This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

This summer Lydia Aguilar-Bryan and Joseph Bryan solved a medical puzzle that had long stumped scientists around the world. After a decade of painstaking lab work at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, the husband-and-wife team discovered how the body regulates the secretion of insulin. The key was a protein found in pancreas cells that governs the process. After isolating the protein, the Bryans identified the gene that creates it, and then they showed how mutations in that gene cause a disease known as familial hyperinsulinism, which is essentially the inverse of diabetes. Hyperinsulinism occurs when a person produces too much insulin, the hormone that directs muscle cells and fat cells to mop up excess blood sugar. The disease causes abnormally low blood sugar levels and can be especially dangerous to infants, whose brains need glucose to develop properly. Thanks to the Bryans’ work, there may soon be a prenatal test for hyperinsulinism and, down the road, a genetic remedy.

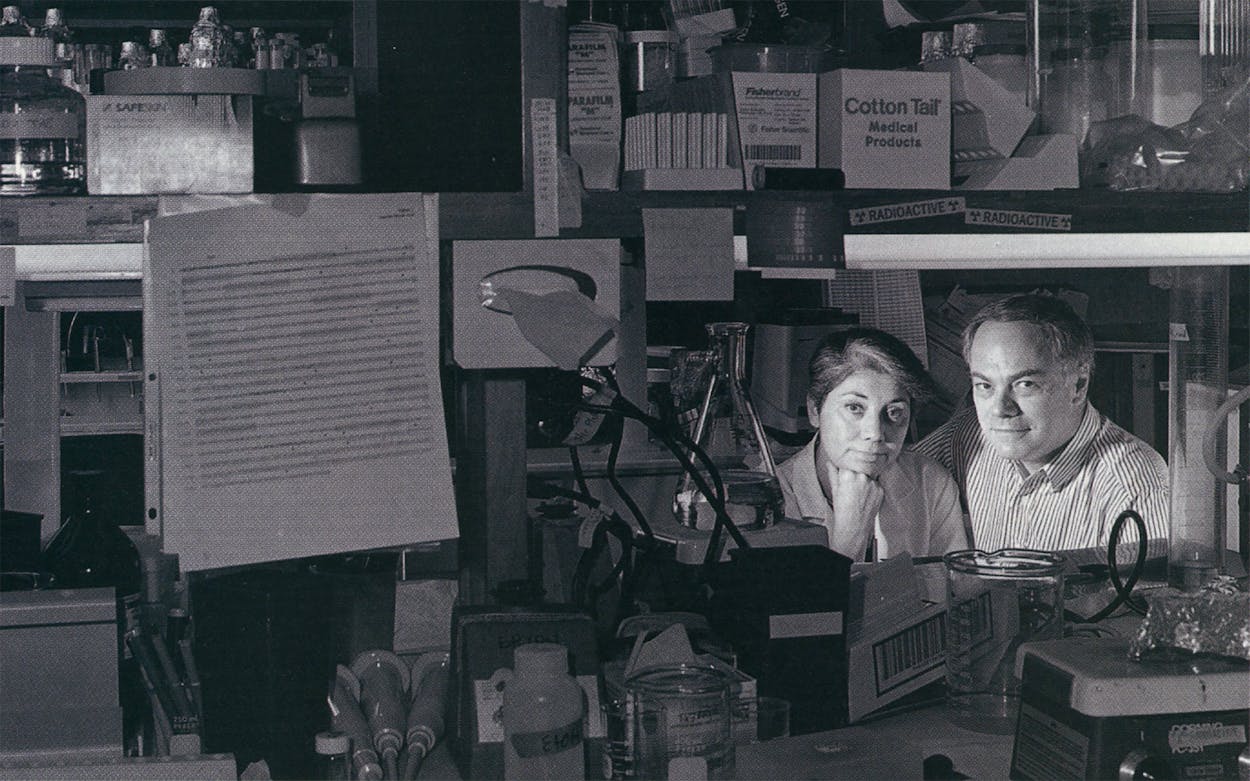

They prevailed out of sheer doggedness. When they started out, they were vying with several other research teams, but over time everybody else abandoned the chase. “It was such a difficult problem that they all gave up,” says Joseph. But the Bryans’ success also owes much to their complementary personalities. Lydia, who is 44, has a wide-open face, dark hair with a sophisticated silver streak, and a warm, down-to-earth manner. Joseph, who is 54, has arching eyebrows that give his face an elfin look and is more of an egghead. “I think of the patients,” Lydia says, “and he thinks of the molecules.”

The patients Lydia was thinking about when she began her research were suffering from diabetes, not hyperinsulinism. People with diabetes have unusually high blood sugar levels—either because their bodies don’t produce enough insulin or because they have become resistant to it—and that can lead to poor circulation, blindness, and even fatal comas. The disease can be regulated to a degree by avoiding sugary, starchy, and fatty foods, injecting insulin, or taking drugs that prompt the body to produce more of its own insulin. Lydia was particularly interested in diabetes because it strikes people of Mexican descent in unusually high numbers. Growing up in Mexico City, she watched a grandmother and one of her uncles die from the disease. Later, as a graduate student at the University of Texas, she studied the phenomenon of diabetes in Starr County, a heavily Mexican American area on the border. Several minority groups develop diabetes at atypically high rates, and the disease afflicts many Mexican Americans, partly because close-knit communities concentrate the gene pool and can cause recessive genes to emerge, but also because of the high-starch, high-fat diet in the United States. Studies show that more than half of the residents over age 35 in Starr County either have diabetes or have close relatives who do.

Shortly after she began her fieldwork in Starr County, Lydia met Joseph, who had recently joined Baylor College of Medicine’s cell biology department after several years at the University of Pennsylvania. A romance flourished, but then Lydia returned to Mexico to work. In 1985, however, after much of Mexico City was leveled by a powerful earthquake, Joseph abandoned his lab and flew there to make sure she was all right, and they were married within a year. Lydia soon accepted a research post in Baylor’s endocrinology department, and that was when she began to study the cellular processes behind the secretion of insulin. After she consulted her husband, he gradually became absorbed in the project.

From the outset the Bryans zeroed in on beta cells, which are tiny factories that produce insulin. They were particularly curious about one protein in the beta cell’s membrane because they believed it functioned as a switch, turning the cell on and off. Other proteins had recently been shown to play similar roles: By opening and closing a hole in a cell’s wall, they controlled the flow of substances that trigger the cell to perform its assigned function.

The specific protein that intrigued the Bryans was a potassium channel. They suspected that the protein told the beta cell when to produce insulin, but nobody had been able to confirm this, because nobody had been able to isolate the potassium channel and unravel the secret of its structure. Twice, respected scientists published articles claiming they had the answer, only to be proven wrong.

A protein is built of a string of amino acids, like a necklace made of beads, and one of the Bryans’ primary goals was to name the linear sequence of amino acids making up their potassium channel. But isolating the protein was tricky, as one beta cell contains several thousand types of proteins. The Bryans adopted the plodding detective habits of traditional biochemistry: They fished for the protein using a drug as bait. They chose sulfonylurea, a drug believed to act by grabbing tightly to a potassium channel. (It makes beta cells produce additional insulin and is often used as a treatment for diabetes.) The first step was to grow large quantities of beta cells in plastic bottles filled with nutrients. It would take weeks to grow one batch. Then they would smash up the cells with a glass plunger and use a centrifuge to separate the membranes from the rest of the bits. To the membranes they would add a detergent to dissolve the fat lipids that hold the membranes together, freeing up the proteins. Finally, they would mix in a radioactive version of the drug, which allowed them to trace their protein when the mixture was placed on x-ray film. “It was like putting a flashlight on the protein,” Joseph says.

It took the Bryans four years to find the right protein. One time they were sure they’d found it, only to discover they had mistakenly isolated an impostor. “It was a trial-and-error proposition,” Joseph recalls. “You would grow thirty bottles’ worth of cells and try something. Then you would either say, ‘Hurray! That was a good step!’ or, ‘No, that ain’t gonna work.’ ”

Once they had isolated the protein, the Bryans took a sample to technicians at a sequencing lab, who told them what the first amino acids in its structure were. The Bryans later discovered that the entire thing was made up of 1,582 amino acids, but because of technological limitations, a sequencing lab could identify only the first 25 or so. It didn’t matter. Even a partial understanding of their protein was enough to locate the gene, thanks to the close correlation in their structures: Genes are made up of building blocks called nucleotides, and the order of nucleotides in a gene corresponds to the order of amino acids in its protein. Armed with the initial sequence of amino acids, they began to hunt for the gene that creates the potassium channel.

The right gene, of course, was a recipe for the entire protein. After the Bryans found the gene, they used it to make a copy of the protein. The results were astonishing: The protein didn’t look anything like it was supposed to—it didn’t resemble other potassium channels, which explained why it had been so hard to identify. Instead, it looked like ATP-binding proteins, which had recently been shown to cause cystic fibrosis and other serious diseases when they aren’t working properly. “It was a complete surprise,” says Joseph.

After figuring out how the protein was constructed, the Bryans wanted to see if irregular potassium channels—ones that didn’t open and close at the right time—were a cause of diseases such as diabetes. But when they pinpointed the location of their gene within the 48 chromosomes, it fell exactly where another scientist had predicted the gene for familial hyperinsulinism would be. “We hadn’t thought we were going after the hyperinsulinism gene—we didn’t have the foggiest idea,” says Joseph. “But at that stage we suddenly realized that there was no reason why we couldn’t explain familial hyperinsulinism.”

In 1994 the Bryans teamed up with a group of doctors from M. D. Anderson Cancer Center who had been studying families with hyperinsulinism and hunted for any abnormalities in the genes that had been culled from the family members. Together they discovered that extremely subtle mutations in the Bryans’ gene—1 wrong nucleotide out of 70,000 or more in the whole gene—were causing familial hyperinsulinism. Because the variation was so small, it took six months to discover. Joseph pulls out a piece of film from a sequencing lab. “You see this sequence, which is C-C-G-G?” he asks, using the geneticist’s shorthand for various nucleotides. “Here it’s C-C-A-G.”

Now Lydia is contacting researchers who have genetic profiles of families with diabetes—including families in the Valley—to see if mutations in their gene also play a role in causing that disease. The Bryans know that diabetes is probably caused by several faulty genes, but they hope their work will help illuminate its origins too. “I’m looking at populations that have higher frequencies of diabetes,” says Lydia, “so I have Pima Indians from Arizona, who have the highest prevalence of the disease in the world, and I have Mexican Americans and African Americans. I already have samples of their blood in my freezer.”

- More About:

- Health

- TM Classics

- Medicine

- Waco