Governor Greg Abbott made frequent pilgrimages to McAllen in 2020, so it did not surprise anyone that on January 8 of this year he flew down to the border city to headline a Hispanic Leadership Summit. After remarks from conservative leaders in the Rio Grande Valley such as McAllen mayor Javier Villalobos, Abbott took the stage to officially launch his reelection campaign in a speech punctuated by twin blasts of confetti. That Abbott would end a Hispanic leadership event with an announcement of his own leadership intentions was no coincidence. He made clear that day that he planned on winning the Hispanic vote in Texas in November.

Last week Abbott declared an early win toward that goal. Though no Republicans ran against any Democrats in the Texas primary election last Tuesday, by Wednesday morning Abbott was already hailing his party’s success: “Texas Republicans see big gains in Rio Grande Valley based on turnout in Tuesday’s primary election. . . . The #RGV will be RED this November!” he tweeted.

Abbott’s focus on South Texas is easy to understand. In 2020, then-president Donald Trump massively outperformed expectations in the borderlands. Now the largely Hispanic and historically deep blue region could predict the near-term political future of Texas. If the area continues to trend Republican, Texas will no longer look like a “purpling” state.

Given the stakes, everyone is searching for data that can predict how Hispanics across South Texas will vote in November. In the wake of last Tuesday’s primary, that meant obsessing over primary data and how many Democrats versus Republicans had come out to vote in the March 1 election. Democrats were quick to counter Abbott: even with GOP gains, Democratic primary voters still outnumbered Republican ones three to one in most districts. Mike Barreto, a Democratic pollster, also pointed out how easy it is to spin the numbers: he compared turnout data from last Tuesday with the 2020 general election to paint a picture of Republican support cratering. “BREAKING: GOP SEES MAJOR DROP IN LATINO SUPPORT 20-to-22 IN RIO GRANDE VALLEY,” he tweeted, in jest.

Everyone’s spin was infected by the same problem: using primary data as a crystal ball to predict the results of a general election is about as reliable as . . . well, looking into a crystal ball. It’s only going to tell you what you want to see.

Let’s start with a basic fact: primary turnout so rarely predicts the results of general elections that pollsters don’t find it a useful metric. Michael McDonald, a political science professor at the University of Florida and an expert on turnout, told me that, at times, one can read some “tea leaves” about voter enthusiasm during presidential primaries. But he remains cautious about drawing any conclusions from that data, and particularly from down-ballot numbers: “There is less [predictive] value in low turnout and low-visibility state and congressional primaries.”

That’s true nationwide, but it’s even more true in South Texas, where thousands of Republicans have shown up to vote in the primaries as Democrats throughout the past few decades. Why? Democrats have controlled so many counties in Texas, for entire generations, that many local races don’t have any Republicans on the ballot. Even when conservatives do run—and they often do—they have tended to run with a D next to their name. (In Zapata, a small county to the south of Laredo, local Democratic organizers told me it’s an open secret that multiple officials elected as Democrats voted for Trump.)

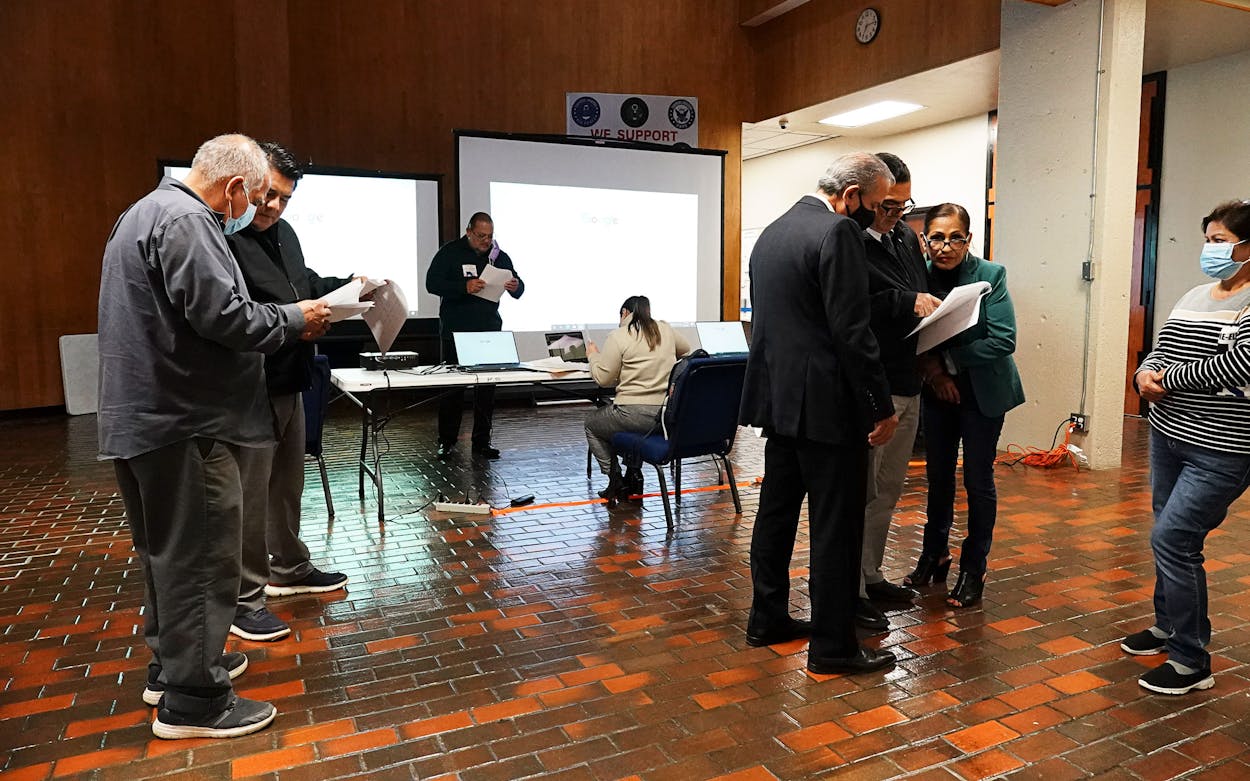

“I’m a Republican but I take a Democrat ballot,” said Juan Ramirez, a business owner in Laredo whom I met on Election Day outside the Guerra Centre, a strip mall and voting precinct. He said he wouldn’t be able to vote in various elections if he chose to fill out a Republican ballot. “It’s not fair, but that’s how the system works.”

To understand how many people make the same sort of decision as Ramirez, consider Starr County, the westernmost county in the Rio Grande Valley and home to Rio Grande City. In the 2018 primaries, 15 voters filled out a Republican primary ballot. Not a typo—only 15! In comparison, more than 6,700 people filled out a Democrat ballot. But eight months later, in the general election, Starr sent in 3,217 votes for Abbott (who lost the county handily to onetime Dallas County sheriff Lupe Valdez) atop the ticket, and 2,443 votes for Senator Ted Cruz (who got crushed by El Paso congressman Beto O’Rourke in the county).

With that caveat out of the way, let’s look at the numbers for this year. Republicans have been spiking the football in celebration of how many more voters cast ballots in the 2022 GOP primary than in the 2018 one. Republican turnout in Starr County, for instance, increased by 7,260 percent. That improvement looks truly astronomical—until you remember that, in 2018, only 15 people voted in the Republican primary, against 1,098 this year. Republicans also saw huge percentage gains over 2018 turnout across the rest of the RGV—more than 100 percent in Hidalgo, Willacy, and Cameron counties.

Meanwhile, there are signs that Democrats’ enthusiasm is not where it was in 2018, when the midterms gave the party its first chance to repudiate the polarizing presidency of Trump. Last week, Democratic turnout in many counties in South Texas decreased from the 2018 midterms. In Starr, for instance, it was down almost 50 percent. There could be many reasons for this: Democrats had fewer meaningful races to vote in than they did in 2018, and the incumbent party often sees less voter enthusiasm during midterms than in general elections. President Joe Biden’s popularity numbers are also not great. But one Democratic county chair in South Texas, who asked to remain anonymous in order to share internal party conversations, confided to me that younger Democratic leaders were “despairing over the abysmal low vote.”

Does that mean Democrats are truly in a bad position? Depends on what magic you pull with the data. In Starr, for instance, Democratic primary voters still outnumbered Republican voters by almost three to one. That was true across South Texas counties: Republican turnout massively improved when compared with 2018—but it was still dwarfed by Democratic turnout.

And if you compare turnout numbers from November 2020 (instead of the 2018 midterms) with last week’s election, as some taking victory laps for the Dems have done, things look fantastic for the party. Across the Rio Grande Valley, for instance, Republican turnout cratered by this metric. In Hidalgo County, home of McAllen, the Republican share of the vote dropped from around 47 percent in November 2020 to 28.7 percent in March 2022. That said, it’s basically meaningless to compare these numbers: of course more Republicans showed up to vote in the most consequential presidential election of this century than in the midterms last week. That’s always the way it’s going to go.

So, what can primary turnout numbers tell us? Republican voters are beginning to get organized in South Texas—for the first time in generations. In Zapata County, for example, which didn’t even have a Republican apparatus prior to 2020 but where Trump shockingly won, local conservatives are now officially organized. Republicans continue to get in formation across the region, where multiple conservatives are mounting serious bids for congressional seats and one right-wing super PAC, Project Red Texas, has paid the filing fees for many candidates running for local offices, including justice of the peace. Most important, those candidates are actually running as Republicans now.

These are meaningful changes, and no one can deny that they represent a substantial GOP accomplishment in South Texas. But even though Republicans have vastly improved their position in the race for South Texas, they might still be trailing well behind Democrats, who have been lapping them for decades.

Looking into the crystal ball here will only turn us cross-eyed. For now, all we can read are tweets and tea leaves.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Greg Abbott