered all the f—ing questions I’m gonna answer!”

A slight fellow with a beard leans unsteadily on a desk. “Ever been in jail before?” the officer asks him.

“I wouldn’t really know unless I asked my lawyer,” he slurs.

To break the monotony, the officers engage in a bit of friendly wagering. One favorite is betting on what certain drunks will “blow” on the Breathalyzer.

“He’s a nineteen. Five bucks.”

“You’re on. He’s a twenty-four if he’s anything.”

“What’d he blow?”

“Ain’t gonna believe it. A twenty-nine. He’s not drunk. He’s dead.”

County jails differ from prisons in that the prisoners they house are technically still innocent. The people locked up here show little resignation or humility. They are furious, and they want their rights. An officer brings in a hysterical young man who is so violent that he must be shackled; he was picked up for beating his wife. “I’m gonna go find another jerk. See ya in about ten,” the arresting officer says brightly. Then there’s a young Mexican American man who was picked up for trying to break into a car; probation papers are found on him. Another angry drunk claims he’s going to sue the county. When asked where he is from, he replies, “I forget.” “Knew you’d trip him up somewhere,” says the arresting officer dryly. There are more dopers, an elderly Vietnamese man who bows at everyone who comes near or speaks to him, a father and son picked up for DWI. “It’s all your damn fault,” the boy keeps saying. No arrestee seems the least bit contrite.

Courthouse Hattie

Hattie Lee Stevens has two gold teeth that match her gold blouse nicely. A statuesque black woman who will confess to 77 years of age, she is as much a fixture at this courthouse as the elevators. But she has no real reason to be here.

Hattie is a courthouse groupie. Officially, she says she works this party or that as a consultant and investigator. But what Hattie really does is watch trials. She has been watching trials for twenty years “professionally,” ten of them in Dallas. Occasionally she works the federal courthouse, but she spends most weekdays in one of the county’s criminal courts.

“Sometimes I watch five a day,” she says. “I’ll help out either side, when it’s right. But I ain’t gonna help no murderers or rapists.”

Hattie’s help generally comes in the form of psychic visions that tell her whether the defendant is guilty and how the trial will come out. “I’ve helped many a young lawyer down here,” she says, flashing that distinctive smile. “But you can’t trust no one in this business, no one.” Hattie says she sometimes travels to other cities and states to watch big trials. She also takes on cause célèbres; she says she is presently working at clearing attorney general Jim Mattox’s name. “I am strictly a criminal courts psychic,” she explains. “I don’t work civil cases.”

Everyone seems to know Hattie. As we sit in the sixth-floor corridor, lawyers, clerks, and judges greet her with a wave and a smile. It’s no wonder: Hattie estimates that she has watched thousands of trials. But like most others who work the system, she has little to say about it qualitatively. “I guess if all these years have taught me anything,” she says, as we stroll to the elevator, “it’s that there ain’t too many of ’em here who didn’t do it.”

“He Just Goes Haywire”

In theory a courthouse is a place that teaches, or at least coerces, people to take responsibility for their actions. But any courthouse does just as much relieving of responsibility. On the second floor of the records building the most heart-wrenching scenes have long occurred each Tuesday and Thursday morning. These are probate courts, but two mornings a week they undertake the county courthouse’s most unpleasant task, shipping the mentally ill and the allegedly mentally ill off to Terrell State Hospital.

Watching commitment proceedings is about as interesting and pleasant as watching someone grind his teeth. Judge Nikki DeShazo calls a name and a case number, and some poor soul is escorted into the courtroom. The people involved may show signs of inner conflict; often a family member will weep for five minutes before and after taking the stand to recommend that a relative be put away.

The first case on the docket is that of a bearded young man who has already been to Terrell once. His mother became concerned about him again after his release, when she discovered that he was living under a highway bridge. After moving back home, he became mercurial and at times violent. “He just goes haywire,” his mother testifies. “He threw some coffee on me, and an ashtray once, too.”

The state’s attorney and the young man’s court-appointed counsel have a mutual objective: to get the man committed as quickly as possible without violating his rights. It is on the latter point that a morning spent in mental illness court can be most unsettling. Judge DeShazo eventually asks the young man if he understands what is going on. “A little bit,” he says. He admits, however, that he does need to “cool off a little bit.” Thwack goes the gavel; he is off to Terrell for ninety days.

And so it goes. The elderly suffering from various forms of dementia. The young suffering from drug-induced psychosis. All kinds of people who just can’t cope. In every case, a relative is asking the state to relieve him of the burden.

The final case this morning is the most poignant. An elderly man is being committed by his wife of sixty years. In recent months, she testifies, he has become increasingly paranoid. “He thinks I’m trying to poison him. He thinks he smells gas all the time. Also, sometimes he wanders off and stands in the middle of the street.”

When the man takes the stand, he claims his wife is “trying to get rid of me. She’s been seen with another man. His name is Jack.” When the man’s commitment is ordered, his wife is teary-eyed. But as she follows him out of the courtroom, there is a trace of relief on her face.

Randy Kucera’s Case Comes to a Close

For all their magisterial posturing and pretense, judges perform some of the most boring chores in the courthouse. All morning they listen to pleas of guilty and intone the same litany of constitutional safeguards to wrongdoers, take applications for revocation of probation or parole, listen to attorneys. They spend the rest of the day urging lawyers and their clients to reach an acceptable compromise; among the more frequently heard words are “whatever you all want to do.”

Judge McCall, like most Texas judges, is a friendly, avuncular sort of man who looks a bit disgruntled that he must listen to State v. Turner. He has an overwhelming docket to move, and trials on such trivial matters can set him back as much as a week. Although the jury trial is considered the zenith of the system, judges discourage the procedure whenever possible because it uses up time, space, and money. While certainly pragmatic, this tendency can make one uneasy about just how justice gets meted out here.

The defense attorney begins his case. “Did you smell anything unusual on Mr. Turner’s breath?” he asks one Cleopatra Sadler.

“I didn’t smell anything unusual,” answers Sadler.

It is pretty much as Randy Kucera expected. Sadler, her husband, and two other friends of Alvin Eugene Turner’s will be called to swear that Turner worked in the yard that day and had only one or two beers, that he didn’t seem drunk at all at the scene of the accident, that his eyes were red that night because of a lifelong medical condition, and that the wreck appeared to be Dorothy Smith’s fault.

The key for Kucera on cross-examination is not so much to accuse the witnesses of lying as to impeach their relative abilities to make judgments about Turner’s state of intoxication. With Sadler this is easy. “Ms. Sadler, what does an intoxicated person look like?”

“They look different than anybody.”

“How?”

“They look sleepy and like they’re about to fall down.”

“Sleepy.” It’s a deft move for the young prosecutor, emphasizing to the jury that her understanding of drunkenness is limited. “How many drunk people have you been around in your life?”

“I haven’t been around too many. . . . I’m a Christian and I don’t drink.”

Kucera doesn’t add anything. She has made his point for him.

Turner’s friend Robert Campbell next testifies that Turner picked him up at his house about midday and they drove back to Turner’s residence to dig a garden with some other friends. Turner went to buy a six-pack of beer. “He didn’t have over two,” Campbell says. Turner returned Campbell to his home later that afternoon. Kucera’s point on cross-examination is simple: “You don’t know where he was after he dropped you off, do you?”

“No.”

The trial takes a short recess, and when the parties return, Kucera’s worst fears are confirmed. Horace Rose, an acquaintance of Turner’s, takes the stand to testify that he saw the wreck that night while driving down Overton and that it appeared to be Smith’s fault.

What to do? Kucera could try to pick Rose’s version apart, but that might be wasted motion. Instead, he again tries to impeach the witness. “Mr. Rose, why didn’t you stop that night?” Rose says it didn’t appear to be a major accident and he was in a hurry. “You didn’t see that front end all smashed in?”

“Yeah.”

“And you wouldn’t call that a major accident?” Kucera turns on the juice. “You didn’t stop, and yet you knew this man and you knew you might be a material witness to an accident?”

At this point defense counsel objects; Kucera has gone too far and argued with the witness. Objection sustained. But the prosecutor wants to make one more point. He asks when Rose and Turner first and last talked about the case. Rose indicates a time lapse of several months, suggesting that Turner hadn’t been too concerned about the accident until it became clear that the case was going to trial.

Now comes the long-awaited testimony of Alvin Turner himself. Turner admits to cursing at various people after the wreck. “Sure I was upset . . . and there was a little foul language,” he says. But he insists that the wreck wasn’t his fault and that two other officers who arrived shortly before Officer Epperson never mentioned DWI to him. He says the half-empty bottle of Canadian whiskey found in the car must have been his son’s. He says he ran back to the car to help Smith.

In cross-examining Turner, Kucera asks him how he would know if he was intoxicated.

“I would if I was. I would lose my sense of balance.”

Kucera hopes the jury didn’t miss that. Turner has just described the way several witnesses said he acted that night. He finishes his cross-examination by asking if Turner turned down a Breathalyzer test.

“Yes,” says Turner, and practically speaking, Randy Kucera has just completed his first trial as a Dallas County prosecutor.

But there is one more tactic he’d like to try. He recalls Officer Epperson.

“Officer, based on your experience as a patrolman, do you have an opinion as to who was at fault in this collision?”

“Objection.”

“Overruled.”

“Clearly the defendant’s vehicle was at fault due to his intoxication,” says Epperson.

“Even if there hadn’t been a wreck, would you have arrested him anyway?”

More objections, which are sustained. Kucera tries the question three or four more times. He’s running a risk now, he really is; too much more of this and he’s going to turn the jurors against him for wasting time. He finally finds the right turn of phrase, and Epperson says flatly, “Operating that vehicle as drunk as he was, he was drunk-driving.”

As Kucera makes his final argument the courtroom is hushed. “DWI is not a game, and I want you to look at your verdict as a message, a message to Alvin Turner that DWI is wrong.”

The jury retires to deliberate, and Kucera looks relieved. While awaiting the knock on the door from the jury, Kucera sits with me and reflects. All in all, he was less nervous than he had thought he would be. “The thing is, you’ve just got to pay attention,” he says. “Keeping track of all the processes is the thing.”

Five, ten minutes pass. Kucera, the defense lawyers, and the bailiff make friendly wagers on when the knock will come. After about twenty minutes, the jury indicates it is ready. Kucera stands up and sighs deeply, just within earshot of the defense lawyer. His adversary turns to him and in that best courthouse tradition says, “Relax, relax.” He then grins, as if to say, “You’ve got it made, kid.”

“We the jury find the defendant guilty, as charged.” Kucera’s assistant slaps him on the back, and Kucera breaks into his first sincere grin in three days. By God, he’s done it. But what does it mean?

Within the hour, Judge McCall will assess Turner’s punishment at sixty days in jail, to be probated over two years, a $300 fine, and one hundred hours of community service. The principals file out of the courtroom, each wearing an odd expression of emptiness. Randy Kucera and his assistant walk toward the elevator; they’ve got another case to prepare. The jurors straggle down the hall, some looking dazed, others peeved. Though something has certainly been accomplished, no one looks particularly fulfilled.

*Names marked by an asterisk have been changed to protect the subject’s privacy.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Dallas