This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The standard case against George Bush can be conveyed by invoking two annoying neologisms, wimp and preppie: Bush is thought to be too much the second banana and too upper-class to be president. Neither of these is exactly right. In fact, they obscure the real worry that we ought to have about Bush as president.

Bush is not a wimp; if anything, he is a compulsive adventure seeker. The drama of his life, to judge from the account in his recently published autobiography, Looking Forward, consists of his repeatedly deciding to reject the safe, standard course and to do something unusual and dangerous. He risked his life and became a Navy pilot right out of high school. He moved to Texas after college instead of taking a job in New York. He gave up a safe seat in Congress and a place on the Ways and Means Committee to run for the Senate in 1970. He turned down the chance to be the U.S. ambassador in London so that he could run a small diplomatic outpost in Peking. His decision to enter the 1980 presidential race was a wild gamble, given that he had no real stature as a national political figure. Up until the vice presidency, Bush had the restless career of a lone wolf; lurking behind his famous résumé is a career in government devoid of sustained experience at running something.

The reason that Bush seems wimpy is because any two-term vice president to a strong president inevitably will look like a wimp, especially if he is loyal. Even Lyndon Johnson, who for good or ill almost defined nonwimpdom, seemed ineffectual and sycophantic while he was vice president. He was relegated to serving on interagency task forces and to being made fun of by the president’s aides. Relatively minor officials in the Kennedy administration tell stories of Johnson’s calling them on the slightest pretext and talking for hours, simply because he didn’t have anything to do. Bush’s quiescence as vice president in no way means he would be a do-nothing president—probably, given his self-image as an unconventional risk taker, he would have the opposite fault.

Bush is a preppie, it’s true; what he isn’t is an aristocrat. His background is entirely different from that of the real upper-class candidate for president, Pete du Pont. Bush comes from the upper-managerial class, a race of solid, affluent (and old-fashioned Republican) citizens who run businesses, go to church, and do civic work but who don’t build mansions, amass art collections, or rule high society; responsibility, not money, limns their lives. Bush’s roots in Greenwich, Connecticut, the rich New York suburb where he grew up, run pretty shallow. His mother is from St. Louis, and his father, who ended his business career on Wall Street but began it at Simmons Hardware, grew up in Columbus, Ohio. Rockefellers and Kennedys are bred to power, Bushes to duty; Bush might be a character in a novel by James Gould Cozzens, not Louis Auchincloss. While Bush doesn’t have Jesse Jackson’s personal knowledge of poverty and oppression, neither does he represent an extreme unconnectedness to real life and its problems.

The hallmark of Bush’s class is an obsession with a certain kind of behavior: modest, conscientious, loyal, and honest. A Henry Ford doesn’t really need those qualities to succeed in the world, but a George Bush does. The problem with Bush is that he learned his lessons about how to comport himself almost too well. He seems to be a splendid person, but his vision is based almost entirely on his ideas about personal conduct rather than about society, and that, not wimpiness or preppiness, is his biggest flaw as a potential president.

In Looking Foward, Bush describes his (and his father’s) attraction to politics as a feeling of obligation to serve, not a desire to govern with particular ends in mind. His father, Prescott Bush, Sr., ran for the U.S. Senate from Connecticut because “he felt he had a debt to pay,” not because he had any passion for politics. In fact, Bush says, “the subject of politics seldom came up at family gatherings.” Bush made his first race, for the Senate in 1964, because he and his wife wanted “to put something back into a society that had given us so much.” This is probably disingenuous, but the hidden impulse that Bush doesn’t fully admit seems to be an attraction to the excitement of politics, not the urge to carry out an agenda. He speaks vaguely of having concerns about “the way things were going” and “our children’s future.” In one scene of Looking Forward, when the wily old governor of Ohio, James Rhodes, forcefully tells Bush that politics boils down to “jobs, jobs, jobs,” what is striking is the lack of any similar core belief in Bush.

What Bush has to offer in government is not a program but his integrity. He is called on to serve when the president needs someone to project a squeaky-clean image, not to make policy—as the head of the Republican National Committee during Watergate or of the CIA after the Church Committee hearings. He sees the challenge of each job as proving that it can be done honorably. Aside from a conviction that the Chinese are motivated primarily by their fear of the Russians, the lessons his experience has taught him are personal, not political: Don’t stand in the way of an employee who wants to move on to another job; be a good listener; don’t criticize the boss publicly; fire someone in person, not by memo or proxy. In Looking Forward, Henry Kissinger tells Bush that it doesn’t matter whether a foreign government likes an ambassador. Naturally, Bush disagrees—it is the essence of his way of thinking to put personal respect ahead of geopolitics.

There was a time when the notion that good men from the private sector would inevitably produce good government lay at the heart of the Republican party. In the days when the party’s soul was in the small towns of the Northeast and the Midwest and in the suburbs of the older industrial cities, Republicans thought Democratic politics was dirty, in part because Democratic politicians regarded government as a career rather than as a form of service. Oddly enough, presidential candidates who have embodied the Republican beau ideal of the nonideological businessman-public servant—Wendell Willkie, for instance—have always lost. Of the Republicans elected president in the last half-century, Dwight Eisenhower, Richard Nixon, and Gerald Ford were all career government employees, and Ronald Reagan emerged from a political movement with well-defined views about what government should do. Bush would be the first Republican president since the New Deal who has actually met a payroll and spent most of his government career on the distinguished-appointee side of Washington.

By now, of course, the Republican heartland has moved—to the South and the West and the right. Bush’s life history and rhetoric make it clear that he is intellectually well aware of this shift. But it has had little evident effect on his soul. Most presidents have been deeply affected by the social changes that have played across their lives. John F. Kennedy was very much a product of World War II and of the ethnic ascendancy of the Irish in America. Lyndon Johnson was shaped by the Hill Country and the New Deal. The civil rights movement left a deep mark on Jimmy Carter. Reagan drew social lessons from almost everything that ever happened to him, and on the whole, his way of thinking grew out of his experience as a participant in the great migration of small-town Midwesterners to Southern California. Bush’s compass points have to do with his childhood and adolescence, with private events instead of public ones. It always comes down to “the way I was brought up.”

Presidents (except for Woodrow Wilson) are not political science professors. They almost never come to office with the specifics of their policies set in their minds. If Bush doesn’t have an obvious agenda now, it shouldn’t be held against him too much—neither did Franklin Roosevelt at this stage. More than we like to admit, a president is made by his in-box or rather by the interaction of his in-box with his mind, his character, and his political and administrative skills. If Bush is elected president, he will have to do something about the federal deficit, a task that requires enormous political skill and a sophisticated feeling for which claims on the federal treasury are justified and which aren’t. In other words, the deficit is nearly the perfect example of a problem that the personal integrity of the president won’t be of much help in solving. You can’t fix it simply by doing the right thing; you have to know in your bones what the government needs to keep doing and what it doesn’t, and Bush hasn’t given us any sense that he does know this. We don’t need to worry about his turning out to be corrupt or lazy or dissembling. We ought to worry about whether he has it in him to be a statesman.

Contributing editor Nicholas Lemann is a national correspondent for the Atlantic.

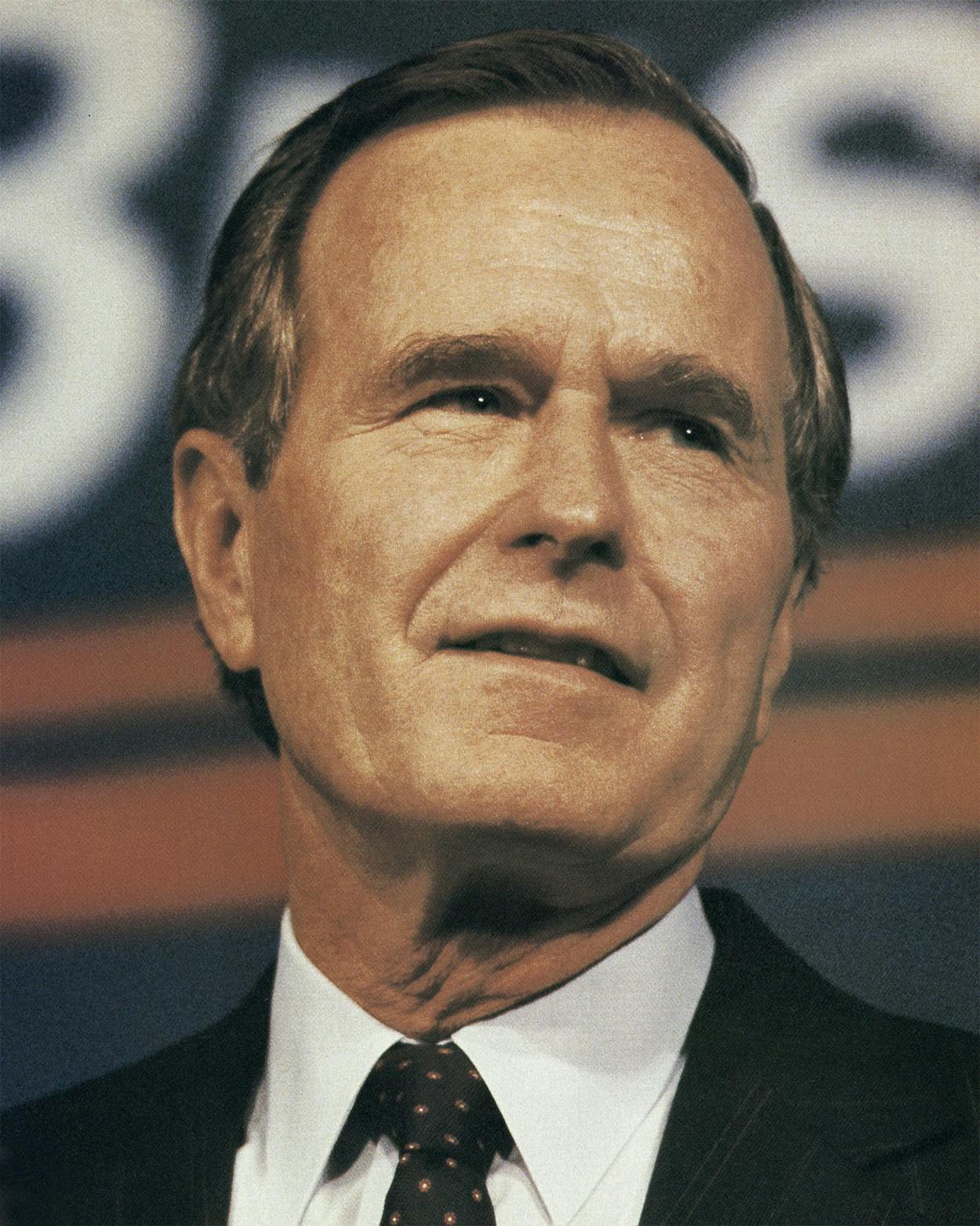

Should This Man Be President?

In praise of résumés; a Yankee’s grievance.

John Ehrlichman

Novelist and former member of the White House staff

Yes: In the summer of 1970, Texas congressman George Bush, a candidate for the U.S. Senate, went to San Clemente to talk to Richard Nixon. Bush and other oil-state congressmen and senators had come to urge the president to support retention of the oil depletion allowance in the tax code. During the meeting Bush stood out; he was well prepared and articulate. Afterward the president agreed to go along with the depletion allowance and insisted that Bush be permitted to announce the victory. Nixon also resolved to find things for George Bush to do within his own administration, in case George was defeated in the difficult Texas Senate race.

Bush’s appointment as ambassador to the United Nations had its origins in that San Clemente meeting. Nixon wanted a strong spokesman at the U.N. who had friends in Congress and was a capable politician. Moreover, Bush was willing to be the president’s ambassador, not a vassal of the State Department. And so George’s long résumé began.

The criticism that Bush is a résumé candidate misses the point. He has been asked to serve in so many positions because he has the qualities essential for success in politics. And they were first noticed by someone who held the very office to which Bush now aspires.

Joseph Nocera

Contributing editor, Newsweek

No: Did you read the story in the Wall Street Journal a few months ago about how you could “rent” George Bush’s legal residence in Houston? The alleged residence turns out to be a suite in the Houstonian, which the vice president frequents maybe ten times a year. Bush “lives” in Texas, he says, so he can vote there. Sure. The lack of a state income tax is pure coincidence.

The place where George Bush really lives, at least when he’s not in Washington, is Maine. If I may speak for my fellow New Englanders, we find this a little on the embarrassing side. It’s not that we’re against evading taxes, necessarily. It’s just that in New England there is a proper way to do this sort of thing. You don’t rent a hotel room—how cheesy! You move to no-tax New Hampshire and then you live there—putting up with, among other things, miserable weather, lousy services, and a hopelessly bankrupt utility company. And you don’t whine about it either, which is another thing that makes us cringe every time we see our “native son” on the tube. Whether he’s fighting over microphones with Ronald Reagan or shouting at Dan Rather, George Bush can’t seem to open his mouth without whining. The way we look at it, that’s the dominant side of his personality coming to the fore. The Texas side. Texas has gotten very good at whining the last few years.

So here’s the thing, Texas: If you want to claim George Bush on the basis of ten nights a year in a hotel room, hey, don’t let us get in your way. We’re a modest, stoic, taciturn bunch up here. Our idea of the perfect New Englander is J. D. Salinger, not George Bush. When the dust finally settles and Bush suddenly needs a job (as he surely will), we have a suggestion. He can become a lobbyist for a major oil company. That way he can whine for a living. And we won’t have to listen.

Two views of toughness.

Larry L. King

Author and playwright

No: George Bush as rugged Texan is pretty funny, given that he can’t even make a fist. Next time you see him on TV talking tough to the Democrats or Dan Rather, observe his technique: George wraps his thumb outside his knuckles, which guarantees (a) an inability to generate power and (b) a broken thumb should he accidentally hit anything.

I can’t help giggling when I read that Vice President Bush “worked in the Texas oil fields.” I worked in the oil fields; George founded Zapata Petroleum. I imagine while I was hanging out in Odessa beer joints with roughnecks who occasionally negotiated with the unreasonable after carefully tucking in their thumbs, George was dining at the Midland Petroleum Club because the Yale Club in Midland didn’t have a dining room. For that matter, neither did my Texas Tech Club. We met over nachos and beer at Ray’s Rendezvous Inn.

None of this means I would make a better president than George Bush, you understand, but he’s gonna have to learn to make a fist before I can see him as a tough-talking Texan. George and I do have a couple of things in common: We live but five blocks apart in Washington’s richest and only Republican precinct, and each of us has been away from our true home for a long, long time. Mine is Midland-Odessa; his is Kennebunkport.

Chase Untermeyer

Assistant secretary of the Navy and former aide to Bush

Yes: On March 30, 1981, Bush was in Fort Worth aboard Air Force Two when the Secret Service flashed a message to Bush’s lead agent on the plane: “There has been an attempt on the president.” As the plane headed back to Washington, the lead agent and the vice president’s military aide asked Bush to take the Marine helicopter directly from Andrews Air Force Base to the South Lawn of the White House rather than to the grounds of the Naval Observatory, where the vice-presidential mansion is located. The White House, they said, is the most secure place in the city. Bush rejected their advice. He would not land on the South Lawn, he said, because only the president lands there.

His decision was politically astute as well as principled. Not on that day or on any of those to follow would Bush attempt to portray himself as president. Reagan’s longtime staffers would have been outraged had Bush tried to advance himself, but I-am-in-control-here bravado is not his style.

A photograph taken on that day shows the high-level mob scene that awaited Bush at the White House. The ultrasensitive Situation Room, which is about the size of a suburban dining room, was bursting with every grandee in the executive branch. When the vice president arrived, the tumult ceased and the straphangers cleared out. In short, George Bush was in control.

Too often leadership and toughness are cartooned as loud, brash, strutting, and demanding. George Bush is none of these, and critics have made much of that. But to Bush, toughness is not how you act; it’s what you are. In a genuine crisis he showed that coolness and calm thinking are always preferable to show and bluster.

Bush Meets the Pens

The unmaking of a presidential candidate, in exclusive caricatures by six leading political cartoonists.

Don Wright, Miami News

“Start with a beaked nose, jutting jaw, forced smile, and—no offense here—rodent eyes, very close together. Put them together, and they look like George Bush.”

Ben Sargent, Austin American-Statesman

“Some people are harder to capture, but Bush came right out of my pencil. Whether he really is a wimp is immaterial. He’s so defensive and testy about it.”

Tony Auth, Philadelphia Inquirer

“I looked at a tape of Bush being interviewed by David Frost and watched his face in action. He has a delightful mouth. It’s twisted in a very revealing way.”

Jell MacNelly, Chicago Tribune

“He has half an acre of forehead and looks very patrician. This caricature is subject to change. Jimmy Carter started shrinking. Reagan got older and goofier.”

Pal Oliphant, King Features Syndicate

“I’m voting for Bush—he’s easier to caricature than Dole. Everybody goes with their own PAC, and mine wants somebody who will be good material for four years.”

Doug Marlette, Atlanta Constitution

“George Bush claiming to be a Texan reminds me of a white man trying to act like a brother. It’s not obnoxious. Just kind of pathetic. Manure comes to mind.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Books

- TM Classics

- George H.W. Bush